Astronomers find bizarre 'Cosmic Grapes' galaxy in the early universe. Here's why that's a big deal.

A distant galaxy appears to have more than a dozen tightly packed star-forming clumps arranged like a bunch of grapes — far more than astronomers thought possible in a galaxy from the early universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A distant galaxy appears to have more than a dozen tightly packed star-forming clumps arranged like a bunch of grapes — far more than astronomers thought possible in a galaxy from the early universe.

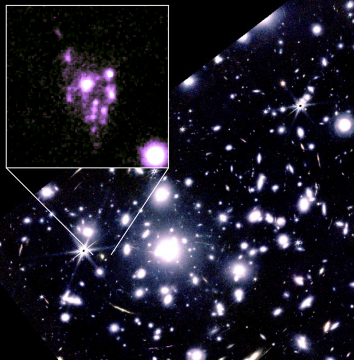

The galaxy, nicknamed "Cosmic Grapes," is believed to have formed just 930 million years after the Big Bang. A new study has revealed that the galaxy has at least 15 massive star-forming clumps in its rotating disk, forming what appears to be a bunch of bright purple grapes in space.

Using NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers discovered the galaxy through a technique known as gravitational lensing, in which a foreground galaxy — in this case, an object known as RXCJ0600-2007 — serves as a magnifying glass for more distant objects.

"This object is known as one of the most strongly gravitationally lensed distant galaxies ever discovered," study lead author Seiji Fujimoto, said in a statement from the University of Texas at Austin's (UT Austin) McDonald Observatory.

"Thanks to this powerful natural magnification, combined with observations from some of the world's most advanced telescopes, we had a unique opportunity to study the internal structure of a distant galaxy at unprecedented sensitivity and resolution," added Fujimoto, who started the research while at UT Austin but is now at the University of Toronto.

The researchers collected more than 100 hours of telescope observations to study the primordial Cosmic Grapes galaxy. Earlier Hubble Space Telescope images of the object suggested a smooth, rotating disk, but the powerful resolution of ALMA and JWST revealed something juicier — the most detailed view yet of the galaxy's inner structure and massive clumps of dense gas primed for star formation.

Related: 'Time machine' reveals hidden structures in the universe's first galaxies

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our observations reveal that some early galaxies' young starlight is dominated by several massive, dense, compact clumps rather than one smooth distribution of stars," study co-author Mike Boylan-Kolchin, an astronomy professor at UT Austin, said in the same statement.

The discovery reshapes our understanding of early galaxy growth by revealing the first clear connection between a galaxy's small internal structures — in this case, massive star-forming clumps — and its overall rotation, hinting that many seemingly smooth galaxies observed before may actually be filled with similar hidden clumps.

Their findings were published Aug. 7 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus