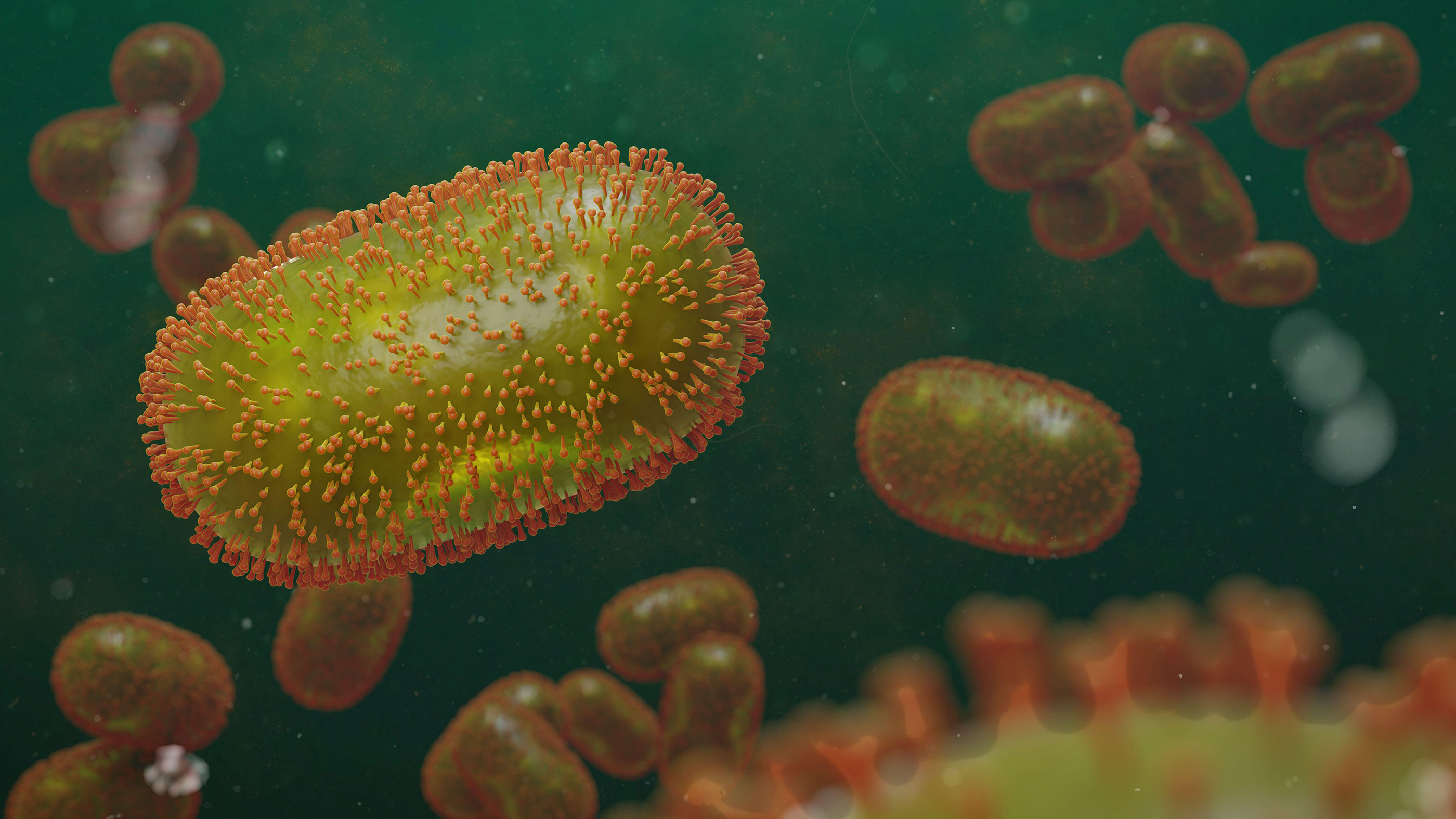

Monkeypox may have been spreading in UK for years

This is one hypothesis to explain the monkeypox strain currently spreading.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The monkeypox virus may have been spreading at low levels in the United Kingdom for years now, only becoming detectable in the last month, according to health officials.

This is the first time the smallpox-related virus has spread locally outside of West and Central Africa, where it is endemic, as all known past cases outside Africa were related to foreign travel. As of May 25, more than 200 people across 20 countries are confirmed to have monkeypox, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported. Currently, about 106 cases are people in the U.K., according to the U.K. Health Security Agency (UKHSA). The majority of cases worldwide have been identified in men who have sex in men, and officials have tentatively traced the origin of the current outbreak to two raves, one in Spain and the other in Belgium, according to news reports.

Officials are now suggesting the possibility that local transmission of monkeypox has been occurring in the U.K. for two to three years. For instance, four monkeypox cases were reported in the U.K. between 2018 and 2019 in individuals who had traveled to Nigeria; another three cases from similar travel were confirmed there in 2021, The Guardian reported.

Related: Monkeypox outbreaks: Here's everything you need to know

"It could hypothetically be that the virus transmission amplified from this low level of transmission when by chance it entered the population that is at present amplifying transmission," Dr. David Heymann, an infectious disease epidemiologist and WHO advisor, told The Guardian. Heymann said further study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The genetic sequences of samples of the monkeypox virus in this outbreak show it is most similar to the monkeypox strain that was reported in the U.K., Israel and Singapore (from African travel) in 2018 and 2019, The Guardian said. Mutations to the current strain could have arisen over time as the virus spread at low levels in the U.K.

For the virus to have picked up these mutations, it must have been spreading in several individuals. "We know that chronic infection is not a plausible scenario, and that means there has been a chain of transmission events that apparently went unnoticed," Dr. Marc Van Ranst, a virologist at the University of Leuven in Belgium, told The Guardian.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Monkeypox infections show up first with flu-like symptoms along with swollen lymph nodes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); one to three days after the fever begins, a person generally develops a rash that starts on the face and spreads across the body. That rash morphs into pus-filled "pimples" that scab over.

So how would such a visually apparent disease get overlooked?

"Between 2019 and 2020, if anybody came up with a rash in any part of Europe, you're not going to think of monkeypox, your thought would be other diseases that cause a rash," said Oyewale Tomori, a virologist and adviser to the Nigerian government, as reported by The Guardian.

If just a few cases are missed, those people can then spread the virus at a low rate to others, Tomori added.

Read the full story about monkeypox circulation in the U.K. at The Guardian.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus