Does alien life need a planet to survive? Scientists propose intriguing possibility

While such organisms may or may not exist in the universe, the research has important implications for future human endeavors in space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

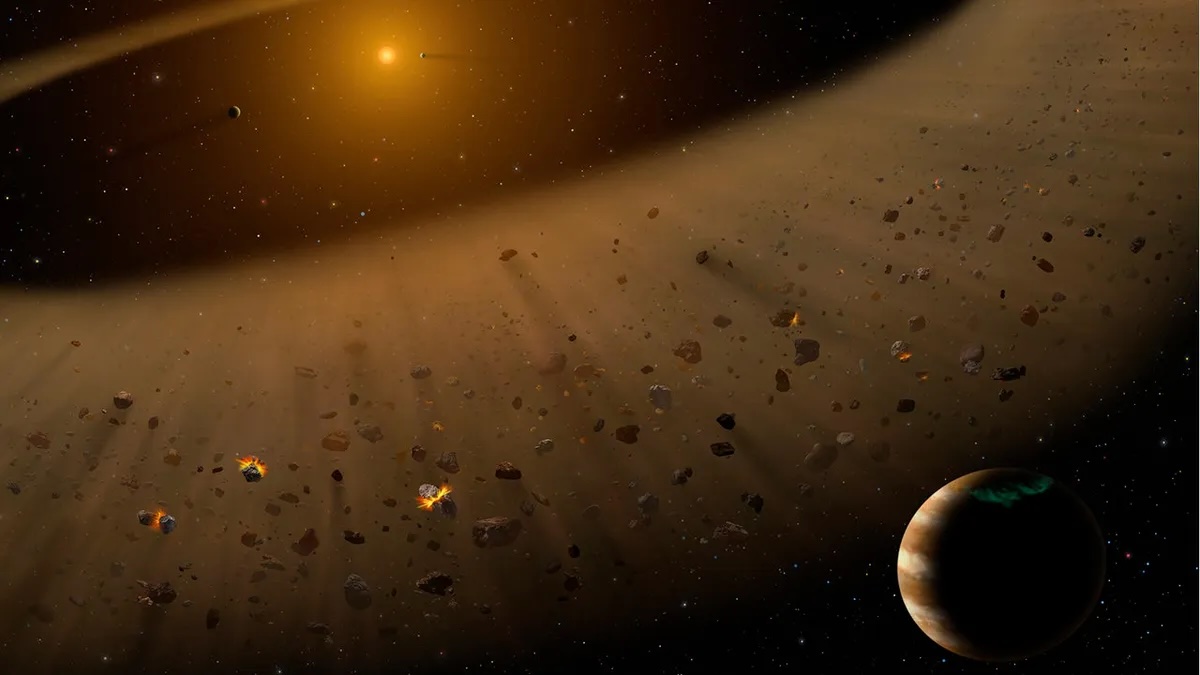

What if we dropped the "terrestrial" from "extraterrestrial"? Scientists recently explored the intriguing possibility that alien life may not need a planet to support itself.

At first glance, planets seem like the ideal locations to find life. After all, the only known place life is known to exist is Earth's surface. And Earth is pretty nice. Our planet has a deep gravitational well that keeps everything in place and a thick atmosphere that keeps surface temperatures in the right ranges to maintain liquid water. We have an abundance of elements like carbon and oxygen to form the building blocks of biological organisms. And we have plenty of sunlight beaming at us, providing an essentially limitless source of free energy.

It's from this basic setup that we organize our searches for life elsewhere in the universe. Sure, there might be exotic environments or crazy chemistries involved, but we still assume that life exists on planets because planets are so naturally suited to life as we know it.

In a recent pre-paper accepted for publication in the journal Astrobiology, researchers challenge this basic assumption by asking if it's possible to construct an environment that allows life to thrive without a planet.

Related: If alien life exists on Europa, we may find it in hydrothermal vents

This idea isn't as crazy as it sounds. In fact, we already have an example of creatures living in space without a planet: the astronauts aboard the International Space Station. Those astronauts require tremendous amounts of Earth-based resources to be constantly shuttled to them, but humans are incredibly complex creatures.

Perhaps simpler organisms could manage it on their own. At least one known organism, the tiny water-dwelling tardigrades, are able to survive in the vacuum of space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Any community of organisms in space needs to tackle several challenges. First, it needs to maintain an interior pressure against the vacuum of space. So a space-based colony would need to form a membrane or shell. Thankfully, this isn't that big of a deal; it's the same pressure difference as that between the surface of water and a depth of about 30 feet (10 meters). Many organisms, both microscopic and macroscopic, can handle these differences with ease.

The next challenge is to maintain a warm enough temperature for liquid water. Earth achieves this through the atmosphere's greenhouse effect, which won't be an option for a smaller biological space colony. The authors point to existing organisms, like the Saharan silver ant (Cataglyphis bombycina), that can regulate their internal temperatures by varying which wavelengths of light they absorb and which they reflect — in essence, creating a greenhouse effect without an atmosphere. So the outer membrane of a free-floating colony of organisms would have to achieve the same selective abilities.

Next, they would have to overcome the loss of lightweight elements. Planets maintain their elements through the sheer force of gravity, but an organic colony would struggle with this. Even optimistically, a colony would lose lightweight elements over the course of tens of thousands of years, so it would have to find ways to replenish itself.

Lastly, the biological colony would have to be positioned within the habitable zone of its star, to access as much sunlight as possible. As for other resources, like carbon or oxygen, the colony would have to start with a steady supply, like an asteroid, and then transition to a closed-loop recycling system among its various components to sustain itself over the long term.

Putting this all together, the researchers paint the portrait of an organism, or colony of organisms, floating freely in space. This structure could be up to 330 feet (100m) across, and it would be contained by a thin, hard, transparent shell. This shell would stabilize its interior water to the right pressure and temperature and allow it to maintain a greenhouse effect.

While such organisms may or may not exist in the universe, the research has important implications for future human endeavors in space. Whereas we currently construct habitats with metal and supply our stations with air, food and water transported from Earth, future habitats may use bioengineered materials to create self-sustaining ecosystems.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus