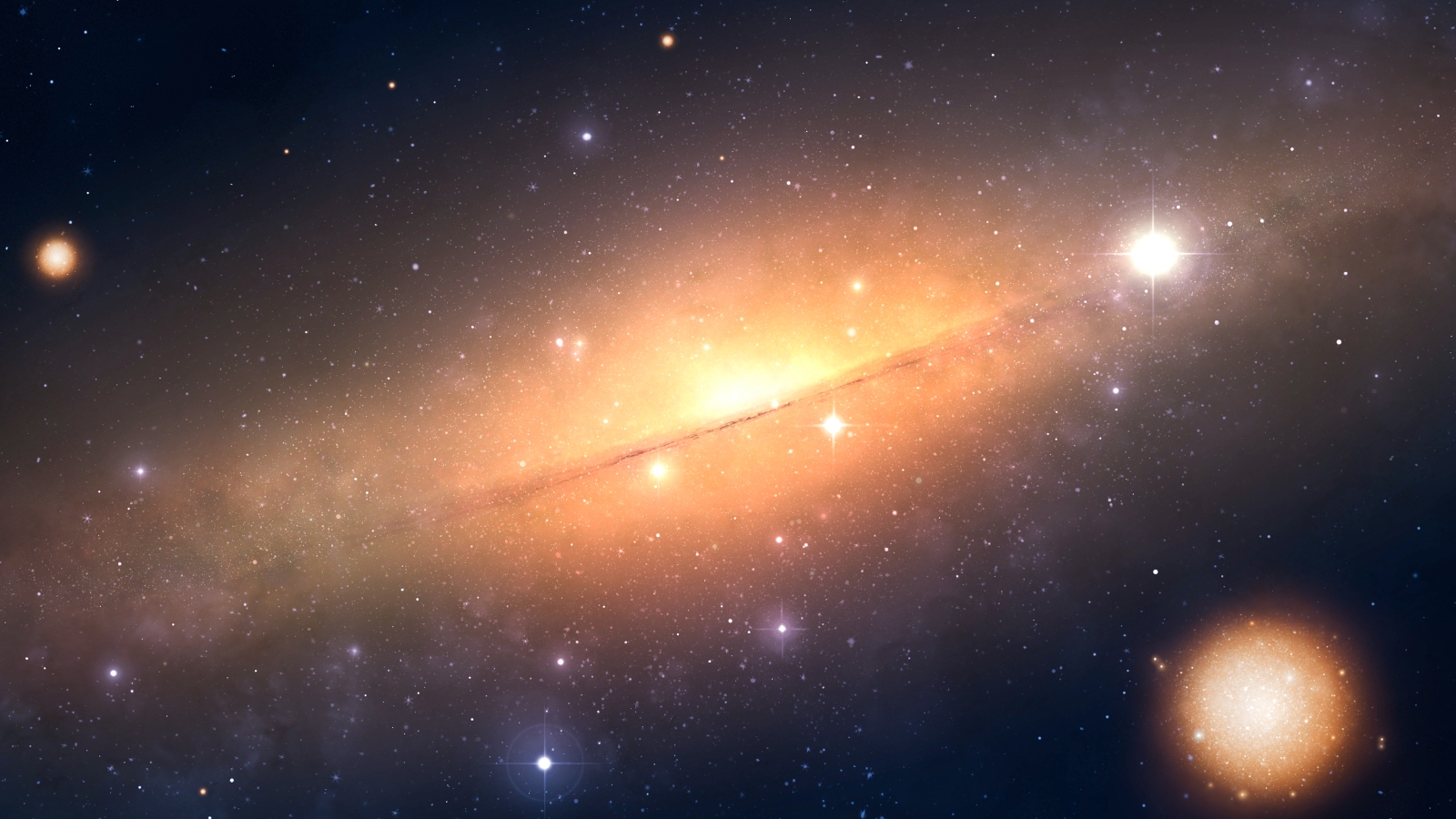

Some of the oldest stars in the universe found hiding near the Milky Way's edge — and they may not be alone

Astronomers reanalyzed the chemical composition of three stars in the Milky Way's halo and found that they are between 12 and 13 billion years old. They may have also been stolen from other galaxies.

Three alien stars circling the Milky Way could be some of the oldest ever found in the universe, a new study reveals. The ancient celestial objects may have been among the first to form after the Big Bang and were likely stolen by our galaxy during gravitational tugs-of-war billions of years ago.

In the study, published May 14 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers reanalyzed three previously observed stars each located around 30,000 light-years from Earth in the Milky Way's halo — a massive cloud of stars that orbit beyond our galaxy's main galactic disk. The basic chemical composition of these stars suggests they are all between 12 and 13 billion years old, making them almost as old as the universe itself, which formed around 13.8 billion years ago.

The trio's respective trajectories through the Milky Way also hint that these stars did not originate in our galaxy but were instead stolen from the periphery of some of the universe's oldest galaxies as the Milky Way brushed past them billions of years ago.

The ancient balls of gas, which researchers have dubbed Small Accreted Stellar System (SASS) stars, are "part of our cosmic family tree," study senior author Anna Frebel, a stellar astrophysicist at MIT, said in a statement.

Normally, stars this old can only be studied by spying on galaxies from the other side of the known universe or by reverse-engineering ancient stars from their descendants. However, the discovery of ancient stars on our cosmic doorstep gives scientists a rare opportunity to study them directly — and researchers are now confident there are more stars like these toward our galaxy's edge.

Related: The James Webb telescope may have found some of the very 1st stars in the universe

The new discovery came about from an MIT class taught by Frebel. Students were encouraged to look through historical data collected by Frebel using the Magellan-Clay Telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile to analyze the chemical composition of stars.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This revealed the stellar trio, which each had an unusually low abundance of heavy metals such as iron, strontium and barium in its atmosphere. For example, one of the stars had around 10,000 times less iron than the sun.

These heavy metals are forged over eons in the heart of stars, and are also found in the exteriors of younger stars, which suck up ingredients that were dispersed by exploding dead stars. The fact that this trio has few heavy metals, means they were formed before most other stars had exploded.

The stars' compositions hinted that they did not originate in the Milky Way. But to confirm this, the students traced the orbital trajectories of the three stars and found that they all had a retrograde motion, meaning they are circling our galaxy's supermassive black hole in the opposite direction from a majority of the other stars.

"The only way you can have stars going the wrong way from the rest of the gang is if you threw them in the wrong way," Frebel said, meaning that these stars were likely ripped from other galaxies by the Milky Way.

Based on the stars' compositions, researchers also believe that each star was ripped from a different galaxy.

In a brief follow-up exercise, Frebel identified another 65 retrograde stars with similarly simple compositions. These stars will now be studied further to determine if they are also SASS stars.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus