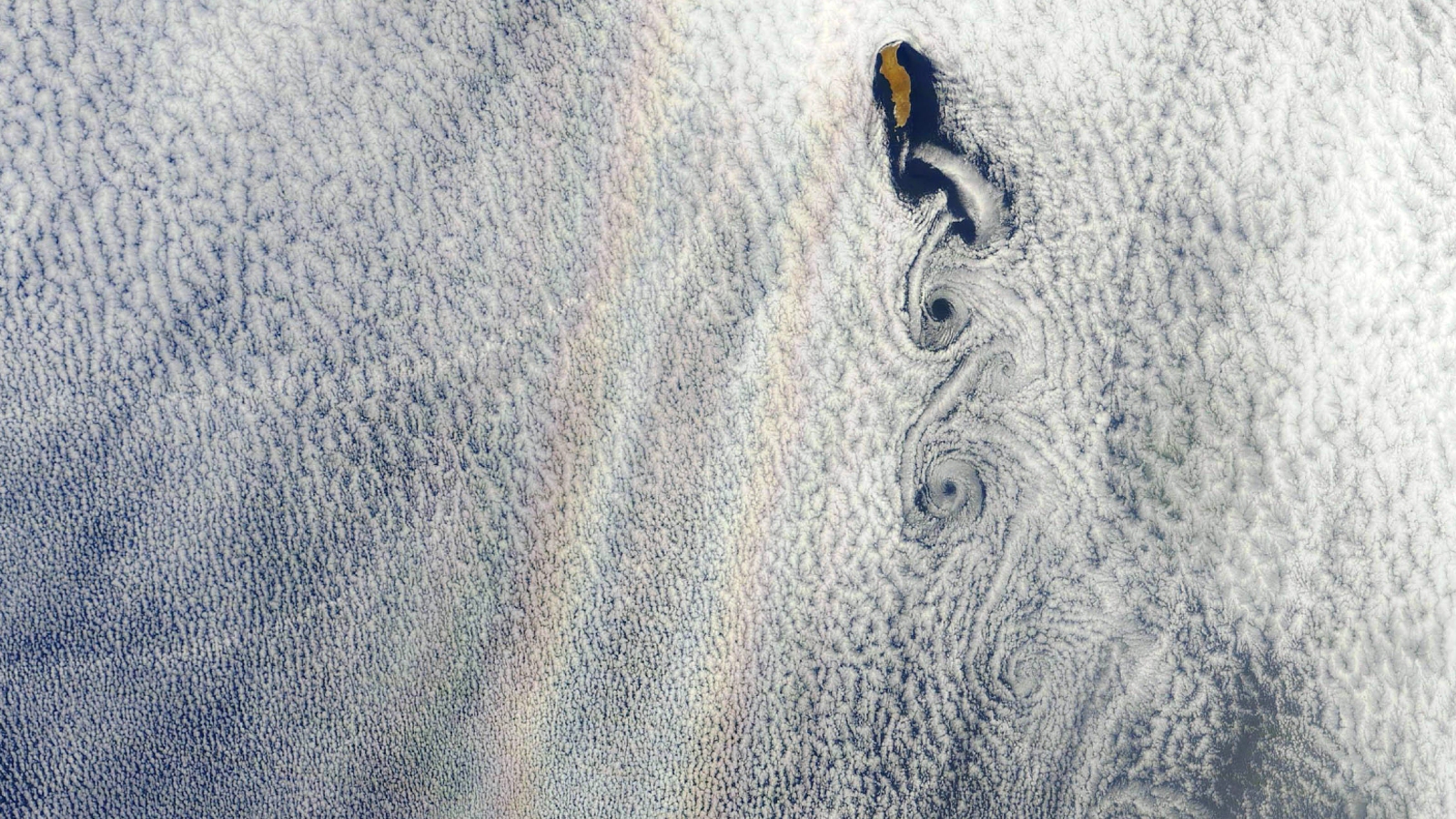

Earth from space: Warped 'double rainbow' glory appears next to rare cloud swirls over Mexican island

A 2012 satellite photo captured an unusual "double rainbow" glory appearing next to an unconnected chain of rare vortices in the clouds above Mexico's Guadalupe Island.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Guadalupe Island, Pacific Ocean

What's in the photo? A rainbow 'glory' alongside von Kármán vortices

Which satellite took the photo? NASA's Terra satellite

When was it taken? June 21, 2012

This 2012 satellite photo shows a unique perspective of a rare, rainbow-like phenomenon, known as a glory, that appeared next to a Mexican island just as the landmass spawned a separate series of equally uncommon cloud vortices.

Glories are multicolor light shows similar to rainbows, with one key difference: While rainbows form via a combination of reflection and refraction when sunlight bounces off falling rain droplets and splits into different wavelengths, glories are created by backward diffraction — when light bounces directly off even smaller water droplets in clouds or mist, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Because of this, glories only appear exactly opposite the sun, known as the anti-solar point.

This glory appeared adjacent to Guadalupe Island in the Pacific Ocean, around 150 miles (240 km) off the western coast of Mexico, and seemed to stretch for more than 300 miles (480 kilometers). Although there appear to be two distinct glories running parallel to one another, it is a single entity.

In the image, a line of eerily perfect cloud swirls, known as Von Kármán vortices, trail off the island's southernmost point. These swirling structures are formed when clouds get caught up in an airflow that has been disrupted by a tall landmass, most often above an ocean. In this case, the disruption is caused by a volcanic mountain ridge in the north of Guadalupe Island, which rises more than 4,200 feet (1,300 meters) above sea level.

While the glory and vortices are both only visible because of the thick stratocumulus clouds covering this part of the Pacific, their appearances are not connected to one another.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

Normally, glories appear as concentric multicolor circles when viewed from the ground or in the air because the diffracted light radiates outward as it bounces back toward the observer. Even from space, the rainbow-like phenomena often look circular, as was the case when NASA's Columbia space shuttle viewed the first glory from orbit in 2003.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, in this case, the Terra satellite that captured the photo "scans the Earth’s surface in swaths perpendicular to the path followed by the satellite," Earth Observatory representatives wrote. So in the image, the rainbow streaks are cross-sections of the same circular glory that has been scanned twice by the satellite.

As a result, the rainbow streaks run parallel on either side of the satellite's trajectory above our planet. The colors in each streak are perfectly inverted compared to the other: From left to right, the rainbow on the left of the image runs from red to blue and the rainbow on the right runs from blue to red.

Until recently, scientists had only ever seen glories on Earth or within the dense clouds of Venus. However, in April, astronomers detected what they believe to be the first extrasolar glory on the distant "hell planet" WASP-76 b, around 637 light-years from our planet, suggesting they might be more common than we realized.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus