The Milky Way is 'rippling' like a pond, and scientists may finally know why

Sagittarius just can't keep its hands off of us.

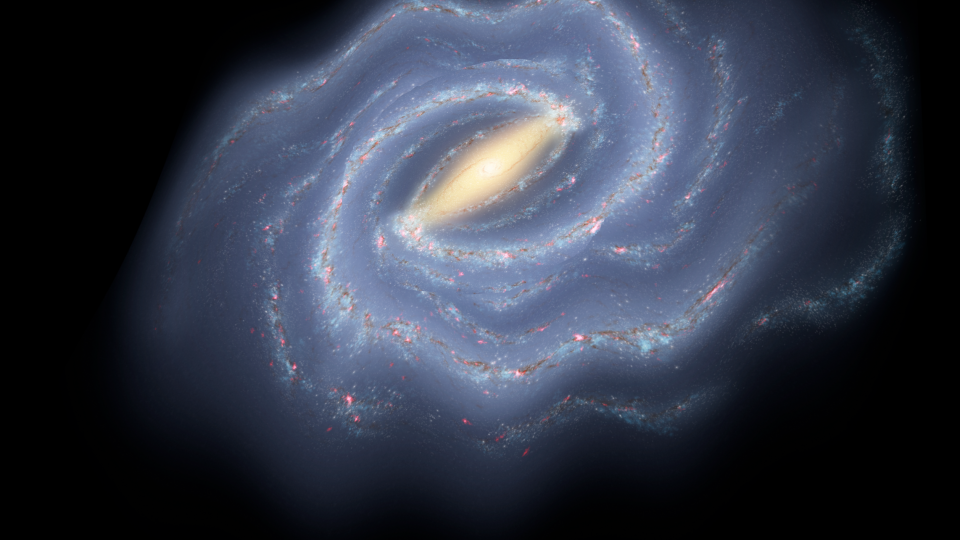

Imagine the Milky Way's 100 billion stars as a flat, tranquil pool of water. Now, picture someone dropping a stone the size of 400 million suns into that water. The tranquility is shattered. Wave after wave of energy ripples across the galaxy's surface, jostling and bouncing its stars in a chaotic dance that takes eons to calm.

Astronomers suspect that something like this may have really happened — not just once, but several times over the past several billion years.

In a new paper published Sept. 15 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers explain how a nearby mini-galaxy — the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy — appears to have crashed through the Milky Way on at least two separate occasions, causing stars all around the galaxy to mysteriously oscillate at different speeds.

Related: Largest galaxy ever discovered baffles scientists

Using data from the European Space Agency's Gaia space observatory, researchers compared the movements of more than 20 million stars located throughout the Milky Way, but particularly in the outer regions of the galaxy's disc. The data revealed a mysterious ripple, or vibration, that seemed to be jostling stars all throughout the galaxy.

"We can see that these stars wobble and move up and down at different speeds," study author Paul McMillan, an astronomer at Lund University in Sweden, said in a translated statement.

Through a process that the researchers equated to "galactic seismology," the team modeled a wave pattern that could explain the strange ripple effect setting the Milky Way's stars off-kilter. They concluded that the ripples were likely released hundreds of millions of years ago, when the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy last passed through our galaxy — "a little bit like when a stone is dropped into a pond," McMillan said. It seems likely that a second, even earlier collision between the two galaxies also occurred, the researchers added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Prior studies have suggested that an ancient collision with Sagittarius may have set off ripples at the Milky Way's center, but this new research is the first to show that those ripples extended all the way to the edge of the galaxy's disk, perturbing stars every step of the way. This new research should help piece together the long and violent history of our galaxy and its smaller neighbor, the researchers wrote.

Today, the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy is estimated to be about 400 times the mass of Earth's sun — a mere shrimp compared with the Milky Way's estimated mass of 1.5 trillion suns. Scientists suspect that Sagittarius was once much larger, but lost up to 20% of its mass to our galaxy after repeated collisions over the past several billion years.

These collisions likely changed the shape and size of our galaxy too; a 2011 study suggested that the Milky Way's spiral arm is the result of two collisions with the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. Another study of Gaia data released in 2020 suggested that cosmic crashes between our galaxy and Sagittarius triggered baby booms of new stars in the Milky Way every time the two galaxies met.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus