What makes something fireproof?

Why do some things burn easily and others don't?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On Dec. 30, 1903, a spark from a stage light set Chicago's Iroquois Theatre ablaze. "The stage and the curtain and the rest caught fire," said Bill Carroll, grandson of the theatre's co-owner and adjunct professor of chemistry at Indiana University Bloomington. "There were insufficient exits, and it was terrible." Over 600 people died in the disaster — the deadliest single-building fire in U.S. history.

Nowadays, this probably wouldn't happen, because many modern materials are less combustible than they used to be. But what makes certain materials fireproof?

The term "fireproof" is actually a misnomer, because almost anything containing carbon, if hot enough, can combust and catch fire. "Fire resistant" and "flame retardant" are more accurate terms, Carroll told Live Science. When used properly, these fire protective measures can interrupt the burning process. For instance, typical plastic is combustible because it has a lot of carbon and hydrogen available to fuel a fire. Gasoline also has carbon and hydrogen available — and it's volatile, so gasoline can evaporate easily, making it highly combustible.

Related: How do wildfires start?

In contrast, a fire resistant material is one that doesn't burn easily. One example of this is the artificial stone used in kitchen countertops, like the DuPont brand Corian. The plastic of a Corian countertop is filled with finely ground rocks made of hydrated aluminum oxide, a chemical compound that doesn't burn. These rocks lower the fuel value (the amount of carbon available for combustion) of the countertop, making it more fire resistant, Carroll said.

"The aluminum oxide brought water with it, so when you compounded the two together [the plastic and hydrated aluminum oxide], what you in essence had was rocks that on a microscopic basis were wet," he said. "And you had them in a plastic matrix, so it was really, really hard to get any heat generated from this."

Although the rock attracts and holds water molecules, it does not get wet enough to form a puddle. Water keeps the countertop cool and helps block heat from getting any fuel. If there were a heat source (for instance, a lit cigarette resting on a Corian countertop), it would need to boil away the water surrounding the aluminum oxide first in order to then heat up the fuel, or the plastic molecules, enough to burn. Moreover, countertops like Corian don't have much plastic — there's just enough to hold the rock together, Carroll said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

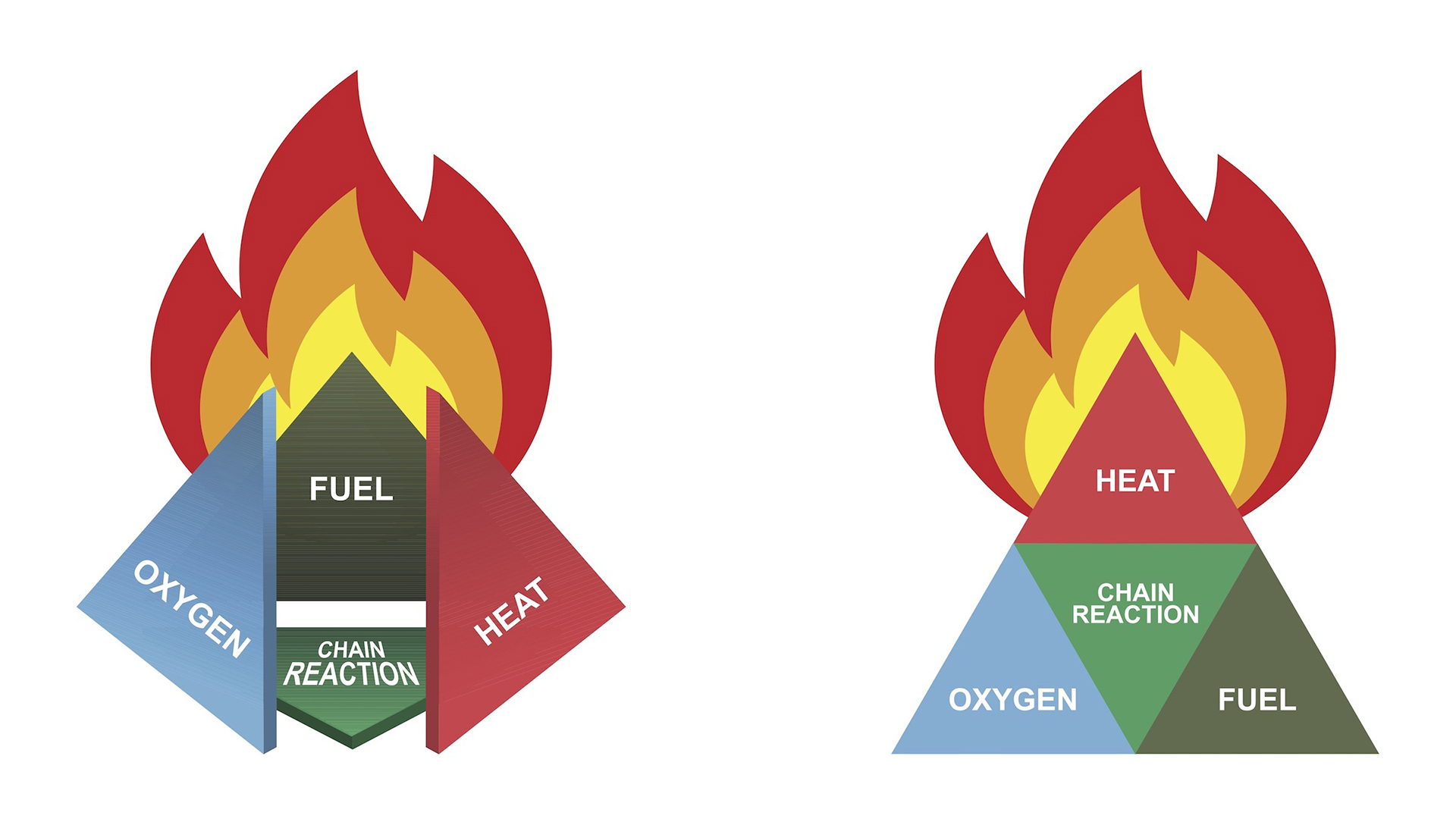

Fuel and heat are two sides of the fire tetrahedron, a triangular pyramid in which each side represents the elements necessary for fire. The other two sides are oxygen and a sustainable chemical reaction, Carroll explained. Most materials — aside from granite and asbestos, which are among the rare materials that are actually, literally fireproof — can be made more or less combustible only by eliminating one or more sides of the fire tetrahedron, he said.

Unlike fire resistance — the properties that make it hard for a fire to either start in the first place or keep going — chemicals known as flame retardants can help to slow or extinguish an already-burning fire. Chemical flame retardants contain chlorine, bromine, nitrogen, phosphorus, boron or metals.

Related: Can diamonds burn?

One way flame retardants work is through the formation of a substance known as char foam. When a piece of toast burns, for example, a char forms on the outside, which insulates the undamaged bread on the inside. Once a fire starts on an object treated with a char foam-inducing flame retardant, a chemical reaction within the retardant bubbles up to create a rigid, inflammable foam out of the char from the initial burning. This char foam then insulates the fuel from oxygen and, to some extent, heat, Carroll said. "[The char] kind of builds its own cocoon."

Flame retardant use has mushroomed since the 1970s, but it has sparked a controversy over the past few decades because of its potential toxicity. Brominated fire retardant chemicals, banned in the U.S. since 2004, worked well at putting out fires, but weren't permanently bound to the material, for example a mattress, Carroll said. That meant the chemical could potentially leave the mattress and end up in the dust or air, where it could be inhaled or ingested. That's cause for concern, because these chemicals are linked to a slew of health problems; for instance they might disrupt thyroid function, interrupt the immune system and increase cancer risk, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

"New strategies for making fire retardants [are] to either bind the chemical to the mattress or make it another polymer [a long, repeating molecule chain], another absolutely huge molecule that doesn't migrate," he told Live Science. In contrast, brominated fire retardants are smaller molecules that can easily leave materials and objects.

Can fire resistant materials and flame retardants be relied upon for fire safety? They do work well, but think of them as the second line of defense, Carroll said. Although it may seem like rather simple advice, keep fire, such as candles, out of bedrooms and carefully tend to stoves and other fire sources in the kitchen. "Don't have a fire where you don't want a fire in the first place," he said.

Editor's Note: This story was updated on Sept. 29 to change the word describing gasoline from "gaseous" to "volatile," or a substance that evaporates easily at room temperature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Dani Leviss is a freelance science writer and fact-checker based in New Jersey. She often covers water, animals, art, chemistry and technology. She has written for Scholastic, Hakai Magazine, IEEE Earthzine and News-O-Matic. Dani has a bachelor's degree in chemistry from Drew University in New Jersey. She also has a master's degree in science journalism from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus