Gaia spacecraft reveals 'goldmine' of over 500,000 undiscovered stars

The European Space Agency's Gaia telescope revealed half a million newfound stars, and detailed the orbits of over 150,000 asteroids.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

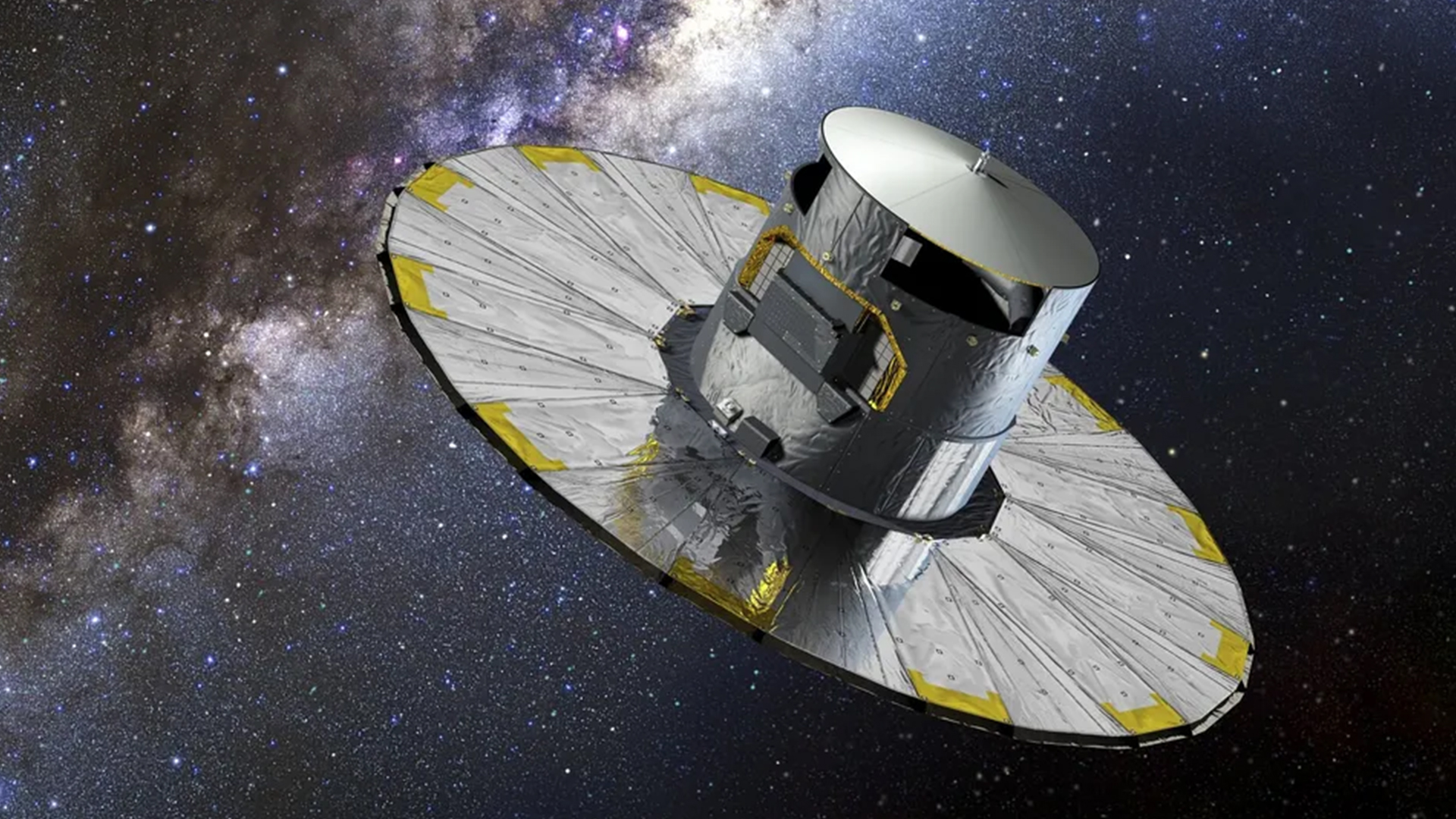

The Gaia mission has revealed a "goldmine" of new information on cosmic objects as it continues to create the most comprehensive stellar catalog ever compiled.

The new release, known as Gaia's focused product release (FPR), contains over half a million new faint stars, more than 380 new gravitationally lensed quasars and the positions of over 150,000 solar system asteroids.

Containing data on 1.8 billion stars, the comprehensive map of the Milky Way galaxy and its cosmic backyard being created by Gaia will allow scientists to continue to dig deep into our cosmic history. The new release fills in some important gaps in that map as it forms.

According to Gaia's operators, the European Space Agency (ESA), the new data provides exciting and unexpected science and findings that go far beyond what the space telescope was initially designed to discover.

The new trove of research builds upon the third Data Release (DR3) from Gaia published in June 2022. Though comprehensive, DR3 contained gaps in the sky not yet mapped by the space telescope and overlooked some faint stars that didn't shine as bright as their surrounding stellar companions.

Particular examples of this are globular clusters, which are some of the oldest objects in the universe with densely clustered cores of bright stars that can overwhelm telescopes attempting to study them.

More than filling in unexplored regions in Gaia's cosmic map

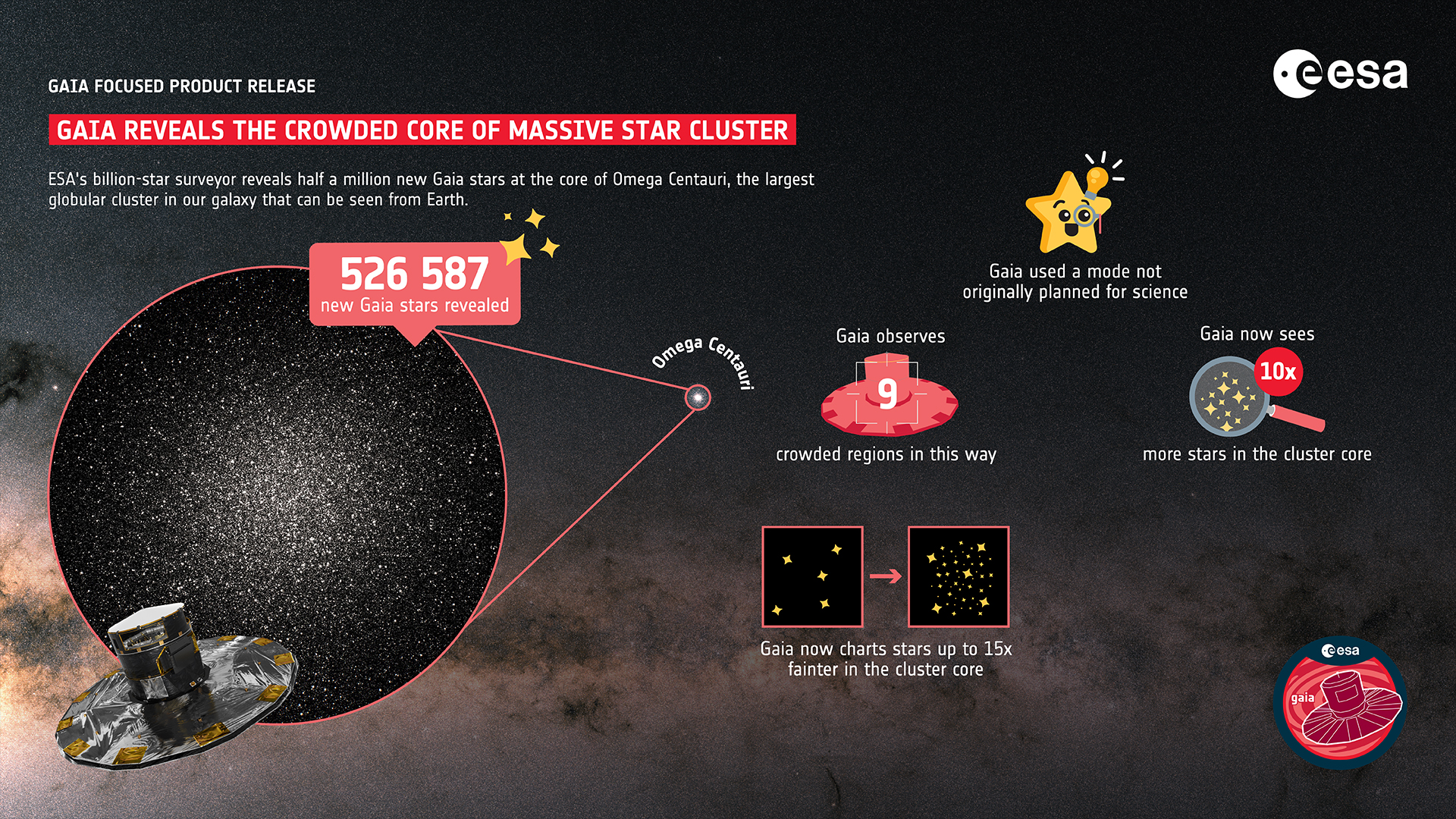

Part of the new release from the star surveyor space telescope focused on the Milky Way's most massive globular star cluster, Omega Centauri, which contains around 10 million stars — making its core the most crowded region of space the telescope has studied thus far.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To patch these gaps, ESA astronomers focused Gaia on Omega Centauri, which, at just around 15,800 light-years away, is relatively close to Earth and can be used as a proxy for the study of other clusters of this type.

"In Omega Centauri, we discovered over half a million new stars Gaia hadn't seen before — from just one cluster!" research lead author and member of the Gaia collaboration Katja Weingrill said in a statement.

Instead of focusing on single stars within the cluster, something Gaia specializes in, the space telescope observed Omega Centauri with a special mode that allows Gaia to look at a wider patch of sky around the core of the globular cluster each time it came into view. Thus, the new observations also helped test this special mode and Gaia's instruments.

"We didn't expect to ever use it for science, which makes this result even more exciting," Weingrill added.

Though the new data has helped fill in some unexplored regions in Gaia's 3D map of the Milky Way, it is of interest to scientists in itself, helping better model the Omega Centauri globular cluster.

"Our data allowed us to detect stars that are too close together to be properly measured in Gaia's regular pipeline," research co-author and Gaia Collaboration member Alexey Mints added. "With the new data, we can study the cluster's structure, how the constituent stars are distributed, how they're moving, and more, creating a complete large-scale map of Omega Centauri. It's using Gaia to its full potential — we've deployed this amazing cosmic tool at maximum power."

In this regard, the new data release of the FPR is just a taster of what is to come in Gaia Data Release 4 (DR4), with the space telescope currently exploring a further eight regions of the Milky Way in a similar fashion to how it investigated Omega Centauri. As a result, by studying cosmic building blocks like Omega Centauri, DR4 could help reveal details about our galaxy, such as its true age, the precise location of its center and if it has collided with other galaxies throughout its history.

Gaia as a gravitational lens hunter

Even though it wasn't designed to study the universe on a wider scale, the FPR releases from Gaia show it could be uncovering things that are vital to understanding the cosmos as a whole, such as its evolution and its precise age.

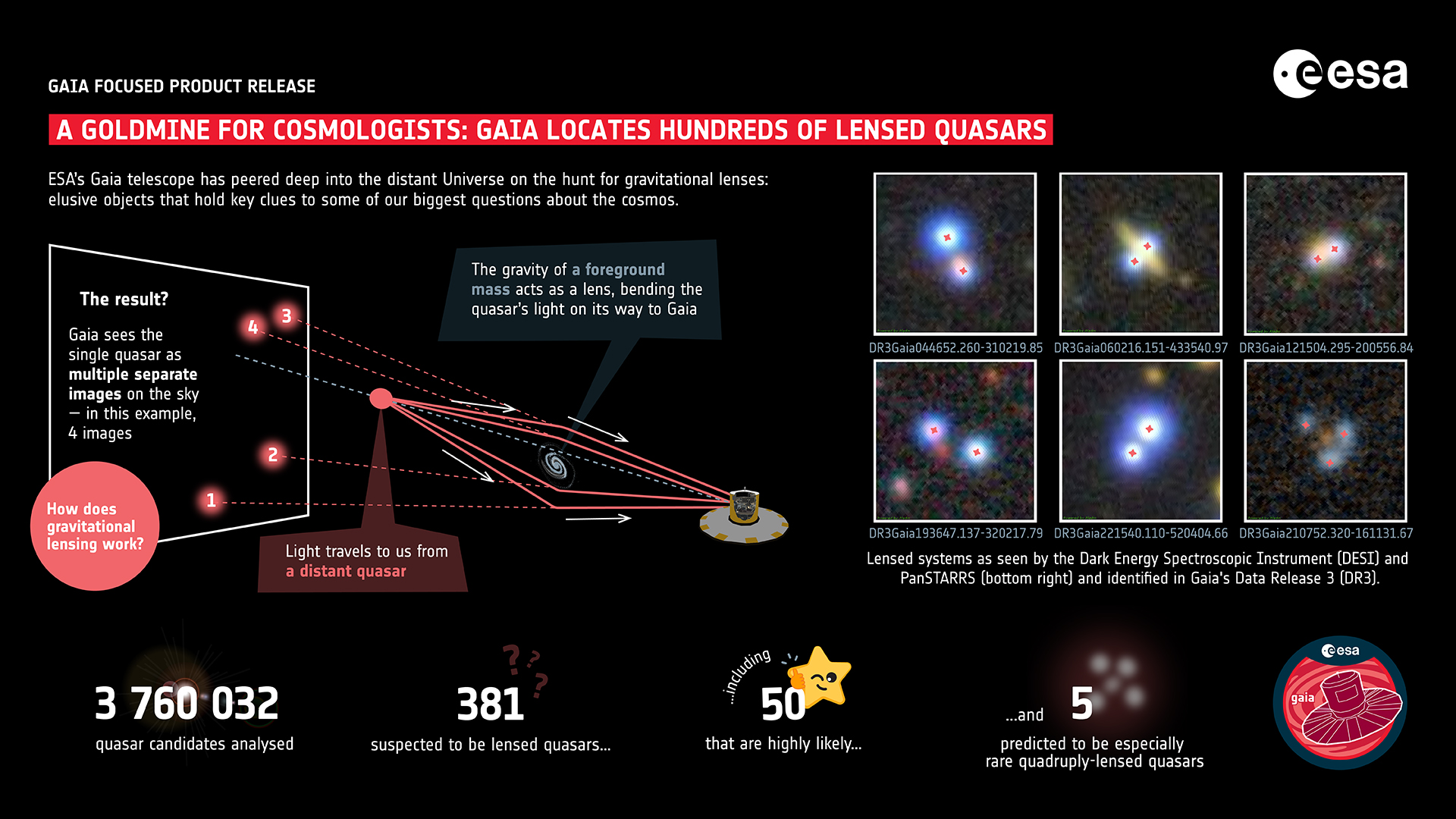

One of the ways Gaia could have an impact on cosmology is by finding what astronomers call gravitational lenses, objects of great density like star clusters that can be used to amplify light from distant background sources like ancient galaxies.

This works thanks to an effect predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity, which suggests that objects of mass "warp" the very fabric of spacetime; the greater the mass, the more extreme the warping is. When a warping object lies between Earth and a distant source, light from that distant source passes the intermediate object and is 'bent' on its way towards us. The amount of deflection depends on how close the light's path comes to the mass source. As a result, light from the same source arrives at Earth at different times and a single object can appear at multiple points in the same image.

This effect can amplify that distant source, allowing objects that would usually be too distant and faint to be seen. The James Webb Space Telescope is currently using this phenomenon to great effect to observe some of the universe's oldest galaxies. Gaia can assist in this by finding more gravitationally lensed objects — particularly quasars, the active hearts of galaxies powered by feeding black holes. Spotting lensed quasars isn't easy because the repeated images caused by gravitational lensing can often cluster together, making a single object appear smeared in images and leading to it being misidentified.

"Gaia is a real lens-seeker. Thanks to Gaia, we've found that some of the objects we see aren't simply stars, even though they look like them," research co-author and Gaia collaboration member Christine Ducourant said. "They're actually really distant lensed quasars — extremely bright, energetic galactic cores powered by black holes.

"We now present 381 solid candidates for lensed quasars, including 50 that we deem highly likely: A goldmine for cosmologists and the largest set of candidates ever released at once."

These candidates were selected from a list of possible quasar candidates, some of which were included in DR3, with five of the lensed objects appearing to be rare formations called "Einstein crosses." These occur when light from a single object appears at multiple places in the same image from the shape of a cross. In 2021, Gaia spotted 12 of these Einstein crosses.

"The great thing about Gaia is that it looks everywhere, so we can find lenses without needing to know where to look," research co-author Gaia collaboration member Laurent Galluccio said. "With this data release, Gaia is the first mission to achieve an all-sky survey of gravitational lenses at high resolution."

This demonstrates how Gaia could team up with the ESA's dark matter and dark energy detective Euclid, launched in July 2023, to help investigate these mysterious aspects of the universe that comprise an estimated 95% of its content. The new releases from Gaia also show the space telescope also has utility much closer to home.

Tracking asteroids, red giants, and more with Gaia

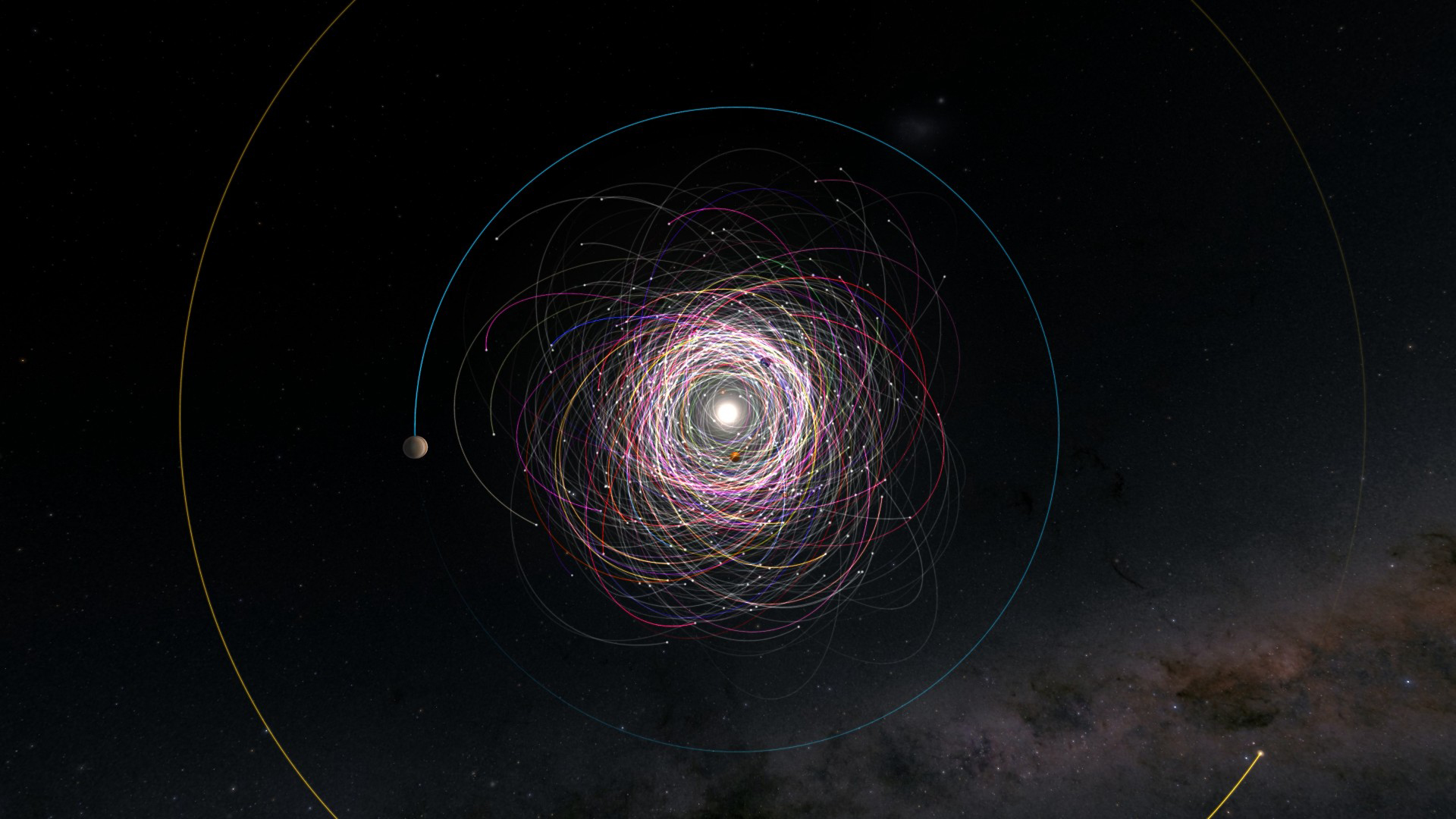

Part of the new Gaia releases show details of 156,823 of the asteroids around Earth that were identified in DR3, better pinpointing their locations and constraining their orbits with 20 times more precision than previous observations.

The ESA space telescope did this by observing the space rocks for almost twice as long as it had previously. The ESA predicts that the forthcoming Gaia data dump DR4 will double the number of asteroids seen by the space telescope as well as increasing the number of solar system bodies observed by Gaia by including comets and even satellites around Earth.

The new Gaia releases also include observations of the dynamics of over 10,000 binary red giant stars, making this the largest collection of such stellar objects ever collated, and signals from gas and dust that drift between stars in the disk of the Milky Way.

"Although its key focus is as a star surveyor, Gaia is exploring everything from the rocky bodies of the solar system to multiply imaged quasars lying billions of light-years away, far beyond the edges of the Milky Way," ESA Gaia project scientist Timo Prusti said. "The mission is providing a truly unique insight into the Universe and the objects within it, and we're really making the most of its broad, all-sky perspective on the skies around us."

The FPR from Gaia takes the form of five papers published on Tuesday, Oct. 10.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus