What will happen if the Iceland volcano finally erupts?

Experts have warned that an underground magma tunnel between a pair of Icelandic towns could erupt at any moment. But what will this eruption look like? And how far-reaching will its effects be?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

To keep up with the latest developments about the impending eruption, check out our live updates page.

Officials in Iceland are preparing for an imminent volcanic eruption from a submerged tunnel of magma, which could unleash superhot lava flows on nearby towns, a vital power plant and an iconic tourist destination.

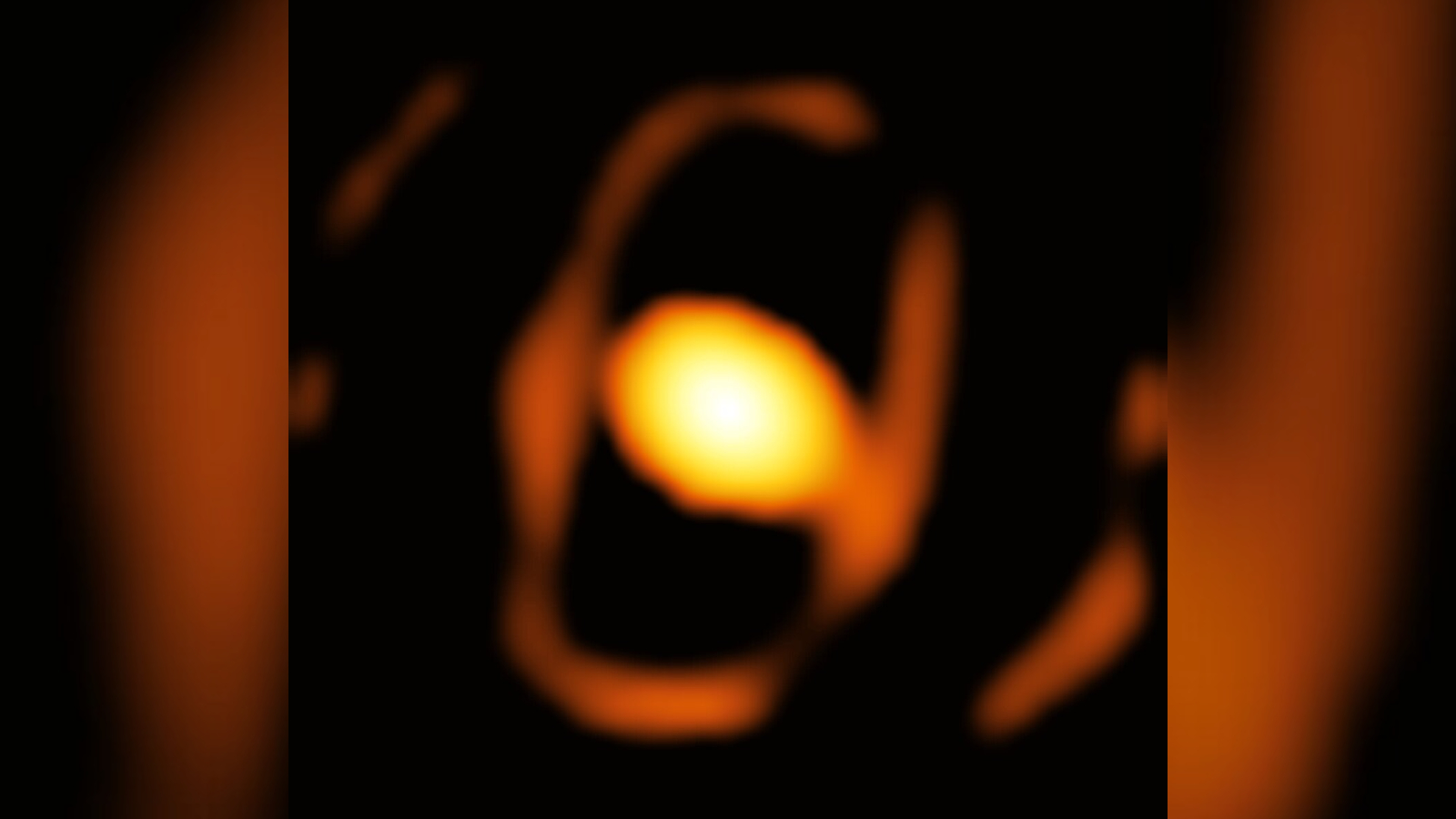

The tunnel of molten rock, known as a magma dike, stretches for around 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) between Grindavík and Sundhnúk in Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula. The underground dike has triggered thousands of earthquakes and caused significant ground deformation that has opened up sinkholes in the surface and cracks in nearby buildings and roads. As a result, local residents have been evacuated.

But this is likely just the beginning.

The Icelandic Meteorological Association (IMO) has warned that a full-blown eruption is almost certainly on its way. And other experts have suggested that the eruption could be part of a more explosive, centuries-long eruption phase for the region.

So what exactly is happening underground? What would an eruption actually look like? And how damaging could an outburst really be?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's happened so far?

On Oct. 25, seismic activity began to ramp up in the area. There were thousands of earthquakes within the space of a few hours — including two major quakes with magnitudes of 3.9 and 4.5. Seismic unrest has continued in the area since then, including a 4.8-magnitude quake on Nov. 9.

The earthquakes and ground deformation are being caused by magma entering, or intruding, into the dike at multiple points. The vast underground tunnel was first properly mapped on Nov. 11. At the time, the magma was at a minimum depth of about 2,600 feet (800 m) below the surface.

The dike sits on top of an underground crack, or fracture, in the tectonic plate beneath Iceland, Benjamin Andrews, a geologist at the Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of Natural History and director of the institute's Global Volcanism Program, told Live Science in an email. As more magma enters the dike from below, the crack will continue to grow, he added.

If the crack continues to grow and magma gets close enough to the surface, "an eruption will likely occur, " Andrews said.

What will an eruption look like?

In general, while Iceland is volcanically very active, eruptions there are quite tame: For the most part, magma slowly seeps out of the ground rather than exploding outward.

The lava is extremely hot, between 2,000 and 2,200 Fahrenheit (1,100 and 1,200 degrees Celsius) and can shoot out of the ground, Malcolm Hole, a volcanologist at the University of Aberdeen, said in a video posted on X (formerly known as Twitter). However, the molten rock has the "same sort of runniness" as golden syrup, so lava flows will move very slowly across the surface, he added.

The lava also follows Earth's topography, "the same ways as a river would," Hole said. This makes it easy to predict where it will move.

Thorvaldur Thordarson, professor of volcanology at the University of Iceland, told the Iceland Monitor that most of the lava would probably move west and into the sea. But "something always goes the other way," he added.

So how big could this eruption be? "It would likely be broadly similar to the Fagradasfjall eruption in 2021," when lava flows poured out of the main volcano in the Fagradasfjall volcanic fields, which is also located on the Reykjanes Peninsula, about 6.2 miles (10 km) away, Andrews said. This eruption near constantly spat up magma for more than six months, according to the IMO.

Similar eruptions have also recently occurred from a baby volcano near Fagradasfjall, which was born in June this year.

When will it erupt?

The latest IMO statement continues to warn that there is a "significant likelihood of a volcanic eruption in the coming days."

But there is no accurate way of telling if the eruption will occur in hours, days or weeks, Andrews said.

There is also still a chance that "the intrusion [of magma into the dike] could end with no eruption," Andrews said. Although the IMO seems pretty convinced that it will, he added.

"I predict — if an eruption occurs — that it will occur between a few days to threeish weeks," Edward W. Marshall, a researcher at the University of Iceland's Nordic Volcanological Center, told Live Science in a recent article. "If it hasn't erupted in three weeks, I don't think it will happen." After then, "cooling will begin to close the fractures," he added.

Will an eruption halt air traffic?

In 2010, the eruption of Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano created an enormous eruption plume that grounded most air traffic above Europe for more than a week, causing travel disruption for around 7 million people, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Unlike most other eruptions in Iceland, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption was very violent. This was because the volcano was covered with a thick sheet of ice, which exploded outward with great force when the magma rose up and made contact with it, Hole said. This unusual explosion meant that more ash, smoke and water vapor were ejected than normal, he added.

But the current volcanic dike is not covered in ice, meaning, "an eruption at the current site of unrest is unlikely to produce an ash cloud similar to that which disrupted air travel in 2010," Andrews said. Although there will be an eruption plume, he added.

Will toxic gases be released?

On Nov. 14, IMO sensors near Grindavík detected sulfur dioxide, a toxic volcanic gas, seeping out of the ground, IMO representatives wrote on X. This has led to speculation that an eruption could release high levels of the toxic gas, which could impact anyone who remains in the area.

"The majority of gas released in an eruption will most likely be water that was originally dissolved in the magma at depth," Andrews said. However, other gases, including sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide, will also be released, he added.

During past eruptions in Iceland, such as the eruption of Bárðarbunga in 2014 and 2015, volcanic gases caused problems with air quality in the country, Andrews said. "But I am not aware of any forecasts about potential hazardous gas emissions" from a impending eruption at Grindavík, he added.

Which locations are at risk?

Of the two towns that straddle the magma dike, Grindavík is the closest and most at risk, according to the IMO. Most of the town's roughly 2,800 residents have already been evacuated and are unlikely to permanently return unless the threat of an eruption recedes.

The Blue Lagoon resort, a famous geothermal spa that attracts more than 700,000 annual visitors, is around 3 miles (5 km) from the dike. The site has been closed to tourists until at least the end of the month, so people will not be in danger. But the lagoon could still be damaged by lava flows.

The geothermal Svartsengi power plant — which provides energy across the country and supplies hot water to local towns and villages — is located around 4 miles (6 km) from the dike. But work has already begun to dig trenches around the site to divert lava away from the site if it heads that way.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus