'Ridiculously smooth': James Webb telescope spies unusual pancake-like disk around nearby star Vega — and scientists can't explain it

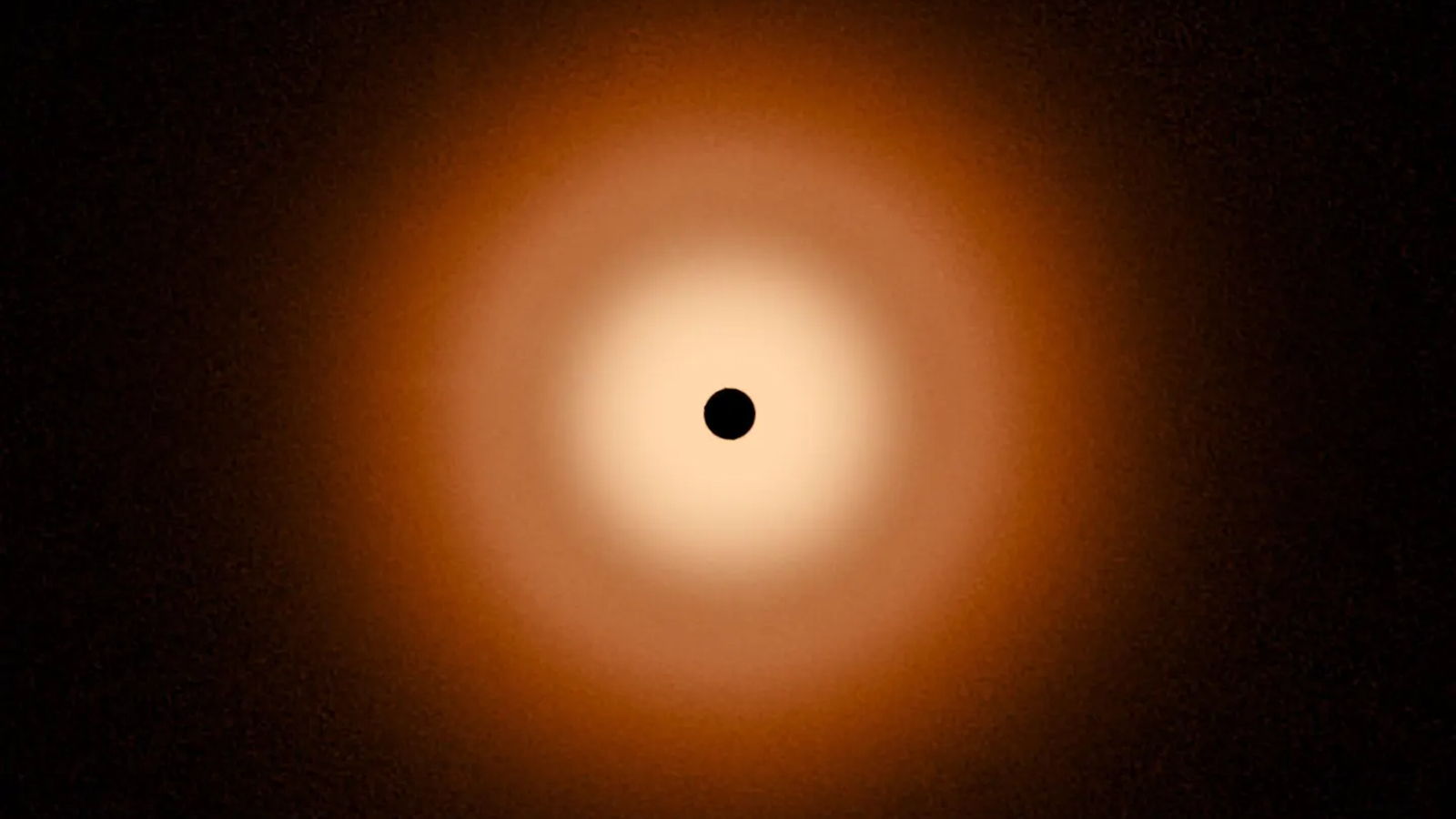

The nearby bright star Vega is surrounded by a surprisingly smooth, 100 billion-mile-wide disk of cosmic dust, confirming that it is not surrounded by any exoplanets, JWST images reveal. And scientists cannot explain its lack of alien worlds.

A nearby star is surrounded by an eerily perfect, "pancake-like" disk of cosmic debris that is unlike anything seen before, new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) images reveal. The surprisingly smooth disk hints that no exoplanets have formed around the star, named Vega, and researchers have no idea why.

The findings could upend our understanding of how alien worlds form.

Vega is a blue-tinged star that's around twice as massive as the sun and located around 25 light-years from Earth. Due to its fast spin, close proximity to Earth and the fact that its magnetic pole is pointed right at us, Vega appears very bright in the night sky: It is the fifth-brightest star visible from Earth to the naked eye. It is also part of the famous "Summer Triangle" of stars, which appears at the start of summer in the Northern Hemisphere.

Besides being a prominent sight in the night sky, Vega was depicted as the home star of an advanced alien civilization in the 1997 sci-fi film "Contact," based on the 1985 Carl Sagan novel of the same name.

Over the past 20 years, astronomers have been studying a massive, 100 billion-mile-wide (161 billion kilometers) circumstellar disk of dust and gas surrounding Vega, similar to the protoplanetary disk that birthed the planets in the solar system around 4.5 billion years ago, soon after the sun was born.

Vega is around half a billion years old, which means it is plenty old enough to support worlds of its own. However, recent observations have hinted that there are no noticeable holes in the disk, suggesting that no exoplanets have formed around the superbright star.

Related: 42 jaw-dropping James Webb Space Telescope images

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a new study, uploaded to the preprint server arXiv on Nov. 1, researchers turned to JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument to peer at this disk. The resulting photos provide the clearest-ever image of Vega's dusty disk and show that it "looks almost as smooth as a pancake, with no signs of planets," the researchers wrote in a statement. (The study has been accepted for future publication in The Astrophysical Journal.)

"The Vega disk is smooth, ridiculously smooth," study co-author Andras Gáspár, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, said in the statement. "It's a mysterious system because it's unlike other circumstellar disks we've looked at."

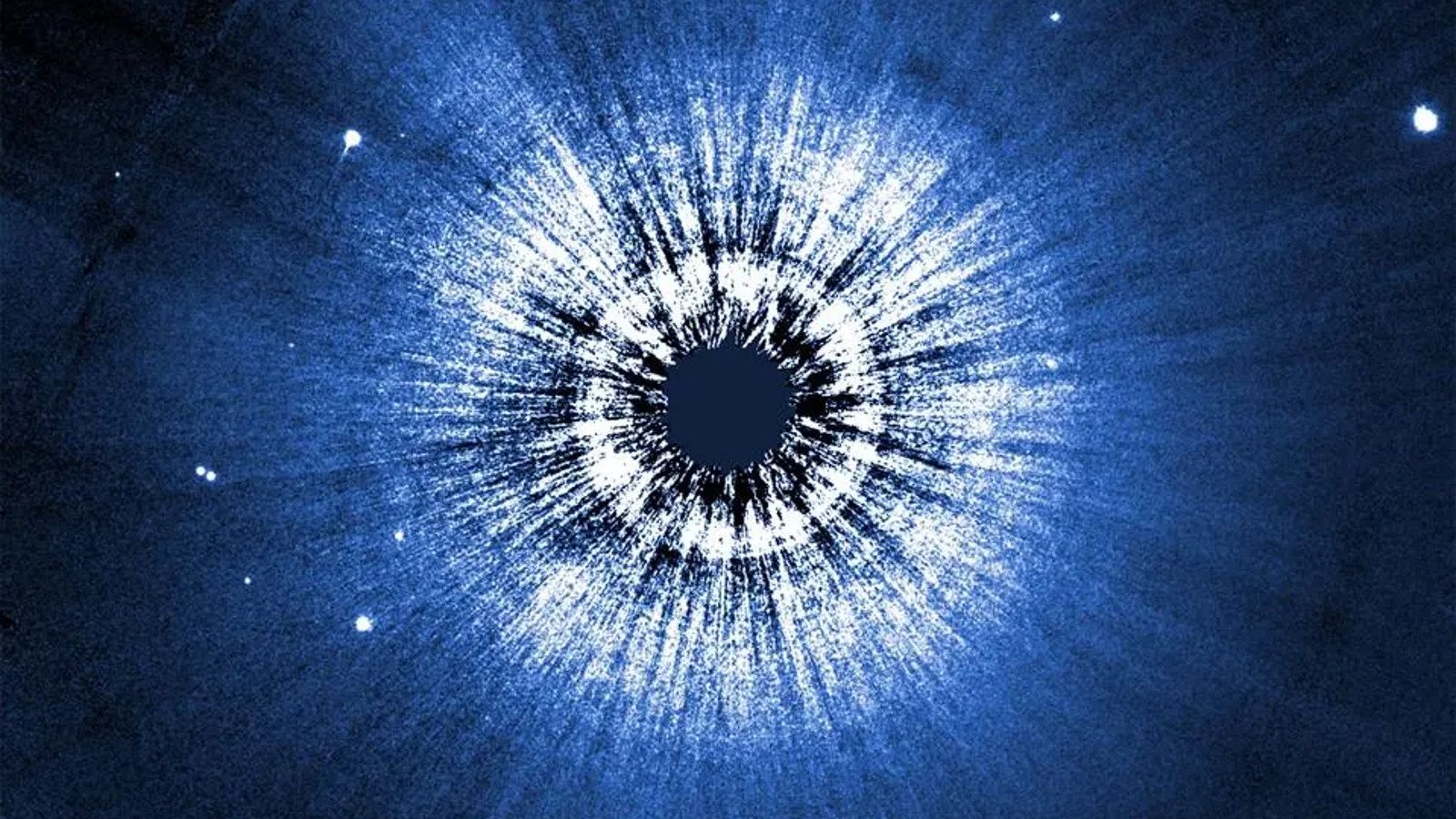

The same researchers also took images of Vega using the Hubble Space Telescope. These photos show the same uniformity to the disk as the JWST images but at a much lower resolution. The findings were shared in another paper uploaded to the preprint database arXiv.org on Nov. 1, and have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

A dark band can be spotted around Vega in both images. However, this "gap," which appears around 60 astronomical units (twice the distance of Neptune from the sun) from the star, is the result of smaller dust particles being blown farther away from Vega by stellar radiation, and not because of an exoplanet.

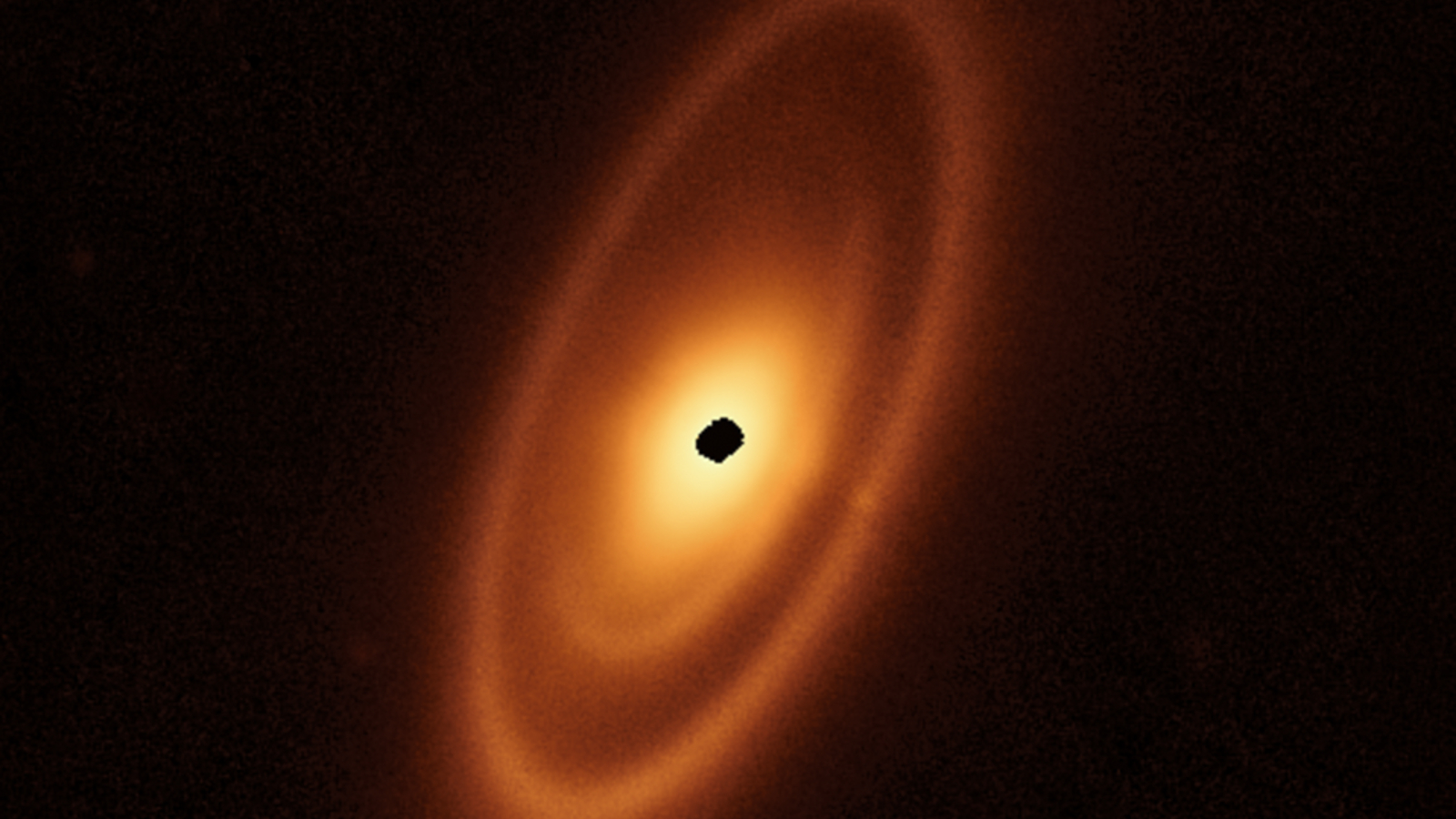

The researchers compared the new JWST image to a similar photo the telescope took of a circumstellar disk around an equally sized and similarly old star, Fomalhaut. In theory, the two stars should look the same. However, Fomalhaut has a much larger and more distinct gap in its disk, which is a sign that one or more exoplanets may have cleared the debris from this region of the system.

The researchers cannot explain why Vega cannot spawn exoplanets and Fomalhaut seemingly can. "What's puzzling is that the same physics is at work in both [systems]," study lead author Kate Su, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, said in the statement. "What's the difference? Did the circumstellar environment, or the star itself, create that difference?"

The researchers also wonder whether more non-exoplanet-forming disks could be found around other similar stars across the galaxy, which could have knock-on effects for predictions about how common alien worlds could be.

"It's making us rethink the range and variety among exoplanet systems," Su said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus