Hidden 'madman' message on 'The Scream' traced back to Munch himself

Written in faint pencil lines on the corner of the world-famous painting is the phrase: "Could only have been painted by a madman!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

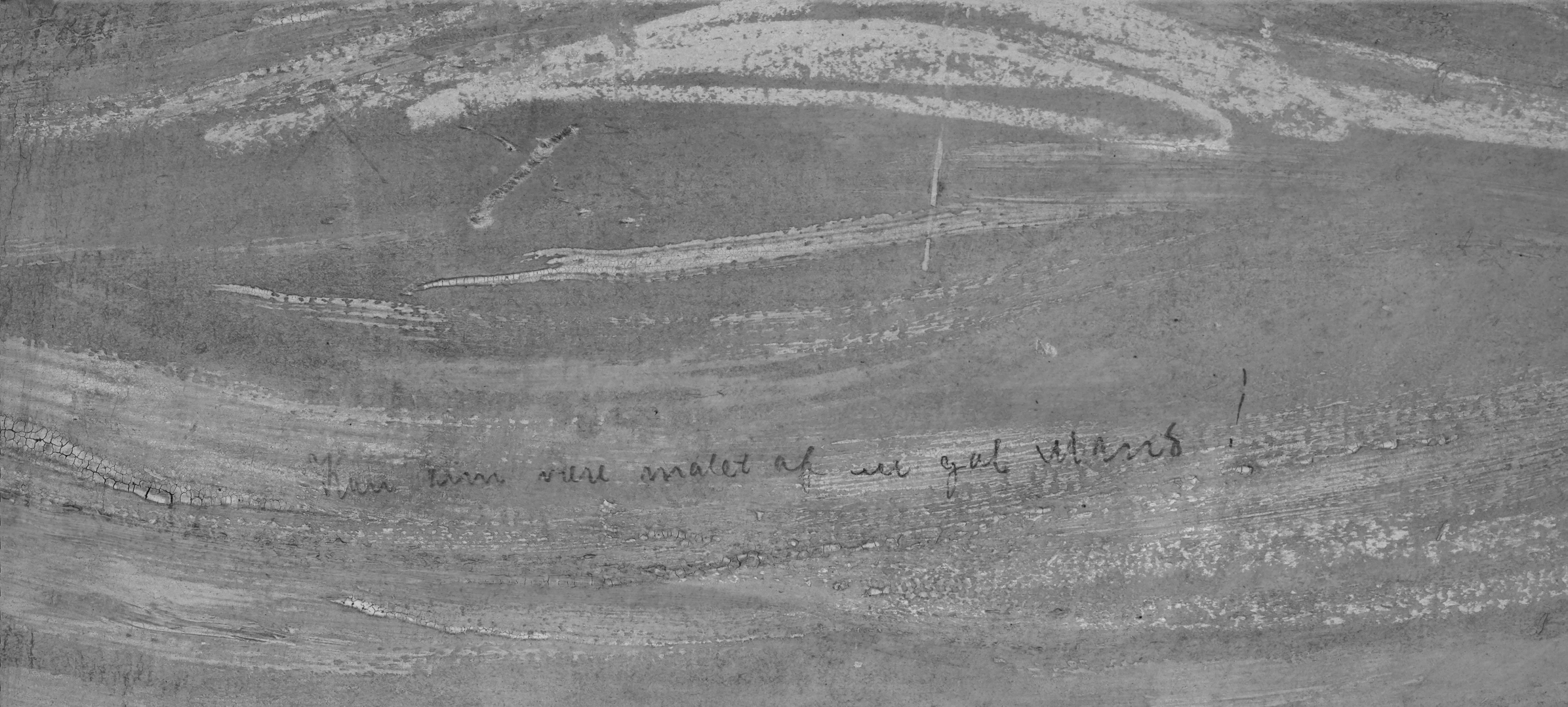

Written in tiny faint letters on the top-left corner of Edvard Munch's painting "The Scream," is a mysterious inscription that reads, "Could only have been painted by a madman!"

Experts have long debated the identity of the inscriber, with some suggesting a dissatisfied vandalizer is the author, while others pointed fingers at the Norwegian painter himself. Now, a new analysis finds that the mysterious phrase was almost undoubtedly inscribed in Munch's handwriting.

The faint inscription, written in pencil, is visible to the naked eye but it isn't very clear. "It's been very difficult to interpret," Thierry Ford, the paintings conservator at the National Museum of Norway said in a statement. "Through a microscope, you can see that the pencil lines are physically on top of the paint and have been applied after the painting was finished." But it wasn't clear when or why.

Related: 11 hidden secrets in famous works of art

This version of "The Scream" was one of four versions painted by the artist, but the only one with such an inscription, according to The New York Times.

The inscription was first mentioned by a Danish art critic in 1904 when the painting was on exhibit in Copenhagen, about 11 years after Munch painted it. The critic thought, at the time, that a member of the public wrote the message, according to the statement.

To understand the mystery, Mai Britt Guleng, the curator at the National Museum of Norway and the team took infrared photographs of the painting. The scans made the carbon from the pencil marks much clearer. The researchers compared the inscriptions with Munch's handwriting in his diaries and letters, and analyzed the details of the painting's first showing in Norway.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The writing is without a doubt Munch’s own," Guleng said in another statement. "The handwriting itself, as well as events that happened in 1895, when Munch showed the painting in Norway for the first time, all point in the same direction."

The researchers hypothesize that Munch wrote this phrase after his painting was exhibited for the first time domestically at the Blomqvist gallery in Norway in 1893 (he had previously exhibited the painting several times abroad). This exhibition in Norway drew much criticism, with one art critic Henrik Grosch writing that the painting is proof people should not "consider Munch a serious man with a normal brain," according to the statement.

At the time, the Student Society in Kristiania held a discussion event about his paintings, where some people expressed positive views about his art, but others, such as medical student Johan Scharffenberg questioned Munch's mental state. Munch was likely there and evidently took those comments to heart, as he brought up the event in his letters and diary entries several times in the decades following, according to the statements.

Munch was also very concerned, in general, about hereditary diseases, as multiple members of his family suffered from mental illness.

"The theory is that Munch wrote this after hearing Scharffenberg's judgment on his mental health, sometime in or after 1895. It is reasonable to assume that he did it quite soon after, either during or following the exhibition in Kristiania," Guleng said. "The inscription can be read as an ironic comment, but at the same time as an expression of the artist's vulnerability."

This painting will be displayed at the new National Museum of Norway once it opens in Oslo in 2022.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus