'Screaming mummy' may have died of a heart attack, researchers say

The unusual open-mouthed mummy of an ancient Egyptian woman gets a medical workup.

Updated July 23, at 2 p.m. ET.

An Egyptian woman who was mummified with her mouth open in a silent scream may have died of a heart attack, new research finds.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the mummy found widespread atherosclerosis, deposits of fatty plaques within the blood vessels. Egyptologists argue that the woman died alone of a massive heart attack and was not found for several hours, by which point rigor mortis set in. Her jaw, which may have fallen open in death, was then frozen open forever.

However, outside researchers are skeptical of this story. Mummification was a long process, and rigor mortis lasts only a few days, Andrew Wade, an anthropologist at McMaster University, told Gizmodo.

"It is far more likely that the wrappings around the jaw were simply not tight enough to hold the mouth closed, as it does tend to fall into an open position if left to its own devices," Wade said.

The mummy was discovered more than a century ago, in 1881. She had been interred at Deir el-Bahari, a tomb complex on the opposite side of the Nile from the city of Luxor. The name "Meritamun" was inscribed on her wrappings, but Egyptologists aren't sure who she was. There were several princesses in ancient Egypt named Meritamun, including the daughter of the 17th-dynasty ruler of Thebes, Seqenenre Taa II (also spelled Seqenenre Tao II), who ruled around 1558 B.C., and the daughter of the powerful Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses the Great), who became pharaoh in 1279 B.C.

Related: Photos: Female Egyptian mummy discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eternal scream

Meritamun was one of two mummies found at Deir el-Bahari wearing a frozen scream. The other has been identified as Pentawere, the son of Ramesses III, who was forced to commit suicide after allegedly participating in a plot to slash the pharaoh's throat. Pentawere was forced to kill himself after being implicated, and he was mummified poorly. He was wrapped in a sheepskin instead of linen and his organs were not removed. Nor, apparently, was his jaw secured shut, allowing his mouth to fall open.

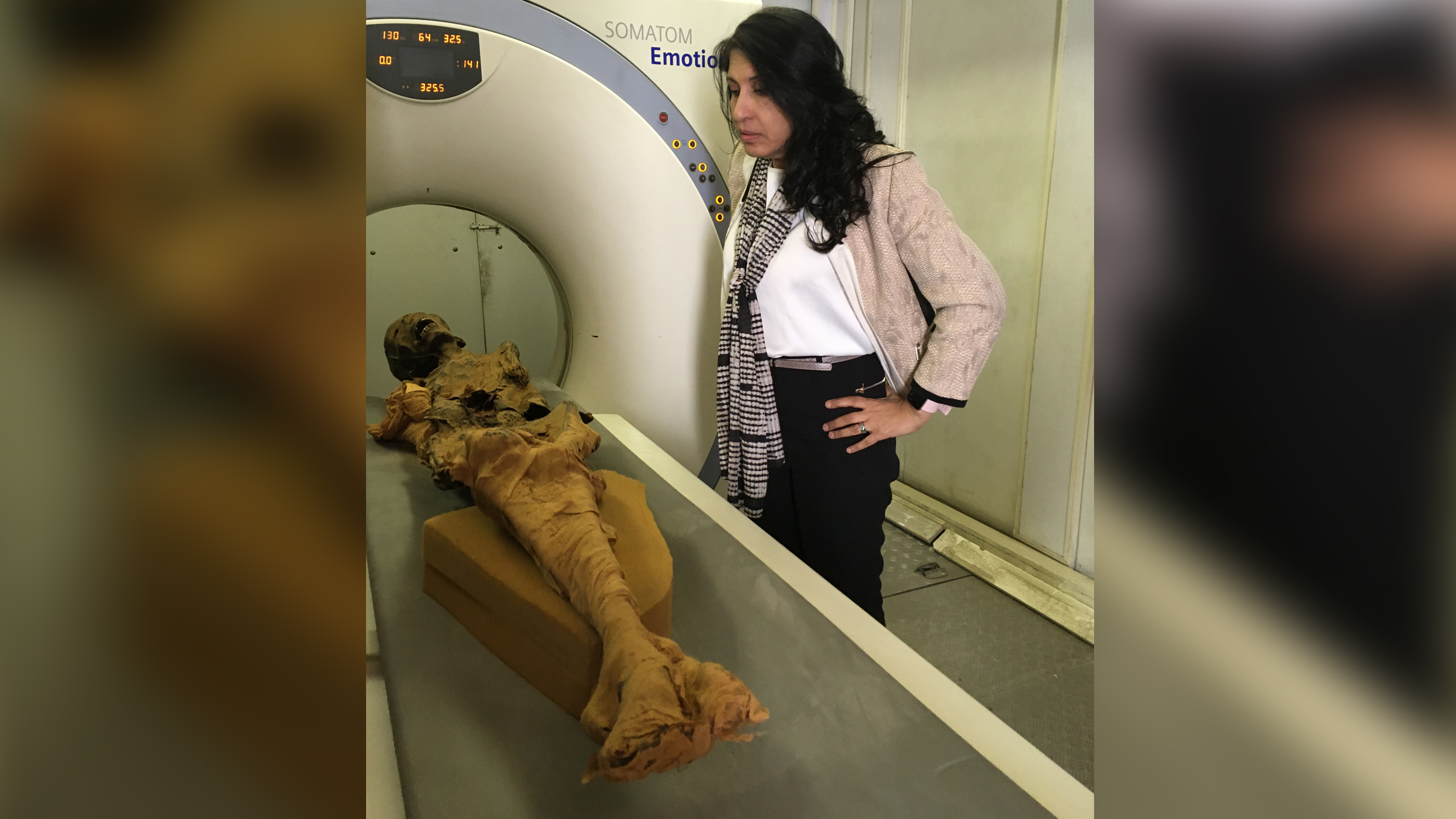

Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities, and Dr. Sahar Saleem, a radiologist at Cairo University, wanted to know if Meritamun had met a similar fate. They used CT, a method that involves rotating beams of X-rays around the body so that researchers can assemble a virtual 3D image of the subject.

Related: Photos: A look inside an ancient Egyptian mummy

The scans revealed that Meritamun was mummified well. Unlike Pentawere, she had many of her organs removed, though her heart, trachea and lungs were still present. Her abdominal cavity was packed with linen and resin. Her brain was not removed; in death, it shriveled into the back right side of her skull, echoing the rightward tilt of the mummy's head.

Meritamun stood just under 5 feet (151 centimeters) tall in life. Based on her bones and teeth, researchers believe she died in her 50s. Her teeth were riddled with cavities, and some molars were rotted down to stumps. The biggest clue to her health, though, was the atherosclerosis plaguing her blood vessels. The extensive atherosclerosis is what made the researchers speculate that Meritamun died of a heart attack. However, this diagnosis is only a guess; atherosclerosis can also kill by causing a stroke, or the blockage of a blood vessel in the brain. The researchers will publish their findings in a forthcoming issue of the Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine.

Mummy mysteries

Because Meritamun was well-mummified, Hawass and Saleem do not believe that she died in disgrace like Pentawere. But she is in an unusual position, with her gaping mouth and bent legs, crossed at the ankles.

The researchers speculate that Meritamun died alone and was not found until rigor mortis began. Rigor mortis is a stiffening of the muscles and joints that begins an hour or two after death and then fades as the body starts to decompose after two or more days. Perhaps Meritamun's embalmers began her mummification process before rigor mortis ended, the researchers wrote in their paper, and were unable to straighten her legs or secure her jaw closed. However, "screaming" mummies are not uncommon, according to a 2009 commentary in the journal Archaeology, and these grotesque expressions are the result of the jaw ligaments relaxing after death. Wrappings around the jaw typically held the mouth closed, but these could loosen.

The combination of the bent legs and open jaw makes Hawass, Saleem and their colleagues believe something else is going on with Meritamun, however.

The combination of the bent legs and open jaw makes Hawass, Saleem and their colleagues believe something else is going on with Meritamun, however.

"Mummification was so standardized and ritualized that there had to be a reason that the embalmers didn't straighten her out and place her in the usual supine position - particularly since they were apparently treating her well in preparation for the afterlife," Andrew Nelson, a professor of bioarchaeology at the University of Western Ontario, who consulted on the research, wrote in a statement. "So, some sort of combination of rigor and cadaveric spasm — although unusual — is a reasonable hypothesis." (Cadaveric spasm is muscle tightness that occurs at the moment of death.)

It is not clear when ancient Egyptians started the mummification process, Saleem told Live Science. She also said that Meritamun was well-mummified, making her skeptical that the embalmers did a poor job of securing the jaw.

“Please remember that the ancient Egyptians did not leave behind information about how they performed mummification as they intended to keep this practice as a secret,” she wrote in an email. “What we know is very little and came from ancient travelers (like Herodotus) more than 1000 years later than the peak of the practice.”

Further research on mummies like the screaming woman could help clarify the relationship of mummification with post-death phenomena like rigor mortis, she added.

The CT scan did not conclusively reveal Meritamun's family ties. One possible clue to her identity is that her brain was not removed, the researchers wrote. Brain removal was more common in 19th-dynasty mummies than 17th-dynasty mummies, they wrote. For that reason, it's plausible that Meritamun was the daughter of Seqenenre Taa II, not Ramesses the Great.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to include additional responses by Sahar Saleem and to update the affiliation of Andrew Wade.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus