King Solomon's mines were abandoned and became a desert wasteland. Here's why.

Copper mines may have inspired legends about King Solomon.

Copper mines in Israel's Negev Desert — ancient sites that may have inspired the legend of King Solomon's mines of gold — were abandoned 3,000 years ago, when people there used up all the plants to make charcoal for smelting, a new study finds.

The researchers studied fragments of charcoal from ancient furnaces in the Timna Valley near Eilat, where a prosperous copper industry thrived from the 11th to ninth centuries B.C.

They found that the quality of the wood used to make charcoal deteriorated over the roughly 250 years when the mines and smelters operated, as people there used up all the nearby white broom and acacia and started using wood of much lower quality, such as the trunks of palm trees.

By about 850 B.C. the copper industry had been abandoned, and the wasted desert that remained wouldn't be exploited again for a millennium.

Related: King Solomon's mines in Spain? Not likely, experts say.

"Over time, they're using less and less of the wood that they knew from the beginning was better," study lead author Mark Cavanagh, an archaeobotanist and a doctoral student at Tel Aviv University, told Live Science. "And it looks like they're gathering wood from farther and farther away."

Ancient industry

The Timna Valley was one of the first places in the ancient world where copper was made, Cavanagh said. The region is an extension of the Great African Rift, so many minerals made deep in Earth's crust are exposed near the surface, including copper ores, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some of the earliest evidence for smelting copper ore in the Timna Valley dates to about 7,500 years ago, during the Chalcolithic, or Copper-Stone period, at the end of the Neolithic, or New Stone Age. The secret of alloying tin to the copper to make hard-wearing bronze wouldn't be discovered for about another 1,000 years.

For the latest research, published Sept. 21 in the journal Scientific Reports, Cavanagh and his colleagues studied fragments of charcoal from a much later period: during the Iron Age about 3,000 years ago, when the copper industry at Timna was at its peak.

Wood was first burned in underground pits with only a small amount of air to make charcoal, which burned much hotter, and for longer, during the copper smelting process, Cavanagh said.

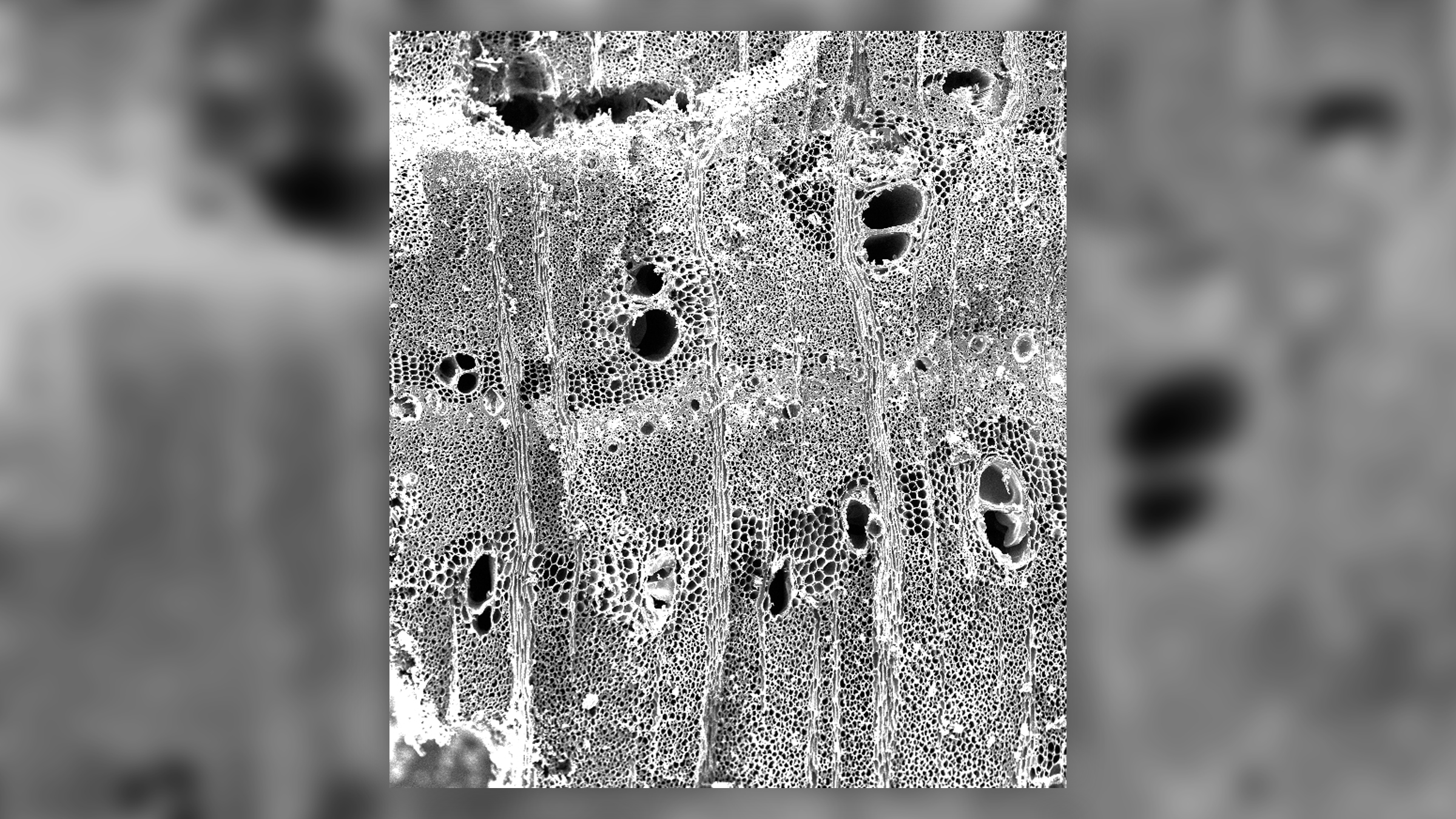

To determine which types of wood were used to make the charcoal, the researchers utilized an electron microscope to examine the slag left over from the smelting. Their analysis revealed the cell structures of the woods used, which showed that white broom and acacia were used extensively in the early phases of the copper industry at Timna but that much lower-quality wood was used later on.

Eventually, the mines were abandoned, possibly in part because it had become so hard to find good wood nearby, Cavanagh said. The copper industry at Timna wouldn't be restarted for about 1,000 years, when the Nabateans and then the Romans began importing better wood for charcoal.

King Solomon's mines

Cavanagh suggested that the hunt for wood to make charcoal in the Timna Valley contributed to the desert conditions there today, although it was a very dry environment to begin with.

"When you start cutting down the trees, you set in motion a snowball effect," he said. Fewer trees meant fewer animals and less water in the entire ecosystem, and "some of the things that disappeared have never returned."

Related: Could the Sahara ever be green again?

The period between the 11th and ninth centuries B.C. was when the biblical Israelite kings David and his son Solomon are thought to have ruled in Jerusalem, although some scholars now think David and Solomon may not have existed, according to historian Eric Cline of George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Cavanagh suggested that copper from the ancient industry at Timna might have given rise to the reputed wealth on display at Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem that was later interpreted by ancient writers as gold.

In 1885, Victorian writer H. Rider Haggard set his adventure novel "King Solomon's Mines" in South Central Africa, supposing them to be gold mines, and it's been made into movies, comics, and television and radio programs many times since. It's not clear if Haggard borrowed the myth of Solomon's gold mines or if he made it up.

Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, a professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University who isn't involved in the latest study, thinks David and Solomon were probably historical people who lived in about the 10th century B.C.

But he thinks their importance and the scale of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah that they ruled were greatly exaggerated in the Bible.

"Archaeology indicates that the territory ruled by David and Solomon was restricted, and it did not reach the copper sites in the south," he told Live Science in an email. "The first indication of the expansion of Judah into the arid zones in the south (and even then, not as far south as the copper sites) can be found in the 9th century — that is, a century after David and Solomon."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus