Rare Mercury Transit, the Last Until 2032, Thrills Skywatchers Around the World

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

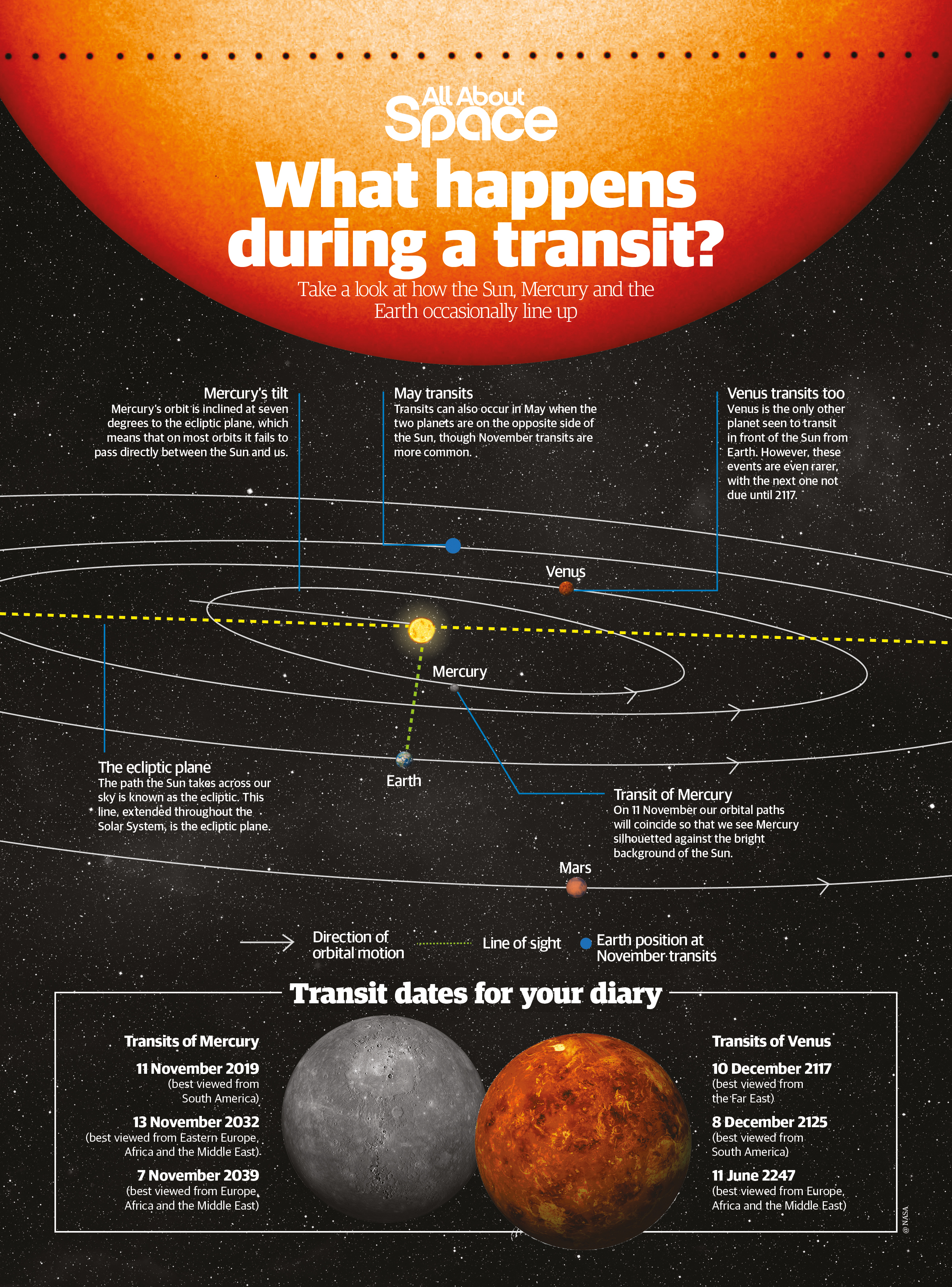

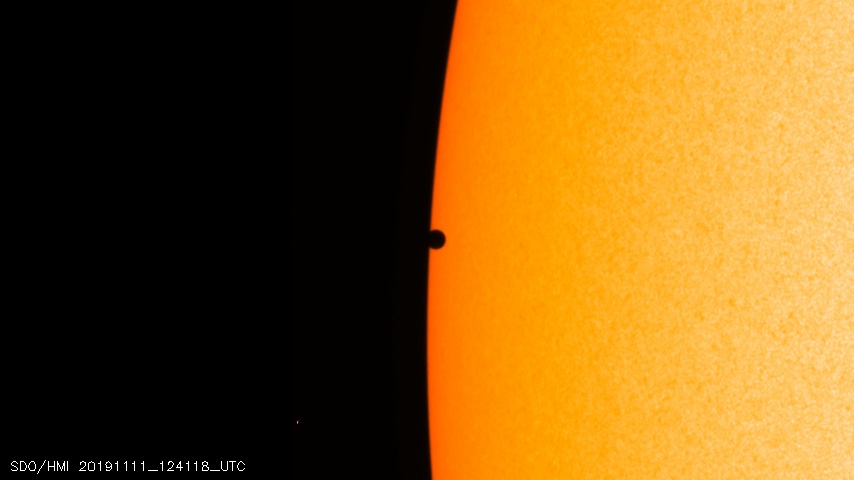

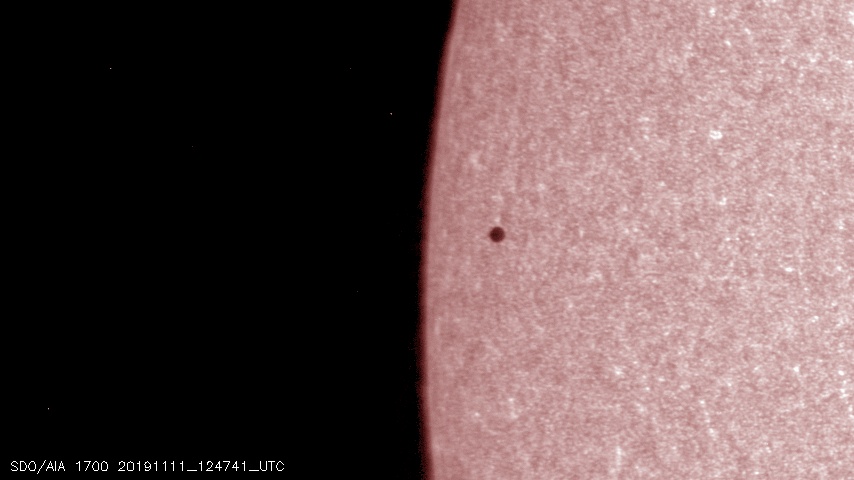

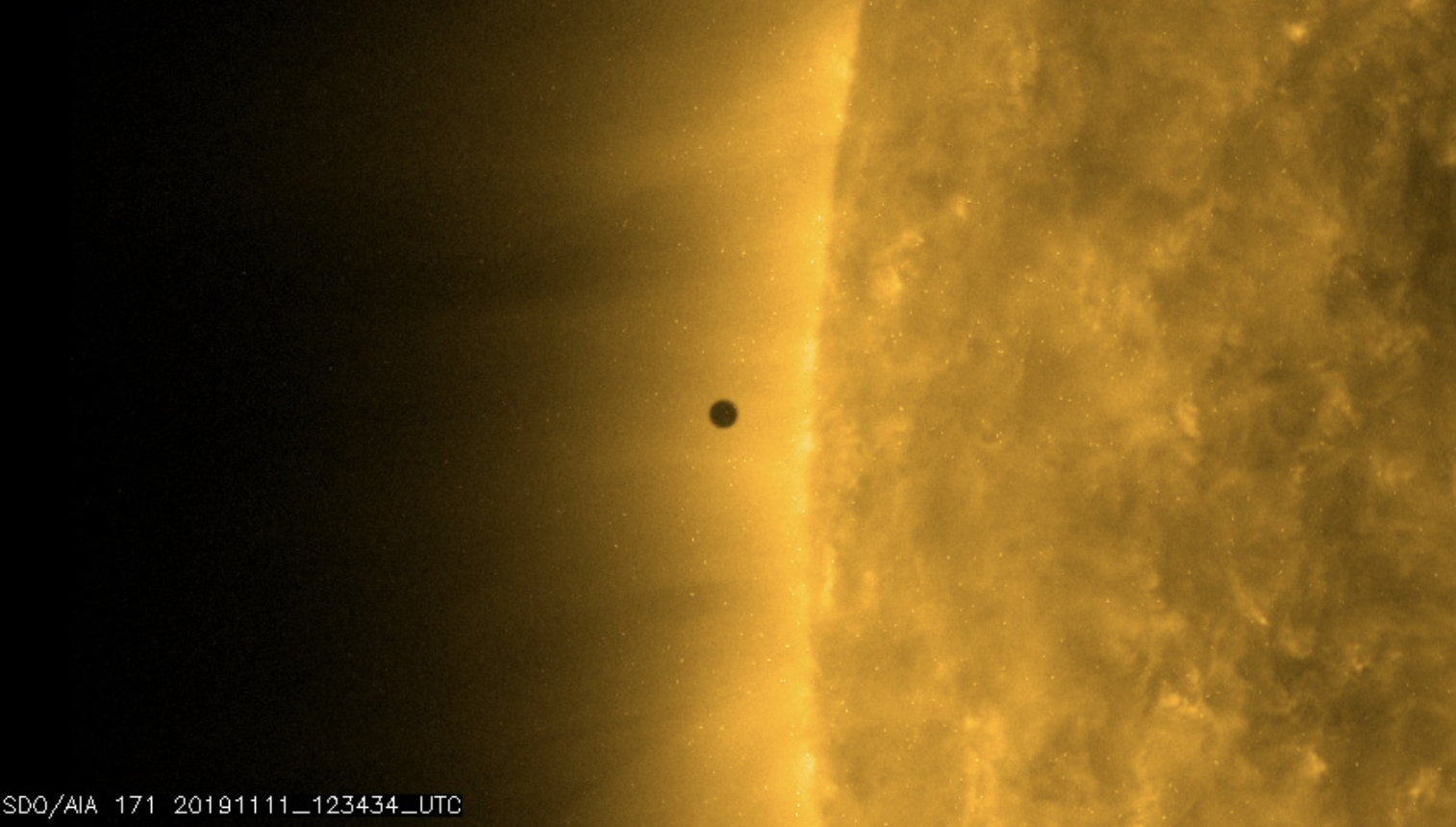

The tiny planet Mercury scooted across the sun's face today (Nov. 11) for the last time until 2032, and skywatchers around the world had the chance to witness the rare celestial event.

During this 2019 transit of Mercury, the innermost planet spent about 5.5 hours crossing in front of the sun from our perspective on Earth. Skywatchers across the Americas, Africa and Europe could see at least part of Mercury's journey across the sun, but only with telescopes or high-power binoculars equipped with protective solar filters. Meanwhile, several spacecraft, including NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, provided views of the event from space.

Mercury's silhouette began to encroach on the sun's disk at 7:35 a.m. EST (1235 GMT), when the sun was above the horizon for viewers in South America, eastern Central America and the U.S. East Coast. In the rest of the U.S., Mercury was already making its way across the sun by sunrise. In most of Africa and Europe, Mercury was still crossing the sun as the sun dipped below the western horizon.

Related: The Mercury Transit of 2019 in Photos! The Best Views Until 2032

More: Here's Why Mercury Transits Are So Rare

Mercury transit from Earth and space

While people on the ground carefully examined the sun and shared videos and photos on Twitter, astronomers shared their view of the action through sun-gazing telescopes. Technicians with NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory posted near real-time imagery and video of the Mercury transit in ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency’s Proba-2 mission was snapping images as well, according to an ESA tweet, although those photos haven't been released yet.

As of the final minutes of the transit, there was no word on whether the six astronauts on board the International Space Station would try to catch a glimpse of the transit. The Expedition 61 crew is equipped with astronomical observing equipment as well as cameras to catch celestial events, and they did gather footage during the 2017 solar eclipse.

On Twitter and in interviews, NASA and ESA used the opportunity to highlight current and upcoming missions to examine exoplanets and Mercury itself. NASA heliophysicist Alex Young told Space.com that the Mercury transit is similar to how the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) searches for exoplanets, as they travel across their parent stars.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ESA highlighted three of its missions on Twitter: BepiColombo en route to Mercury, the ESA Solar Orbiter that is getting ready for launch in 2020 to study the sun, and the Characterising Exoplanet Satellite (CHEOPS) that will also search for exoplanets using the transit method after its launch in December.

Transits of Mercury are relatively rare events, with about 13 happening every century, on average. The last Mercury transit was on May 9, 2016, and the next one will be on Nov. 13, 2032. Skywatchers in the U.S. won't get another Mercury transit until May 7, 2049.

How Mercury transits occur

Mercury and Venus are the only two planets that can transit the sun from Earth's perspective, because they are the only planets whose orbits are closer to the sun than Earth's. Venus last passed before the sun on June 6, 2012, and the next Venus transit isn't until Dec. 11, 2117. These transits happen because the planets' orbits are slightly tilted to the ecliptic, or the plane of Earth's orbit, and those orbits intersect at two places called "nodes." Transits occur when Earth crosses a node at the same time as the other planet. In Mercury's case, this always happens in May or November. For Venus, transits occur in June and December.

Amateur astronomers and astrophotographers around the world took heed of today's rare celestial treat and (weather permitting) captured some incredible images of Mercury as it inched across the sun like a tiny, traveling ink blot. With an apparent diameter of 10 arc seconds, Mercury's width was about 0.5% that of the sun. In terms of area, the tiny planet covered only 0.003% of the sun's disk. To see the little fleck on the sun, observers had to use magnifying equipment with special solar filters; it was too small to see with solar eclipse glasses.

Though the Mercury transit was not visible everywhere in the world — like Asia, Australia and Alaska, where it happened at night — anyone with an internet connection could still follow the event live online, thanks to astronomy webcast services like Slooh and the Virtual Telescope Project. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory also provided near-real-time views of the sun from space. These telescopes offered some solace to viewers across the midwestern and northeastern U.S., where overcast skies made it difficult for many eager transit-watchers to get a good view of the sun.

While skywatchers across the globe celebrated the rare chance to see a Mercury transit today, scientists also took the opportunity to learn more about the innermost planet — particularly its thin atmosphere. When Mercury passes in front of the sun, scientists can observe changes in sunlight that passes through its tenuous atmosphere, allowing them to study its elemental composition.

Waiting for 2032

It will be 13 years before Mercury transits the sun again and 30 years until it happens again in the U.S. — but if you got special gear to watch this transit safely, don't ditch those solar filters just yet! You can use the same solar filtered-telescopes and binoculars to watch some solar eclipses before the next transit, so long as the filters are not damaged.

Solar eclipses, when the moon blocks at least a portion of the sun's disk, occur about two to five times per year, with total solar eclipses — when the moon completely blocks the sun from view — occurring about once every 18 months, on average. To find out when the next solar eclipse will be visible near you, check out this handy list of eclipses with interactive maps from timeanddate.com.

Editor's note: If you captured an amazing photo of the Mercury transit, or any other celestial sight, and you'd like to share it with us and our partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments in to Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

- Mercury Transit 2019: The Astronomical History of This Rare Celestial Event

- Venus Crosses the Sun for Last Time Until 2117, Skywatchers Rejoice

- How to Catch the Next Eclipse: A List of Solar and Lunar Eclipses in 2020 and Beyond

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Hanneke Weitering is an editor at Liv Science's sister site Space.com with 10 years of experience in science journalism. She has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus