In a 1st, scientists counted all 10,000 nerve fibers in the human clitoris

The clitoris contains thousands more touch-detecting nerve fibers than once thought.

The nerve that enables the human clitoris to detect pleasurable touch contains thousands more nerve fibers than once estimated — about 10,000, rather than 8,000. Medical researchers discovered this by doing something that had never been done before: They actually counted the fibers.

Previously, it was widely accepted that the clitoris contained about 8,000 nerve fibers, but the origins of this number are fuzzy, lead study author Dr. Blair Peters, an assistant professor of surgery in the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) School of Medicine, told Live Science.

"The 8,000 number, it wasn't even an actual scientific paper," he said. The number comes from a line in a book called "The Clitoris" (Warren H. Green, Inc., 1976) by physician Dr. Thomas P. Lowry and his then-wife Thea Snyder Lowry, in which the authors briefly mentioned a study of cow clitorises and extended its findings to people.

"It wasn't based on human data," Dr. Rachel Rubin, an assistant clinical professor of urology at Georgetown University and a urologist and sexual medicine specialist at a private practice in the D.C. area, told Live Science. The cow-derived stat has been cited many times without being fact-checked — until now.

Related: How many organs are in the human body?

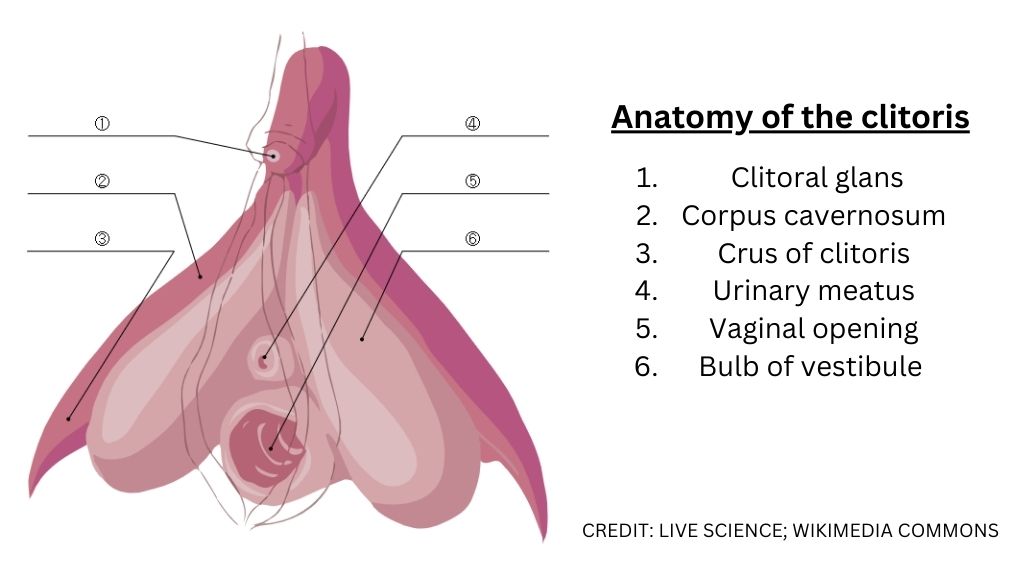

In their research, Peters and their colleagues examined the two dorsal nerves of the clitoris, which are dense bundles of nerve fibers that relay sensory signals from the clitoris to the brain. These nerves run down either side of the clitoral shaft and relay information about touch, pressure and pain, while other nerves handle functions like muscle tone and blood flow.

The sampled dorsal nerves contained between 4,926 and 5,543 nerve fibers each, or an average of 5,140 fibers. With two dorsal nerves per clitoris, that translates to about 10,280 nerve fibers that enable sensation in the pleasure-producing organ. These findings, which have not yet been peer-reviewed, were presented Oct. 27 at a joint scientific meeting of the Sexual Medicine Society of North America and the International Society for Sexual Medicine.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's remarkable, Peters said, is that these 10,000 fibers all plug into the clitoral glans, the visible portion of the clitoris located where the labia minora (inner lips) of the vulva meet. In comparison, the median nerve, which runs through the wrist and supplies sensation to most of the hand, contains 18,000 nerve fibers. When you compare the surface area of the clitoral glans to that of the hand, "10,000 compared to that 18,000 becomes shockingly high," he said.

Peters pursued this research, in part, to inform his work as a plastic and reconstructive surgeon specializing in gender-affirming surgeries, including gender-affirming phalloplasty, or the surgical construction of a penis from other tissues in the body.

To create a penis capable of erogenous sensation, surgeons take tissue from an area of the body with an ample supply of nerves, typically the forearm or thigh, according to the OHSU Transgender Health Program. Once the phallus is made, those nerves are then hooked up to nerves in the pelvis, and ideally, the nerves grow together and begin relaying sensory signals to the brain.

"I wanted to take a closer look, basically, at the nerves we connect when we make a penis," Peters told Live Science.

Broadly, research into the basic anatomy of the vulva, which includes the clitoris, could also aid in the diagnosis and treatment of nerve injury and help surgeons navigate procedures near the genitals without causing inadvertent damage.

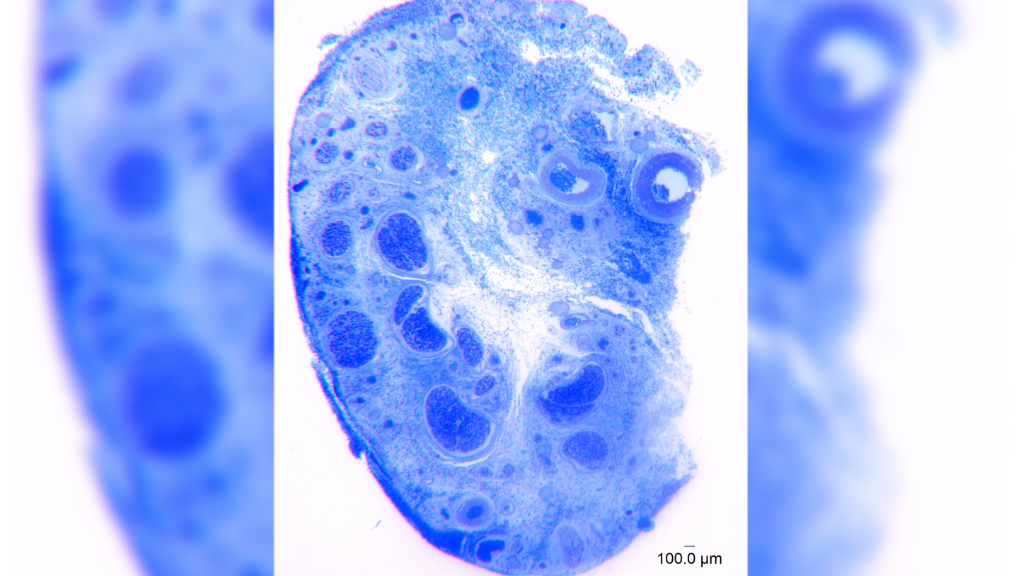

The new research was made possible by seven transmasculine patients who underwent phalloplasties and volunteered to donate samples of their clitoral tissue. These donated tissues were then preserved, stained blue and magnified 1,000 times under a microscope so that an image-analysis software could count individual nerve fibers.

All the patients underwent testosterone therapy prior to phalloplasty. There is some evidence that testosterone can boost nerve regeneration in the context of an injury, but in normal, healthy nerves, the hormone shouldn't change the number of fibers present, Peters said. "However, this study did not have controls without exposure to testosterone," they said, so it would be worth repeating the study with tissue samples from cisgender women who'd never had testosterone. Such samples would likely come from cadavers, rather than people undergoing surgery.

The new research highlights how little is known about the anatomy and function of the clitoris, Rubin said. This reflects historical biases in medical research that have left modern doctors with huge knowledge gaps. Rubin discussed these historic inequities in a New York Times investigation published in mid-October.

"It is likely that no doctor has ever examined your clitoris or asked about orgasm in a medical setting," she said. "And that's not because it's not worthwhile."

Editor's note: This story was updated on Nov. 9 to acknowledge a New York Times investigation on the same subject that heavily featured Rubin. The story was originally published on Nov. 1.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.