Satellite snaps eerily circular holes in the clouds above Florida. What caused them?

A NASA satellite recently spotted a series of bizarre "fallstreak holes" in clouds above Florida. The circular cloud gaps have been previously (and incorrectly) linked to paranormal phenomena.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

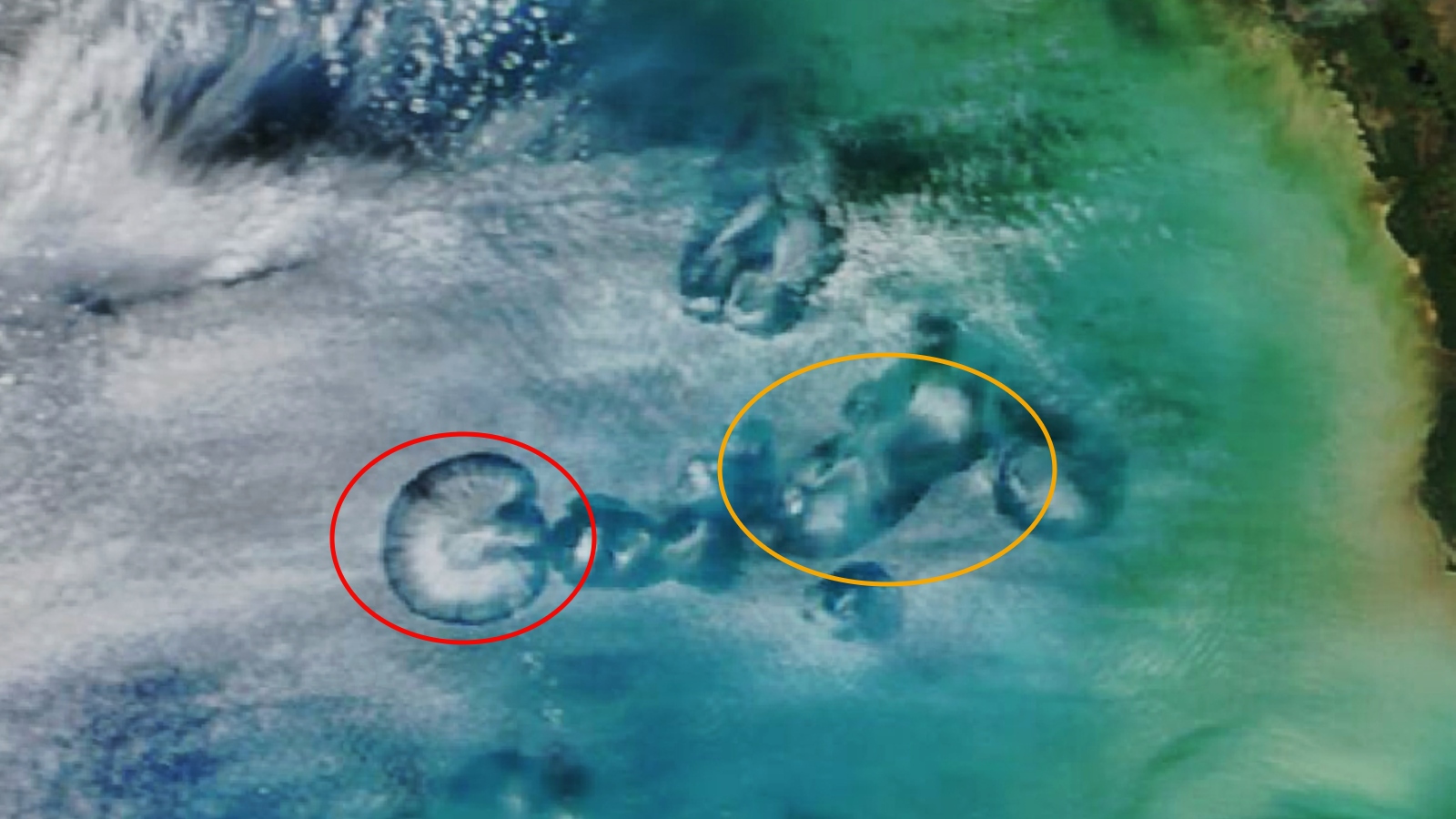

A cluster of eerily circular holes recently appeared in the clouds above Florida, a stunning new NASA image shows. The rare occurrence, which has previously (and incorrectly) been linked to UFOs, has a surprisingly simple explanation — but it took scientists more than 60 years to figure it out.

NASA's Terra satellite photographed the bizarre voids, known as fallstreak holes or hole-punch clouds, above the Gulf of Mexico off Florida's west coast on Jan. 30. NASA's Earth Observatory revealed the striking image on Feb. 26.

Unusual, circular holes like these ones first began to appear in the 1940s, sparking wild theories that they were the result of UFOs, according to the Earth Observatory. However, they are actually created by airplanes flying through the clouds.

There are two types of clouds in the new photos: cavum clouds, which are large, circular holes; and canal clouds, which have a more oblong shape. Both types most commonly occur in altocumulus clouds — supercooled bands of water vapor that float in the sky between 7,000 and 18,000 feet (2,100 and 5,500 meters) above the surface, much higher than most rain clouds.

Altocumulus clouds can be as cold as around 5 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 15 degrees Celsius) without their water droplets freezing. This is because there are fewer small particles, such as dust and pollen, at that altitude, which are needed for ice crystals to form in the air.

However, when air moves around the wings or past the propellers of airplanes, it can further cool the surrounding water vapor by as much as 36 F (20 C). At these extremely low temperatures, the droplets freeze even without particles to form around and begin to fall below the holes, creating wispy strands of cloud, known as virga.

These wispy clouds often hang below the holes they fell from and can be seen at the heart of the misty voids when viewed from above.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: What happens if you skydive through a cloud?

The holes in the new image were all created by planes taking off from Miami International Airport, according to the Earth Observatory.

Cavum and canal clouds can also form naturally when specific regions of the atmosphere cool down, but this is rare.

Scientists only discovered what was causing the more frequent artificially created holes within the last 15 years. In a 2011 study, researchers used satellite images and flight data to prove that planes were responsible.

The study also showed that the angle at which planes rise and descend through the clouds affects which type of hole will appear: A steep angle will create the more circular cavum clouds, while a more shallow angle will create stretched canal clouds.

Cavum and canal clouds normally last around one hour before they close up, but their lifespan can be impacted by other factors such as temperature, cloud density and wind speeds, the study found.

The holes pose no threat to people on the ground but they can slightly increase the amount of precipitation that occurs in the areas surrounding airports, the study showed.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus