Platypuses glow an eerie blue-green under UV light

Because being a duck-billed, egg-laying, venomous weirdo wasn't strange enough.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

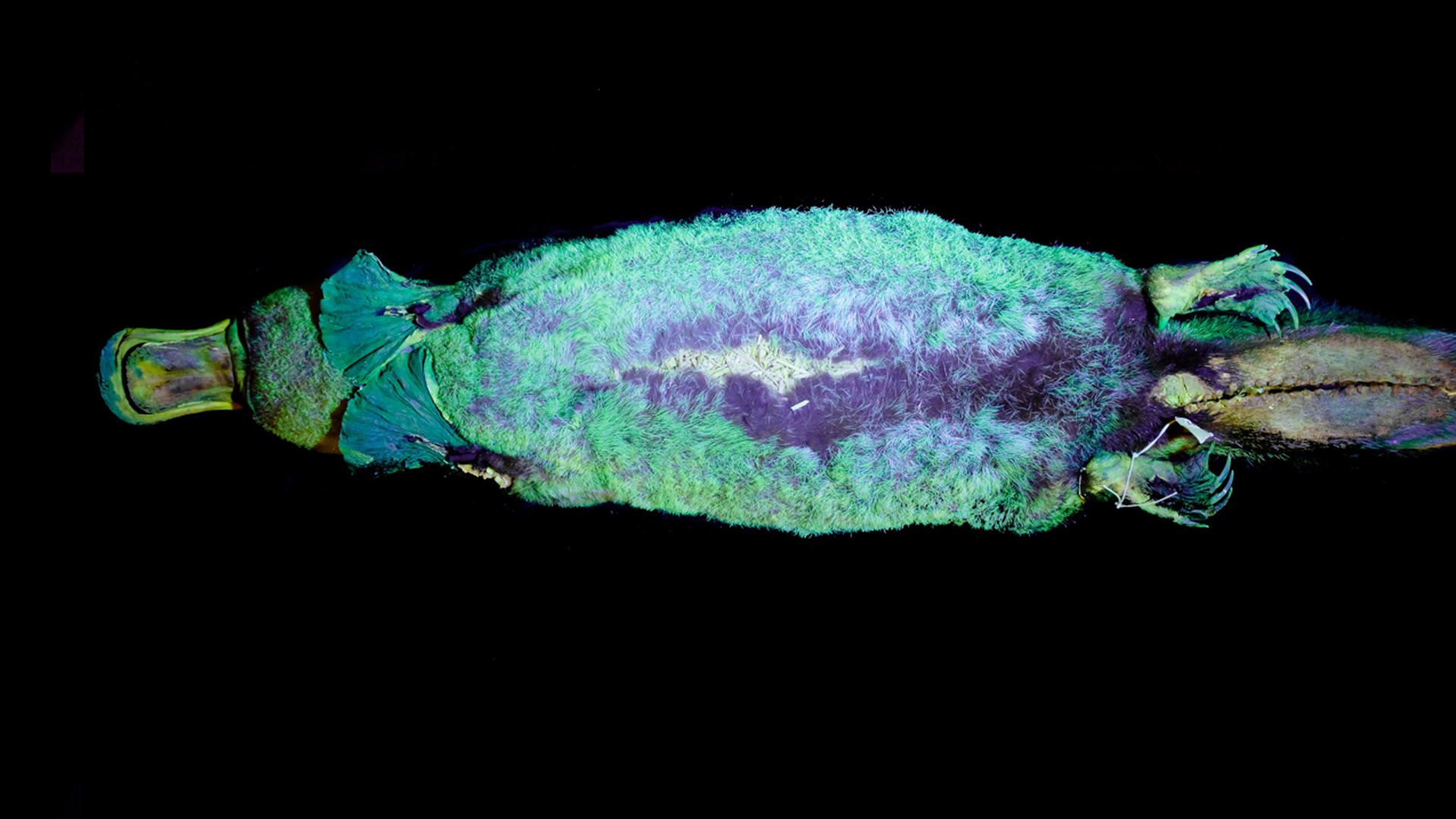

Duck-billed, egg-laying platypuses just got a little weirder: It turns out their fur glows green and blue under ultraviolet (UV) light.

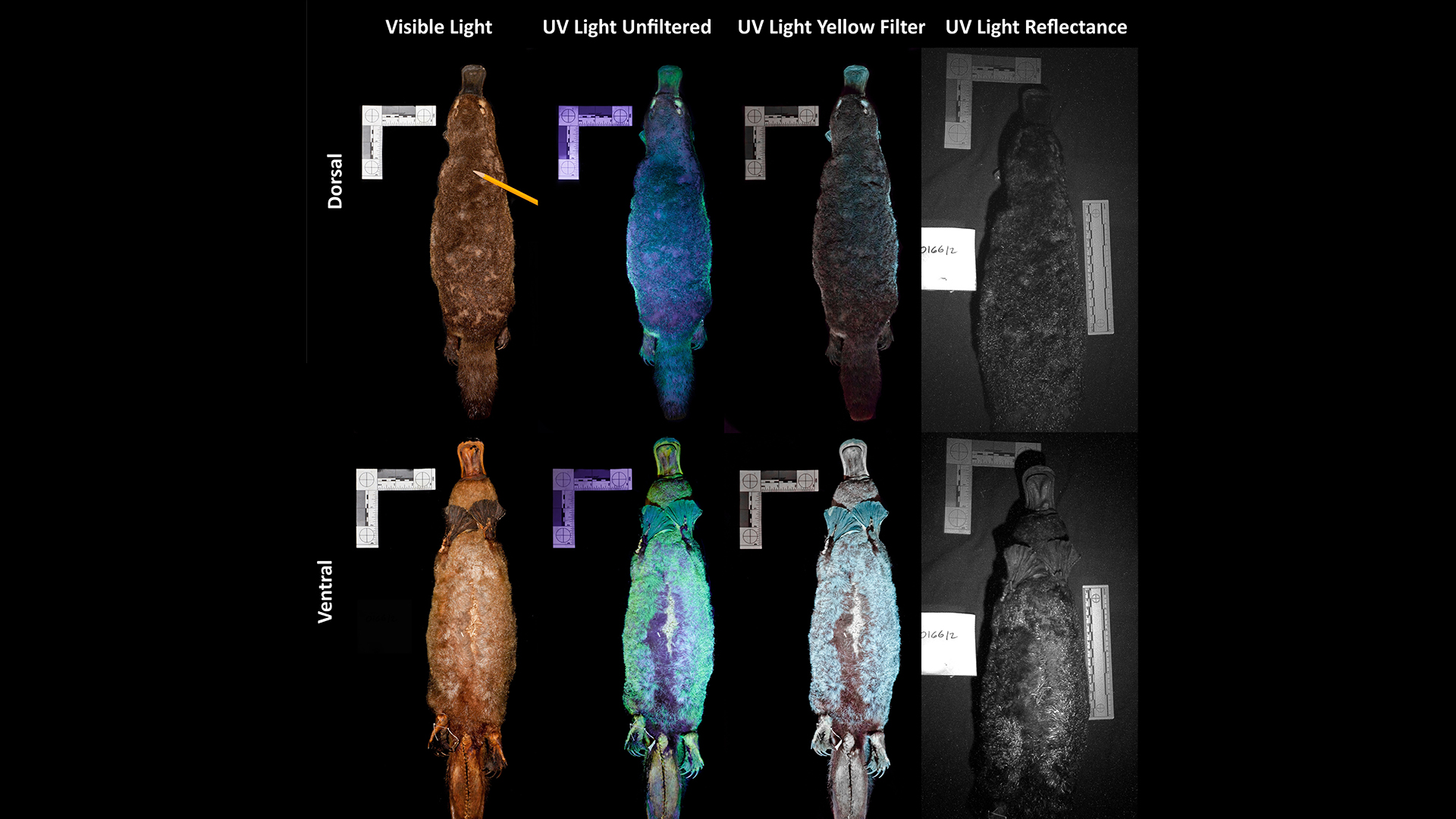

Under visible light a platypus’s extremely dense fur — which insulates and protects them in cold water — is a drab brown, so the trippy glow revealed under UV light on a stuffed museum specimen was a big surprise.

Biofluorescence — absorbing and re-emitting light as a different color — is widespread in fish, amphibians, birds and reptiles. But the trait is much rarer in mammals, and this is the first evidence of biofluorescence in egg-laying mammals, also known as monotremes, scientists reported in a new study.

Related: Extreme life on Earth: 8 bizarre creatures

Prior to this discovery, biofluorescence was known in only two mammals: flying squirrels, which are placental mammals, and opossums, which are marsupials, according to the study, published online Oct. 15 in the journal Mammalia.

Study co-author Allison Kohler, a doctoral candidate in the Texas A&M University Wildlife and Fisheries Department in College Station, Texas, had previously tested museum specimens of flying squirrels and found that all three North American species — the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus), the southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans) and the Humboldt’s flying squirrel (Glaucomys oregonensis) — glowed bright pink in UV light. Kohler, then an undergraduate at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, and her colleagues reported their results on Jan. 23, 2019, in the Journal of Mammalogy.

While testing the flying squirrel museum specimens for signs of biofluorescence, they decided to look at other mammal species in the same collections too, according to a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We were preparing for our second day at the Field Museum in Chicago to document biofluorescence in New World flying squirrels, and I started wondering how broadly distributed this trait might be within the animal kingdom," said Erik Olson, co-author of the new study and an associate professor of natural resources at Northland College. The researchers knew that platypuses — like flying squirrels — were active at night and during twilight, when an eerie glow would be visible. This made platypuses promising candidates for finding biofluorescence in monotremes, Olson told Live Science in an email.

"Plus, who doesn’t want to examine a platypus specimen?" he added. "We all agreed that we should explore this idea."

"Bird-snouted flat-foot"

Platypuses are semiaquatic and live in eastern Australia, and they are such a peculiar hodgepodge of body parts that they seem cobbled together from unrelated animals; so perhaps fittingly, their scientific name, Ornithorhynchus anatinus, means bird-snouted flat-foot, according to London's Natural History Museum (NHM).

These oddball mammals have furry bodies; flat and hairless beaver-like tails; webbed feet (males also have spurs on their hind legs that are loaded with venom); and broad bills like a duck's. When 19th-century Europeans first saw preserved skins of these strange-looking creatures, many experts thought the animal was a taxidermy hoax, with a duck's beak sewn to a mole's body, according to NHM.

The discovery of platypuses' fluorescent glow came from two specimens from Tasmania, Australia, in the collection of The Field Museum in Chicago. Both specimens — one male and one female — displayed the glow, according to the study. The scientists then tested a third specimen at the University of Nebraska State Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska; that platypus, a male, had been collected in New South Wales, Australia. It also glowed green in UV light.

The greenish-bluish color displayed a similar pattern and intensity in the male and female platypuses, suggesting it isn't a sexual trait tied to reproduction, the researchers reported.

Platypuses navigate their twilit, aquatic environments through mechanoreception, the detection of mechanical stimuli such as touch and sound, and electrostimulation, the perception of natural electrical signals. Because they don't rely heavily on sight, it's possible that their biofluorescence is not used to communicate with each other, but to reduce their visibility to predators, as in the case in some biofluorescent crustaceans.

"If there is an ecological function, it likely has to do with interactions between platypuses and other species," such as predators, Olson said in the email. "However, there is a possibility that the trait has little or no ecological function. Only further research can tell," Olson said.

Discovering the platypus's secret glow also sheds light on this trait in mammals, revealing that it's not just a few highly specialized species that glow in the dark.

"Instead, it appears across the phylogeny," the scientists reported.

These biofluorescent mammals occupy diverse ecosystems spanning three continents. And now, with the addition of the platypus, they represent all of the major mammalian lineages; placental mammals, marsupials and monotremes. One possible explanation is that mammal biofluorescence, rare though it is, may be an ancestral trait that emerged early in the group's family tree, according to the study.

"Our discovery of this trait reminds us that the natural world is still full of mysteries," Olson said. "Hopefully, our work shines a light on this unique and near threatened species."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus