Hubble spots most distant star ever seen, 28 billion light-years away

Astronomers nicknamed it "Earendel," from the Old English word for "morning star."

Hubble Space Telescope recently detected a star that is the most distant ever seen. Located 28 billion light-years from Earth, the ancient object — which could be a single star or a double-star system — may be up to 500 times more massive than our sun; it's also millions of times brighter than the sun and was born when the universe was young.

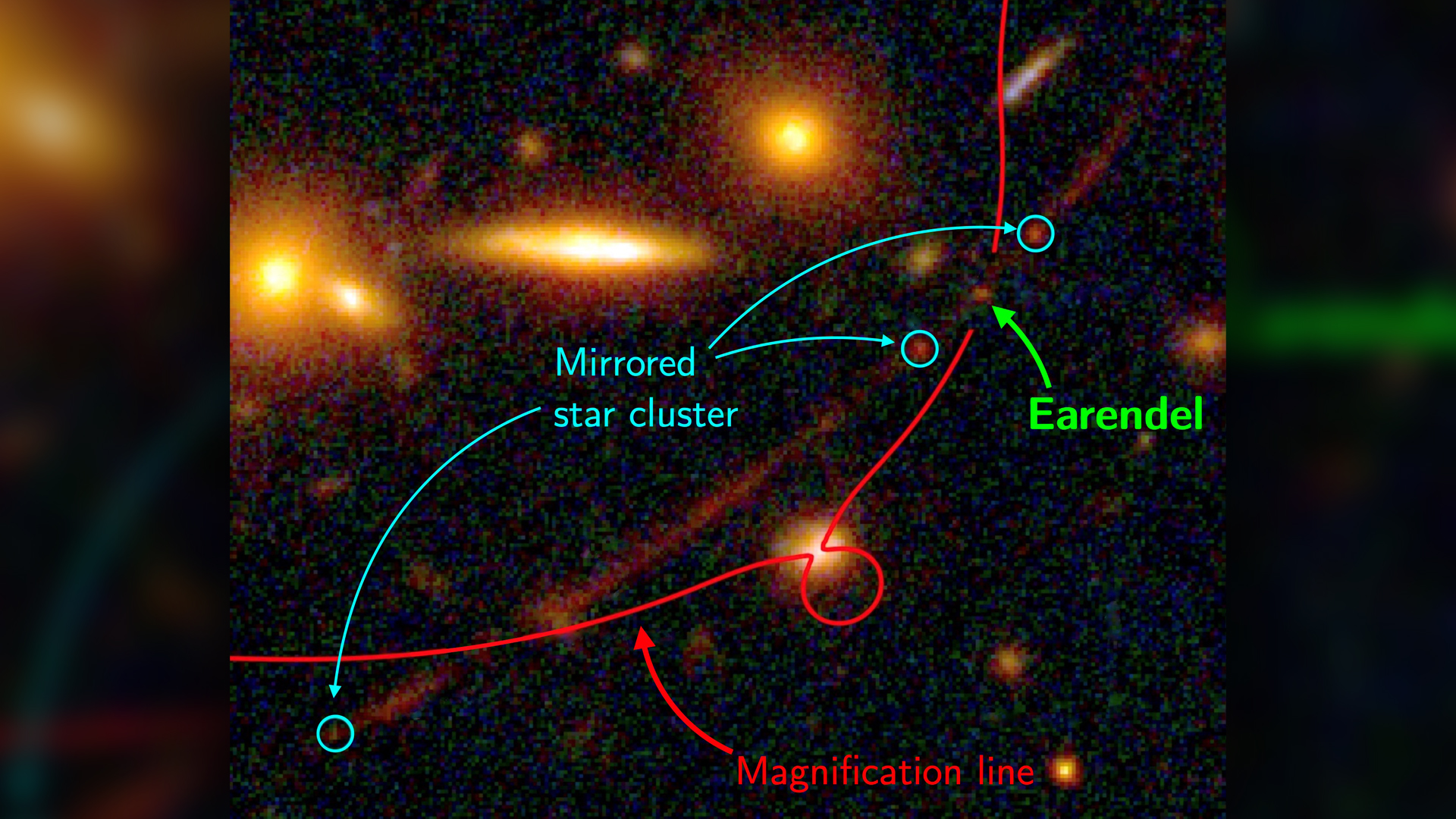

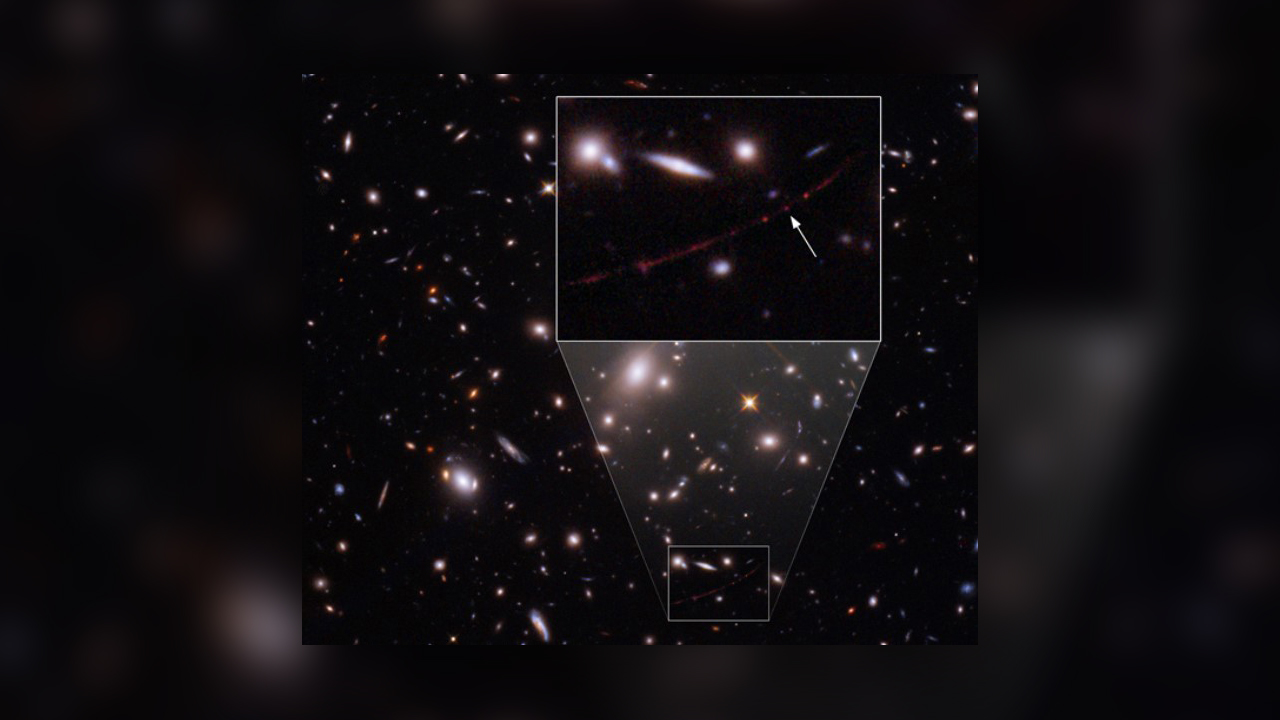

Hubble was able to spot the distant star during a nine-hour exposure because of the star's fortuitous alignment in the background of a cluster of galaxies. Gravity from the massive foreground galaxies warped space itself; this created an effect known as gravitational lensing that magnified the star's light tens of thousands of times, making it visible to Hubble's instruments, scientists reported on Wednesday (March 30) in the journal Nature.

The star's official name is WHL0137-LS, but the researchers nicknamed it "Earendel," from the Old English word for "rising light" or "morning star," according to the study. Follow-up imaging from Hubble confirmed that the star's appearance wasn't transitory — it had persisted in that spot under high magnification for 3.5 years.

Radius constraints of the object that were generated by computer models suggested that it was a single star or a binary system, rather than a star cluster, according to the study. Distant Earendel dates to about 900 million years after the Big Bang, which could place it in the first generations of stars in the universe, the researchers wrote.

Related: 26 cosmic photos from the Hubble Space Telescope's Ultra Deep Field

"As we peer into the cosmos, we also look back in time, so these extreme high-resolution observations allow us to understand the building blocks of some of the very first galaxies," study co-author Victoria Strait, a postdoctoral scholar at the Cosmic Dawn Center in Copenhagen, said in a statement.

"When the light that we see from Earendel was emitted, the universe was less than a billion years old; only 6% of its current age," Strait said. "At that time it was 4 billion light-years away from the proto-Milky Way, but during the almost 13 billion years it took the light to reach us, the universe has expanded so that it is now a staggering 28 billion light-years away."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

New eyes in space

Hubble launched on April 24, 1990 after decades of planning and research. It offered unprecedented views of objects in space that reshaped how astrophysicists studied the cosmos, helping scientists to create a 3D map of dark matter, and to determine the age of the universe and its rate of expansion, according to Royal Museums Greenwich in London.

Other recent Hubble observations include a triple-galaxy merger; a space "sword" penetrating an enormous celestial "heart"; and a phenomenon known as an "Einstein Ring," in which two galaxies that are about 3.4 billion light-years from Earth bend light from a quasar — another galaxy with a supermassive black hole at the center — to create a ring of magnified light. Einstein never observed one of these rings, but in 1915 he predicted that they were possible. In his theory of general relativity, Einstein wrote that massive objects could warp the fabric of the universe, making light appear to bend, Live Science previously reported.

And after more than three decades in orbit, Hubble has a new neighbor keeping an eye on our cosmic neighborhood — and far beyond. Another powerful observatory recently blasted into space: the James Webb Space Telescope, which launched Dec. 25, 2021 and is now orbiting the sun at a point approximately 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. The newcomer has been in the works for more than a decade and is a joint project overseen by NASA in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Webb will use its enormous primary mirror to capture infrared views of some of the oldest, dimmest objects in space, such as the earliest stars and galaxies, according to NASA. And as there is still much to discover about the newfound faraway star, such as its mass, temperature and spectral classification, the researchers hope to obtain more precise data from upcoming observations with Webb, they wrote in the study.

"Webb will even allow us to measure its chemical composition," study co-author Sune Toft, leader of the Cosmic Dawn Center and a professor at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, said in the statement. "Potentially, Earendel could be the first known example of the universe's earliest generation of stars," Toft said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.