Iceland volcano: 'Most powerful' eruption yet narrowly misses Grindavik but could still trigger life-threatening toxic gas plume

The submerged volcano in Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula has erupted for the fourth time in four months. The resulting lava flow narrowly missed Grindavík but could still reach the sea and potentially unleash a toxic gas plume.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A volcano in southwest Iceland has erupted without warning for the fourth time in four months, opening up massive, fiery fissures in the ground — potentially the largest it has produced to date. The eruption spewed out a river of molten rock that narrowly missed the town of Grindavík.

The eruption poses no immediate risk to local people. However, if the lava flow reaches the sea, which is still possible, it could create a giant plume of toxic gas that would be "life-threatening" to anyone near the shore, experts warn.

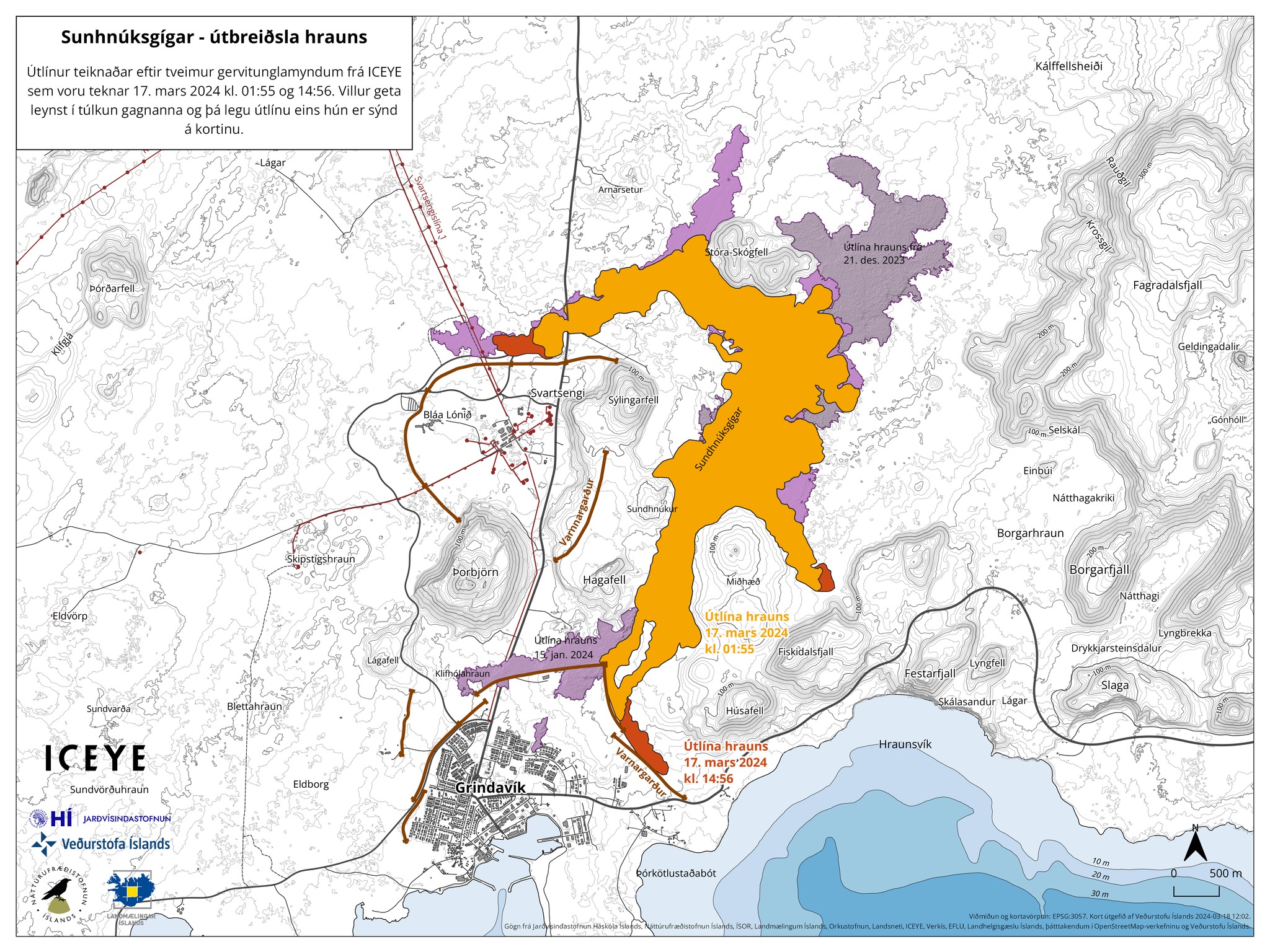

The volcano is a roughly 9 mile-long (15 kilometers) magma tunnel that runs beneath the ground, stretching north from Grindavík toward Sundhnúk in the Reykjanes Peninsula. When the hidden magma gets too close to the surface, it breaks through, triggering long and narrow fissures that violently spit out lava, ash and smoke. The most extreme activity does not last for long, but the resulting lava can travel for several miles, burning anything in its path before eventually cooling down.

The volcano first erupted in December last year after weeks of seismic activity and ground deformation, before blowing its top again in January this year. Another eruption began on Feb. 6, and lasted for just over a week.

On Saturday (March 16), the volcano suddenly erupted for a fourth time at around 8 p.m. local time with almost no warning. This time, lava broke through in three separate places, creating two fissures between Hagafell and Stóra-Skógfell, according to a translated statement from the Icelandic Met Office (IMO).

Related: Iceland eruption is part of centuries-long volcanic pulse

The largest fissure is around 1.8 miles (2.9 km) long, which is around the same size as the previous eruption, IMO reported. However, Iceland's Civil Protection estimates that the combined length of the latest fissures could be up to 2.5 miles (4 km) long, which would make the eruption the biggest since volcanic activity in the region restarted in 2021.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson, a professor of geophysics at the University of Iceland, told Icelandic news site RÚV that this eruption was the volcano's "most powerful" to date. The eruption is still ongoing at both fissures, but the rate of magma release has now reduced to between 2% and 5% of the original outpour, he added.

A lava flow from the smaller fissure came within about 1,000 feet (300 meters) of Grindavík's perimeter defenses, which were erected during the first eruption, but is now moving away from the town and toward the coast, according to the IMO.

If lava does reach the shore, rapid cooling of the molten rock could release hydrochloric acid gas, IMO representatives wrote. In high doses this colorless gas can corrode the skin, eyes and respiratory tract, leading to long-lasting injuries or even death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"In a radius of about 500m [1,640 feet] from the point where lava would come into contact with the sea, conditions would be life-threatening," IMO representatives wrote. The threat to life diminishes the further away from the shore the gas reaches, and beyond 2 miles (3 km) it is unlikely that anyone would be in danger, they added.

Grindavík lies within the toxic gas' potential danger zone. However, a majority of the town has been evacuated and the remaining residents have been warned to stay away.

It is still unclear if the lava will reach the sea. As of Sunday (March 17), the lava flow was only around 2,000 feet (600 meters) from the coast and is expected to get even closer by the end of Monday (March 18), according to the IMO. But it is slowing down.

At its peak, the molten rock was traveling at around 985 feet per hour (300 meters per hour) but has since slowed down to around 39 feet per hour (12 meters per hour), IMO reported.

There are also suggestions that the lava may have begun to pool behind a rocky outcrop, which may slow it down even further, RÚV reported.

"It is nevertheless important to be prepared for this scenario," Civil Protection representatives wrote in a statement.

Images from the latest eruption can be seen below:

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus