Rare 'teardrop' star and its invisible partner are doomed to explode in a massive supernova

The star system is the closest Type Ia supernova candidate ever found near Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have discovered a rare, teardrop-shaped star swirling through the cosmos some 1,500 light-years from the sun.

Why does the star cry? Because it is in a toxic relationship with a partner that is literally ripping the life from its body. In stellar relationships like these, there is no amicable uncoupling; the romance only ends when both stars explode in a violent, thermonuclear explosion that's visible across the galaxy. You'd cry, too.

But astronomers (cosmic paparazzi that they are) are fired up about this twisted stellar relationship. The star system, named HD265435, is one of only three known binary star systems in the universe — and the closest one to Earth — that is clearly destined to end in a Type Ia supernova, according to a study published July 12 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

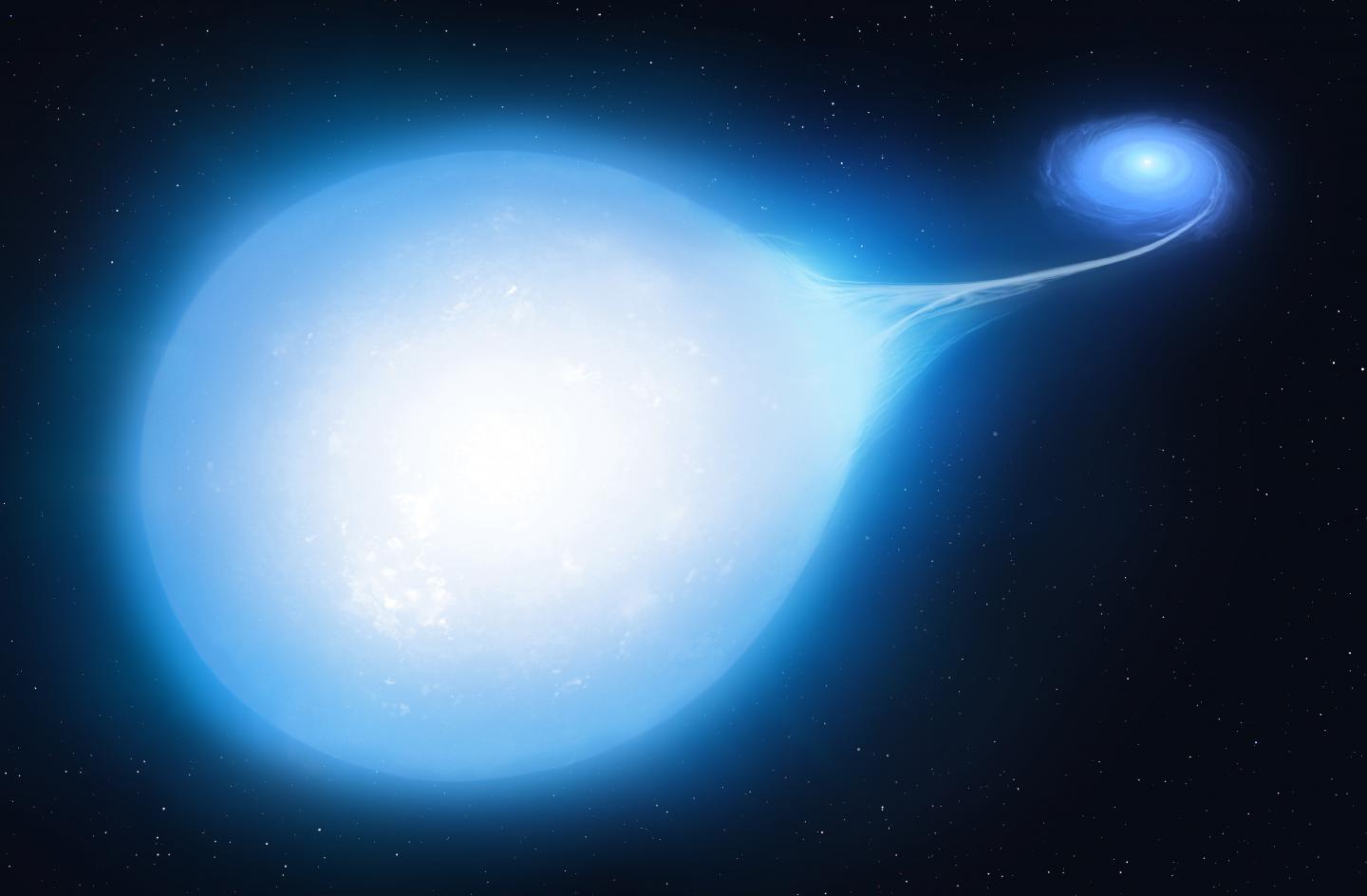

These types of stellar explosions occur when a white dwarf (the shriveled husk of an old, collapsed star) shares an orbit with a larger, younger star that still has some fuel left to burn. Small but gravitationally massive, the white dwarf gladly gobbles up this fuel, yanking so much matter away from its companion that the younger star begins to change shape from a sphere into an ellipse, or teardrop. The older star grows larger and larger over millions of years, finally becoming too big for its own good. Nuclear reactions reignite in its core, the dwarf goes boom and both stars become an irradiated smudge of gas and dust in the night sky.

Related: 12 Trippy objects hidden in the zodiac

Supernovas are easy enough to spot once the blast goes off (one infamous explosion lingered in Earth's sky for 23 days and nights in A.D. 1054), but finding the doomed star systems that lead to Type Ia explosions is much trickier. That's partly because white dwarfs are extremely dim and small, packing the mass of a sun into a ball about as wide as Earth, according to NASA.

Finding a dwarf's ill-fated companion star isn't much easier, but because these younger stars tend to be much brighter, they offer a few telltale clues, the authors of the new study wrote. One is an "ellipsoid" shape, suggesting that something massive is tugging on one side of the star and deforming it. Another clue is a rapidly pulsing light signature, which hints at a binary system where two stars are orbiting each other extremely closely and quickly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using observations from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, the researchers discovered that HD265435 fit both criteria. From these details, the team calculated the bright star's distance and mass, which allowed the researchers to make some informed estimates about the size and age of the young star’s invisible companion star.

The team found that the visible star contains about 60% the mass of the sun, suggesting that the visible star isn't too far from collapsing into a white dwarf itself. The star's invisible companion, meanwhile, fits the white dwarf profile perfectly, packing roughly one solar mass into a sphere slightly smaller than Earth.

These two stars fully orbit each other once every 90 minutes or so, indicating that they are extremely close and will probably merge completely millions of years from now. Together, the pair has the right total mass to suggest that a Type Ia supernova is on the horizon — just another 70 million years or so away, the authors concluded.

Obviously, none of us will be around to watch this stellar duo fall apart (or rather, blow apart). But finding real-world examples of binary systems doomed to go boom is no easy feat, and studying them could help astronomers better understand the still-mysterious mechanisms that power these tremendous cosmic explosions. Perhaps sadly for HD265435, that means the paparazzi lenses of Earth's space telescopes will be trained on the star system's messy relationship for ages to come.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus