10 stunning fossils from 2022 that didn't come from dinosaurs

Not all the best fossils belong to dinosaurs. Here are some of our favorite non-dino fossil stories dug up in 2022.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When it comes to fossils, dinosaurs usually dominate the headlines. But many amazing and scientifically important non-dino fossil discoveries get dug up every year that deserve just as much respect. And 2022 was no different. From the oldest fossilized brain and ancient panda teeth to mangled "dragon" bones and a 3D fish face, here are some of our favorites.

Oldest fossilized brain

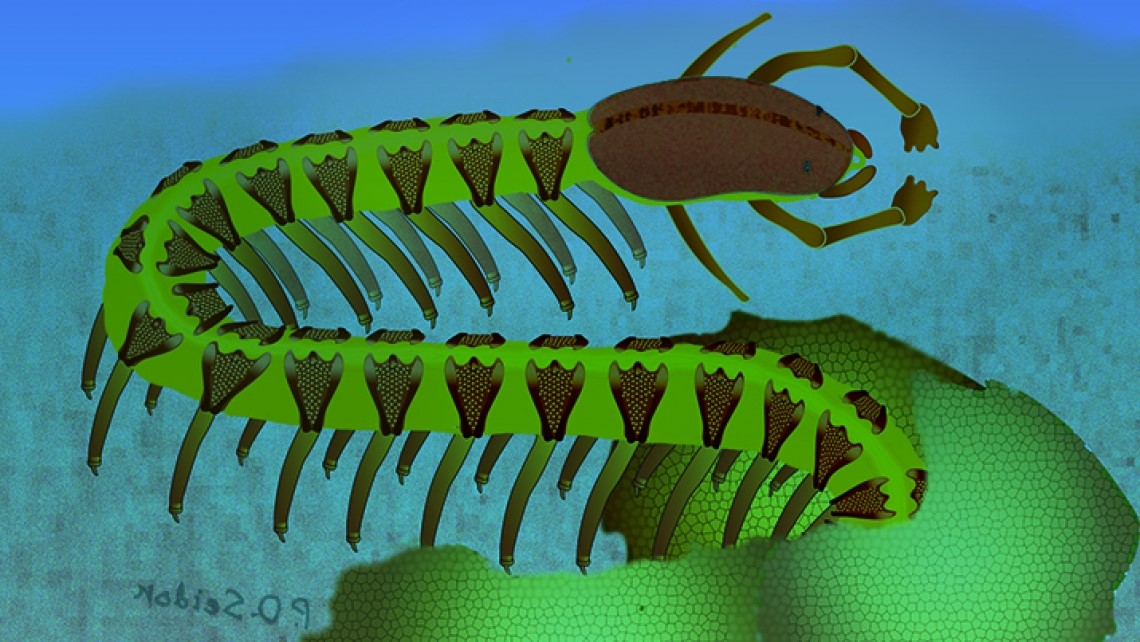

A 525 million-year-old fossilized worm unearthed in China has what is likely the oldest example of a brain ever discovered.

The ancient worm-like critter, known as Cardiodictyon catenulum, belongs to the phylum Lobopodia — a group of extinct, seafloor-dwelling arthropod ancestors with armored shells and stubby legs that were abundant during the Cambrian period (541 million to 485.4 million years ago).

The specimen was first discovered in 1984, but the original researchers "would not even dare to look at it in hopes of finding a brain." When the new team reanalyzed the fossil, they found not just a brain but also an entire delicately preserved nervous system.

The shape of the brain and nervous system could also solve a longstanding debate about the evolution of brains in arthropods.

Read more: Fossilized brain of 525 million-year-old deep sea worm likely the oldest ever discovered

Titanic 12-foot turtle

Paleontologists have unearthed an extinct, never-before-seen species of giant sea turtle in Spain. The massive reptile likely had a body length of around 12.3 feet (3.7 meters) — more than double the size of modern marine turtles — and is the largest turtle species ever uncovered in Europe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new species, which researchers named Leviathanochelys aenigmatica, was identified from a complete pelvis fossil and fragments of fossilized shell. It likely cruised Europe's ancient oceans between 83.6 million and 72.1 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago).

The world's largest-ever turtle is the extinct Archelon ischyros, which lived in North America and had a maximum body length of 15 feet (4.6 m). The new finding suggests that gigantism in turtles likely evolved in at least two separate evolutionary lineages.

Read more: Titanic 12-foot turtle cruised the ocean 80 million years ago, newfound fossils show

Frog sea "death trap"

Between the 1930s and 1950s more than 150 fossilized frogs were unearthed at a fossil site in Germany. Bizarrely, all the frogs seemed to have been completely healthy when they died, which left scientists puzzling to figure out what killed them.

In a new study, researchers suggested that the frogs may have died while having aggressive underwater sex. In some species of modern frogs that mate in water, males often hold females under the surface as they mount them, which can sometimes cause the females to drown. Geological records show that the fossil site was a marshy swampland around 45 million years ago when the frogs are believed to have died, which suggests these animals could have mated in the same way.

Past explanations for the fossilized frogs’ demise include extreme environmental changes, such as flooding, drought or oxygen depletion. But through a process of elimination, the study researchers believe their theory is the "only explanation that makes sense."

Read more: 'Ancient death trap' preserved hundreds of fossilized frogs that drowned during sex

Europe's last panda

A never-before-seen species of panda that was likely the last of its kind to roam Europe was identified after researchers rediscovered a pair of fossilized teeth that had been lost in the archives of a museum in Bulgaria.

The new species, named Agriarctos nikolovi, had much larger teeth than seen in other European pandas, and so it was most likely similar in size to living giant pandas in Asia. However, its tooth structure hints that these teeth were weaker than giant panda teeth, suggesting that A. nikolovi likely had a more varied diet and probably chewed on soft vegetation rather than chomping on hard bamboo.

Until now, the youngest European panda dated back to around 10 million years ago. But the new fossils are around 6 million years old, which suggests that pandas roamed the continent more recently than previously believed.

Researchers believe A. nikolovi was eventually wiped out by extreme ancient climate change.

Read more: Europe’s last pandas were giant weaklings who couldn’t even eat bamboo

Bizarre shark-like fish

Researchers in China uncovered the remains of a 439 million-year-old shark-like fish with unusual features that "set it apart from any known vertebrate."

The newfound species, Fanjingshania renovata, was covered in spines and "bony armor" and is the oldest undisputed jawed vertebrate ever discovered. The team painstakingly recreated what the ancient fish might have looked like using thousands of fossilized skeletal fragments, scales and teeth.

The species belongs to a group of shark-like creatures known as acanthodians, which share similarities with chondrichthyans — a class that includes modern sharks and rays — and osteichthyans, the superclass of bony fish. Researchers suspect that F. renovata was closely related to an undiscovered common ancestor between both groups.

Read more: Bizarre, primeval sharklike fish is unlike any vertebrate ever discovered

Reconstructed salamander skull

A bizarre, newfound species of ancient salamander received a digital makeover after researchers used X-ray images to create a 3D model of the animal's skull, which had been trapped in a rock for more than 50 years.

The ancient lizard, named Mamorerpeton wakei, dates to around 166 million years ago, during the Jurassic period (201.3 million to 145 million years ago). Based on its bones, it was likely an aquatic species that swam around ancient ponds and lakes, slurping up smaller creatures with powerful suction.

The oddly shaped fossilized skull is trapped inside a rock that was unearthed at a fossil site on Scotland's Isle of Skye in the 1970s. Paleontologists at the time deemed it less important than other fossils and placed it in storage; they didn’t attempt to painstakingly excavate any potential bones from the rock. However, advancements in scanning technology meant that a new team of researchers could see inside the rock without having to crack it open.

Read more: Stunning reconstruction of Jurassic salamander fossil reveals skull’s weirdness in 3D

Oldest flowering plant

Researchers in China unearthed a 164 million-year-old fossilized plant with a perfectly preserved flower bud, making it the earliest example of a flowering plant ever uncovered.

The fossil is around 1.7 inches (4.2 centimeters) long and 0.8 inches (2 cm) wide. It contains a stem, a leafy branch, a bulbous fruit and a tiny flower bud around 3 square millimeters in size.

Until now, fossil evidence had suggested that flowering plants didn't emerge until the Cretaceous period, but the new discovery pushes the emergence of the group firmly back into the Jurassic period. The new species was named Florigerminis jurassica.

Read more: 164 million-year-old plant fossil is the oldest example of a flowering bud

Mangled "dragon" fossils

Researchers proposed that a group of bizarre, mangled fossils in Ireland were likely deformed when ancient continents collided to form the supercontinent Pangaea.

The fossils belong to an extinct genus of small, amphibian-like tetrapods with dragon-like horns known as Keraterpeton. The remains are misshapen and have largely been replaced by the surrounding coal. They date back to around 320 million years ago and were first uncovered in 1866. Until now, scientists assumed that the fossils had been warped and degraded by acidic soils.

But a new team of scientists that reanalyzed the remains found that tiny phosphate crystals within the mangled bones, known as apatite, only dated back to around 300 million years ago, when Pangaea was taking shape. The researchers think that the apatite comes from superheated fluids from below Earth's crust, which came to the surface during the continental collision and could have warped the bones out of shape.

Read more: Mangled 'dragon' fossils were cooked by ancient continents colliding to form Pangaea

Transylvanian turtle

A never-before-seen species of ancient turtle was identified from the remains of a 70 million-year-old fossilized shell unearthed in the Transylvania region of Romania.

The newfound species, named Dortoka vremiri, is a side-necked turtle, of which there are 16 living species. D. vremiri is closely related to another species of extinct side-necked turtle that dates back to around 57 million years ago. This suggests that the new species likely survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out around 75% of all life on Earth, including the non-avian dinosaurs.

Researchers suspect that the turtles lived in freshwater habitats on an ancient island, which likely sheltered them from the worst damage caused by the falling asteroid 66 million years ago.

Read more: Ancient Transylvanian turtle survived the extinction of the dinosaurs

Impeccably preserved fish

A farm in England was the unlikely source of a Jurassic jackpot: a treasure trove of 183 million-year-old fossils, including ichthyosaurs, squids and insects, as well as other ancient animals. But the standout specimen was a stunningly preserved 3D fish head.

The head, which belonged to a fish from an extinct genus of ray-finned fishes known as Pachycormus, included a number of rarely fossilized tissues, such as scales, teeth and an eye socket. Researchers were amazed by the detail and orientation of the fossil.

"Usually, with fossils, they're lying flat," Neville Hollingworth, a field geologist with the University of Birmingham who discovered the site with his wife, told Live Science. "But in this case, it was preserved in more than one dimension, and it looks like the fish is leaping out of the rock."

Read more: 'Never seen anything like it': Impeccably preserved Jurassic fish fossils found on UK farm

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus