Archaeologists finally peer inside Egyptian mummies first found in 1615

The female mummies wore many necklaces, CT scans showed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two ancient mummies discovered in a rock-cut tomb in Egypt more than 400 years ago are finally spilling their secrets, now that scientists have CT scanned their remains, a new study finds.

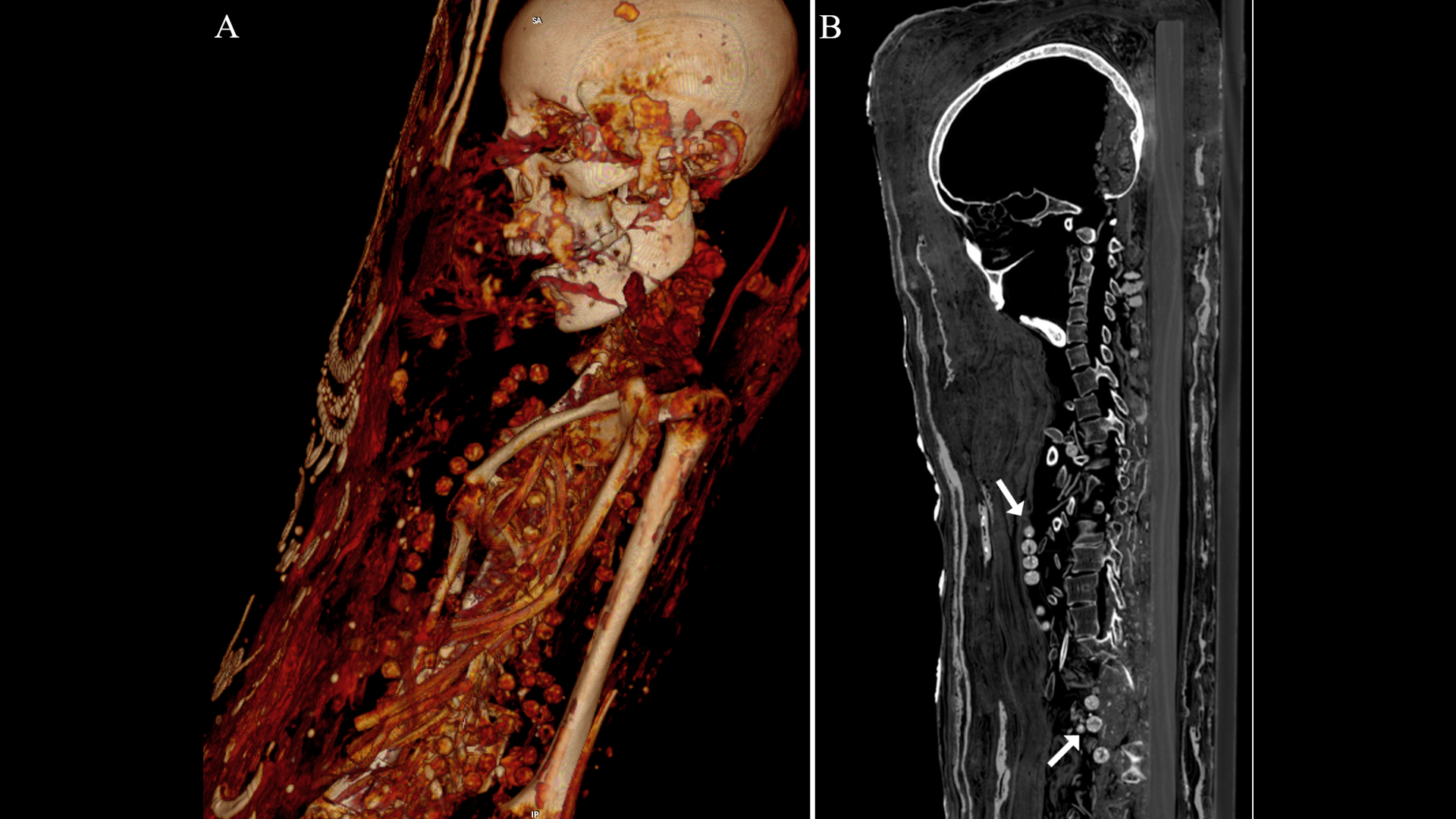

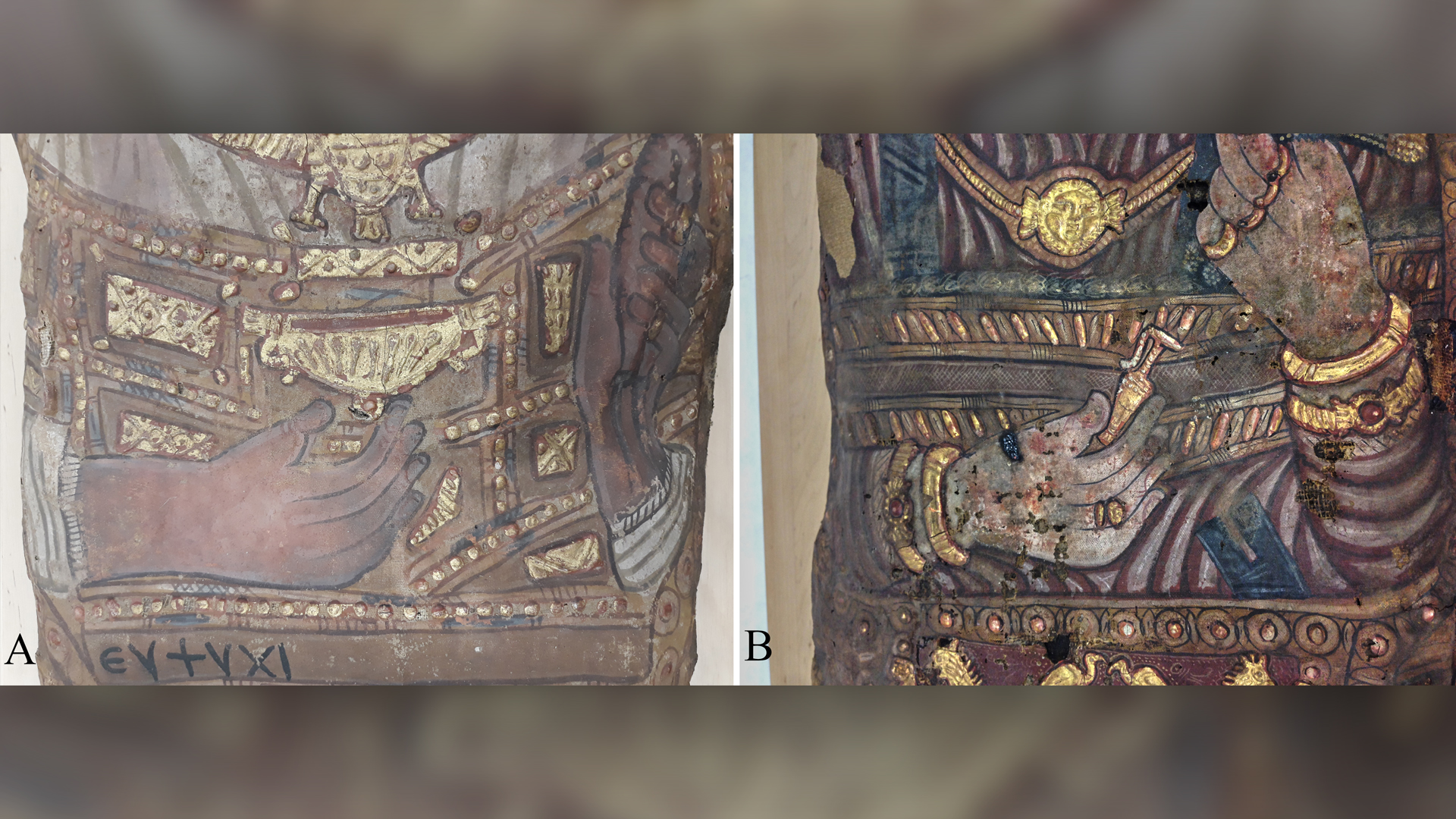

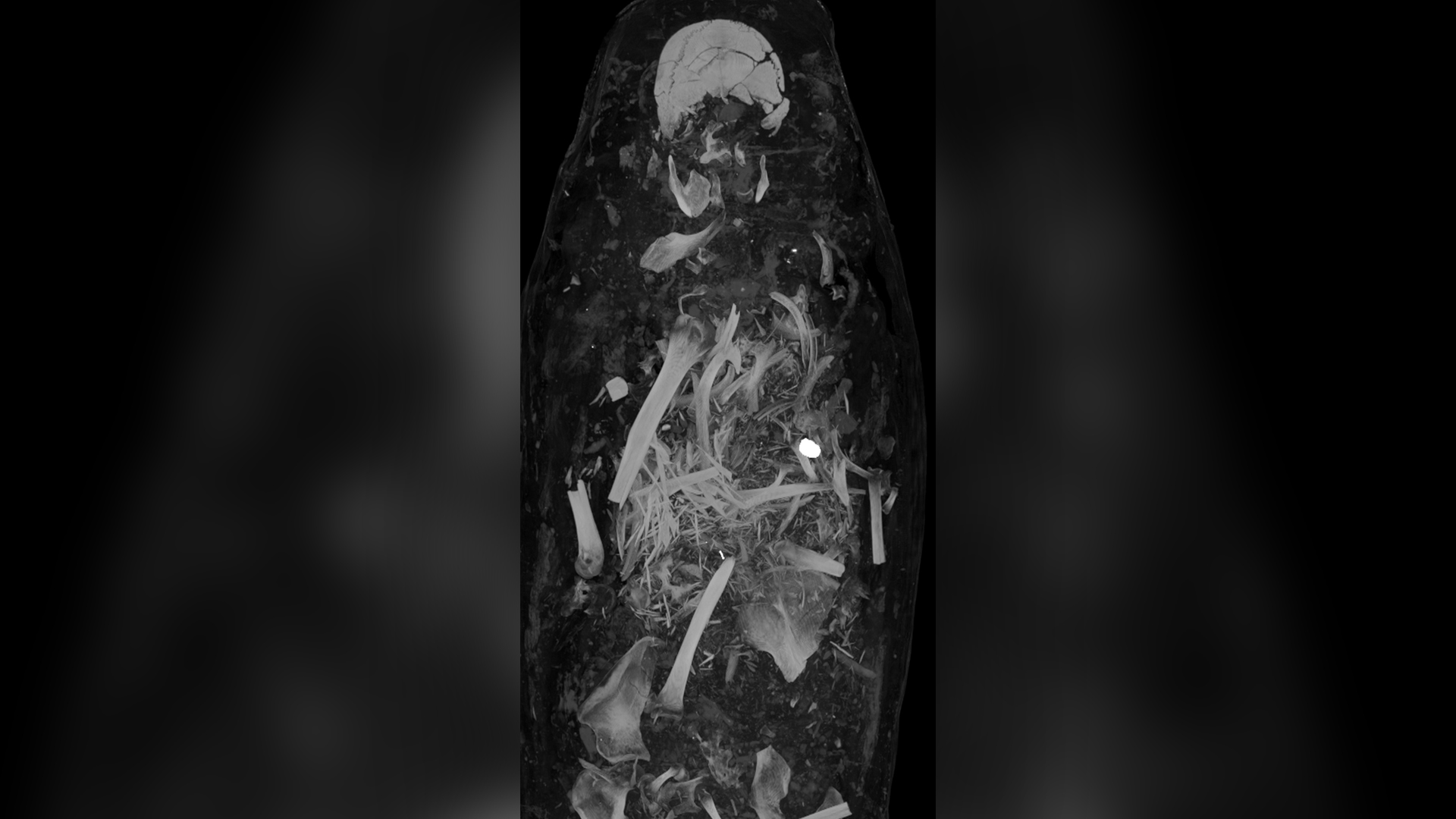

Both mummies, as well as a third on display in Egypt, represent the only known surviving "stucco-shrouded portrait mummies," from Saqqara, an ancient Egyptian necropolis. Unlike other mummies, who were buried in coffins, these individuals were placed on wooden boards, wrapped in a textile and a "beautiful mummy shroud," and decorated with 3D plaster, gold and a whole-body portrait, said study lead researcher Stephanie Zesch, a physical anthropologist and Egyptologist at the German Mummy Project at Reiss Engelhorn Museum in Mannheim, Germany.

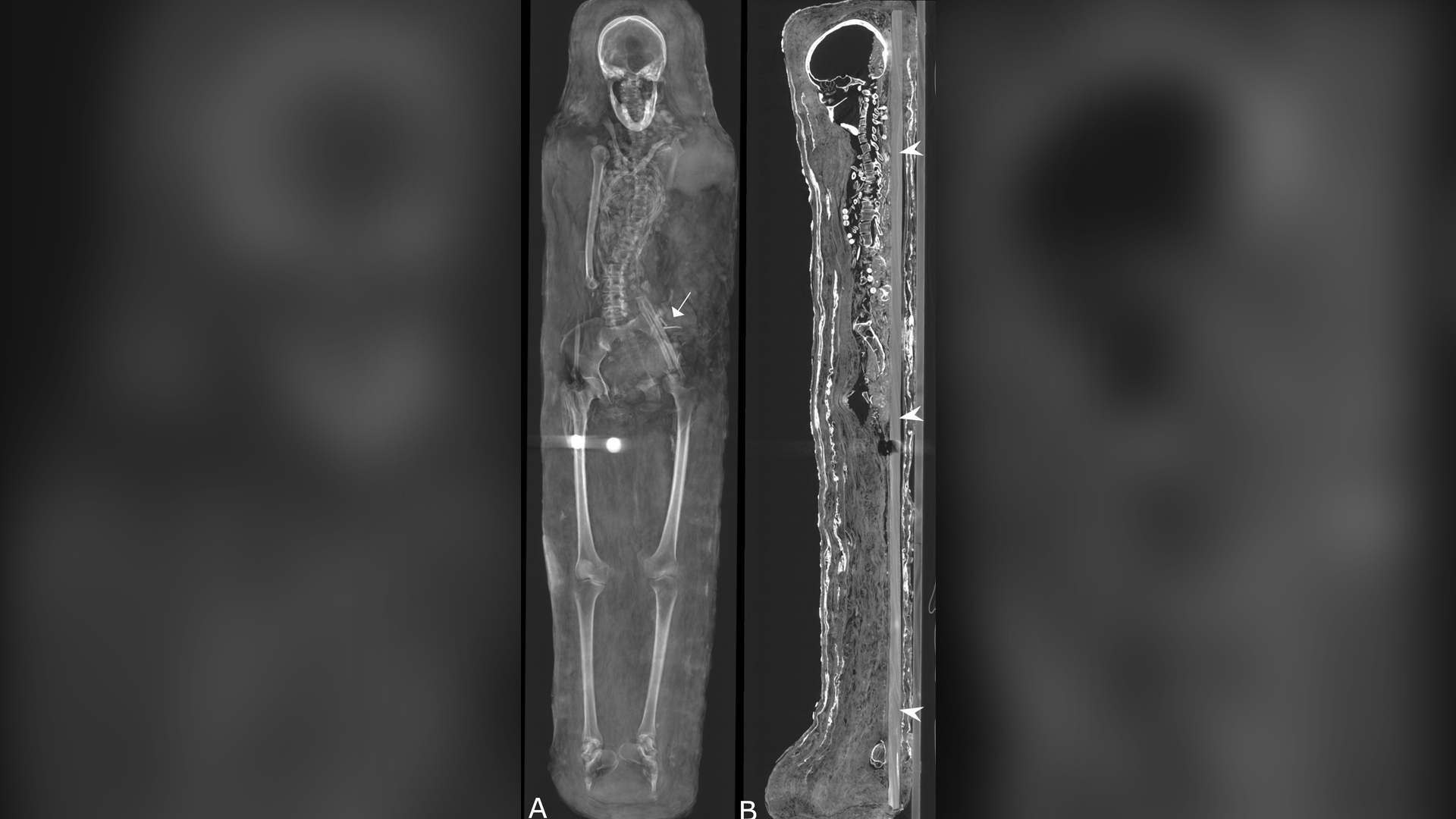

Now, CT (computed tomography) scans reveal that at least one of these three stucco-shrouded portrait mummies was buried with organs (even the brain) and that the two females were interred with beautiful necklaces, the researchers found.

Related: In photos: A look inside an Egyptian mummy

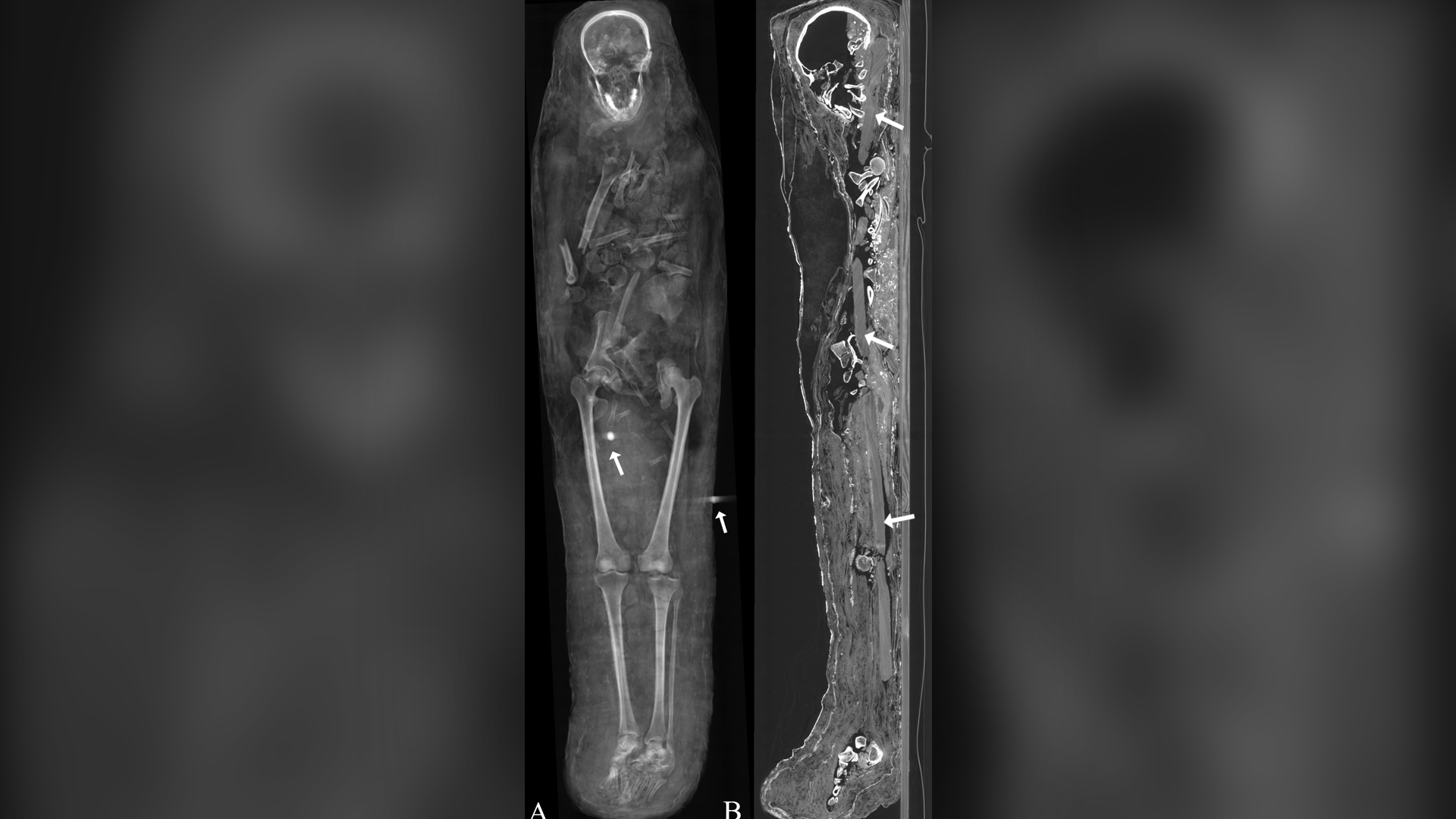

The CT scans also showed that after the deaths of these individuals — a man, woman and teenage girl dating to the late Roman period (30 B.C. to A.D. 395) — their mummies were interred with artifacts likely thought useful in the afterlife, including coins that were possibly meant to pay Charon, the Roman and Greek deity thought to carry souls across the River Styx.

The CT scans also revealed several medical problems, including arthritis in the woman. "The examination of the individuals yielded that they died at rather young ages … however, the cause of death of the individuals could not be determined," Zesch told Live Science.

Long journey

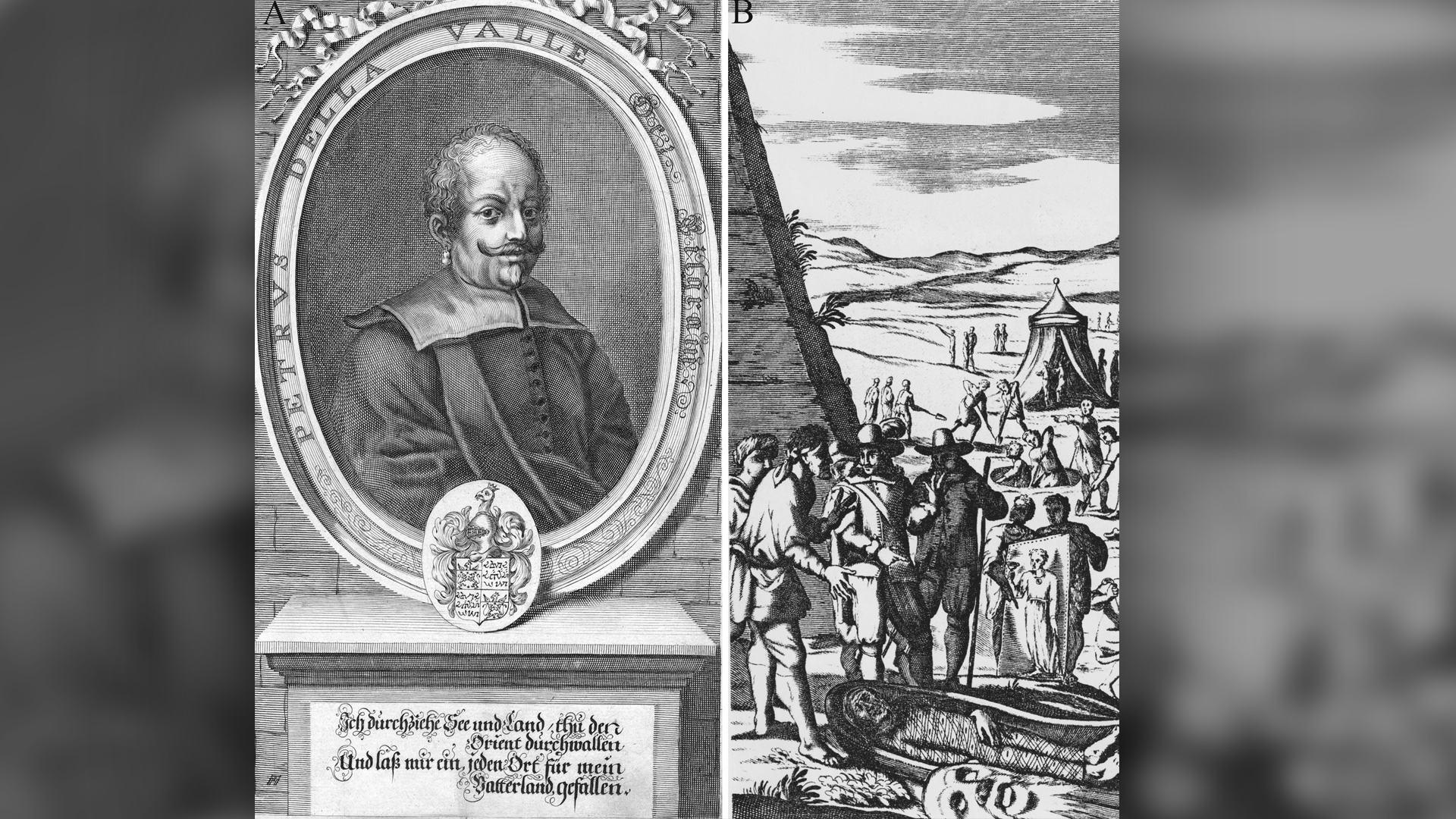

Two of these mummies have traveled far and wide. In 1615, Pietro Della Valle (1586−1652), an Italian composer, took a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and ended up traveling through Egypt. He learned about two stucco-shrouded portrait mummies — a man and woman — discovered by locals in Saqqara. Della Valle acquired these mummies and brought them to Rome, making them the "earliest examples of portrait mummies to have become known in Europe," the researchers wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After passing through several owners, and a little worse for wear, the mummies ended up in the Dresden State Art Collections in Germany, where they were X-rayed in the late 1980s. However, the CT scan revealed much more about their insides.

For instance, the CT scan revealed that the male died between the ages of 25 and 30. He stood about 5'4" inches (164 centimeters) tall, and had two unerupted permanent teeth and several cavities. Some of his bones were broken and jumbled, probably because someone unwrapped him shortly after the mummy's discovery, the researchers wrote in the study.

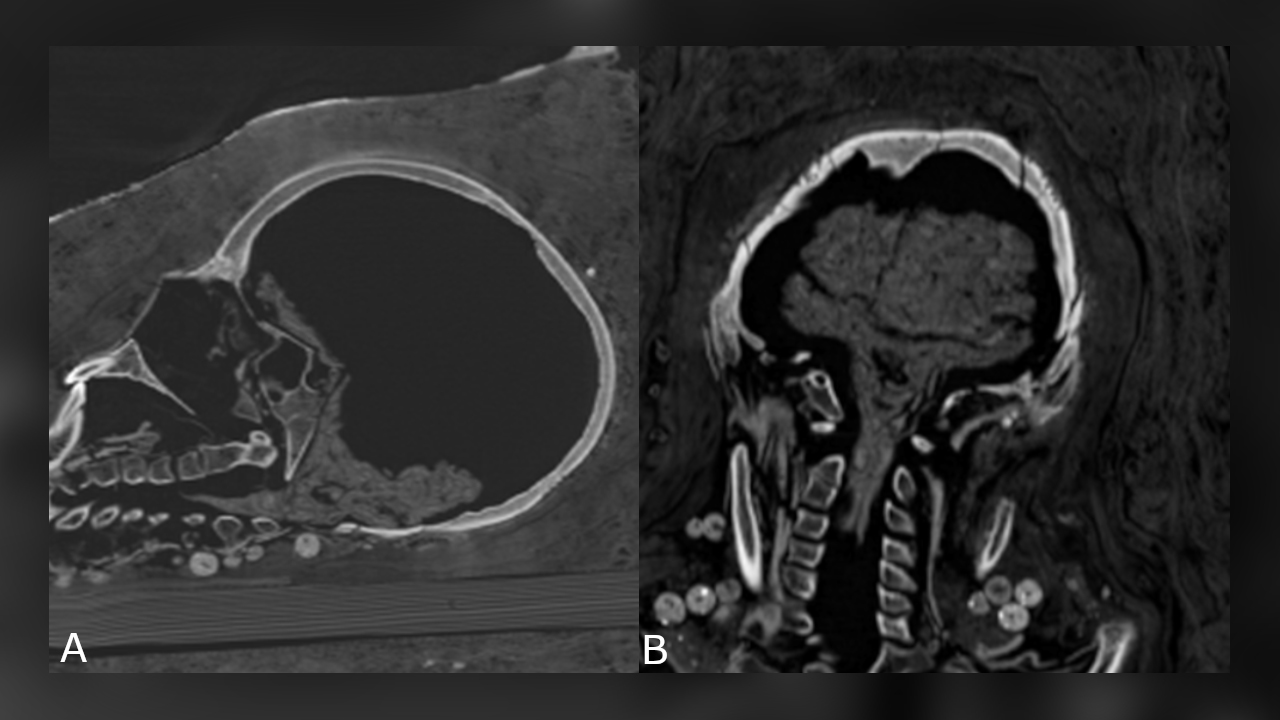

While the man's brain was not preserved, there's no evidence it was removed through his nose. Nor were many embalming substances used. Instead, he was wrapped up and painted. Two metal objects found during the CT scan are likely seals from the mummification workshop that handled his remains, Zesch said. The woman's brain wasn't preserved either, but the teenager's was — it had shrunk, but the cerebrum and brainstem were still identifiable — and the teenager's other internal organs were also present.

"We are quite sure there was no removing the brain or the internal organs" from these mummies, Zesch said. "It's very probable that those mummies were only preserved because of a kind of dehydration with the use of [the desiccation mixture] natron, but there is not a huge amount of embalming liquids."

Related: Photos: Canine catacomb was tribute to ancient death god

The woman, who died between the ages of 30 and 40, stood about 4'11" (151 cm) tall. She had advanced arthritis in her left knee. The teenager, who wore a hairpin, according to the CT scan, died between the ages of 17 and 19, and stood about 5'1" (156 cm) tall. She had a benign tumor in her spine known as a vertebral hemangioma, which is more common in people over 40, the researchers said.

Both women were buried with multiple necklaces. It's exciting to see these necklaces, but it's not unexpected, Zesch said. "Because of these very precious shrouds, we are sure that those individuals have to be members of the higher socioeconomic class," meaning that they could have easily afforded jewelry, Zesch said.

Zesch noted that she studied the three mummies with a multidisciplinary team from the German Mummy Project, the Dresden State Art Collections, the Institute for Mummy Studies at Eurac Research in Bolzano, Italy and the American-Egyptian Horus Study Group. Their work informed a now-live interactive exhibit of the male and female mummy in Dresden. The teenager's mummy is on display at the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt.

The study was published online Nov. 4 in the journal PLOS One.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus