Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Using a beam of radar less powerful than a microwave oven, researchers have produced the highest resolution images of the moon ever taken from Earth.

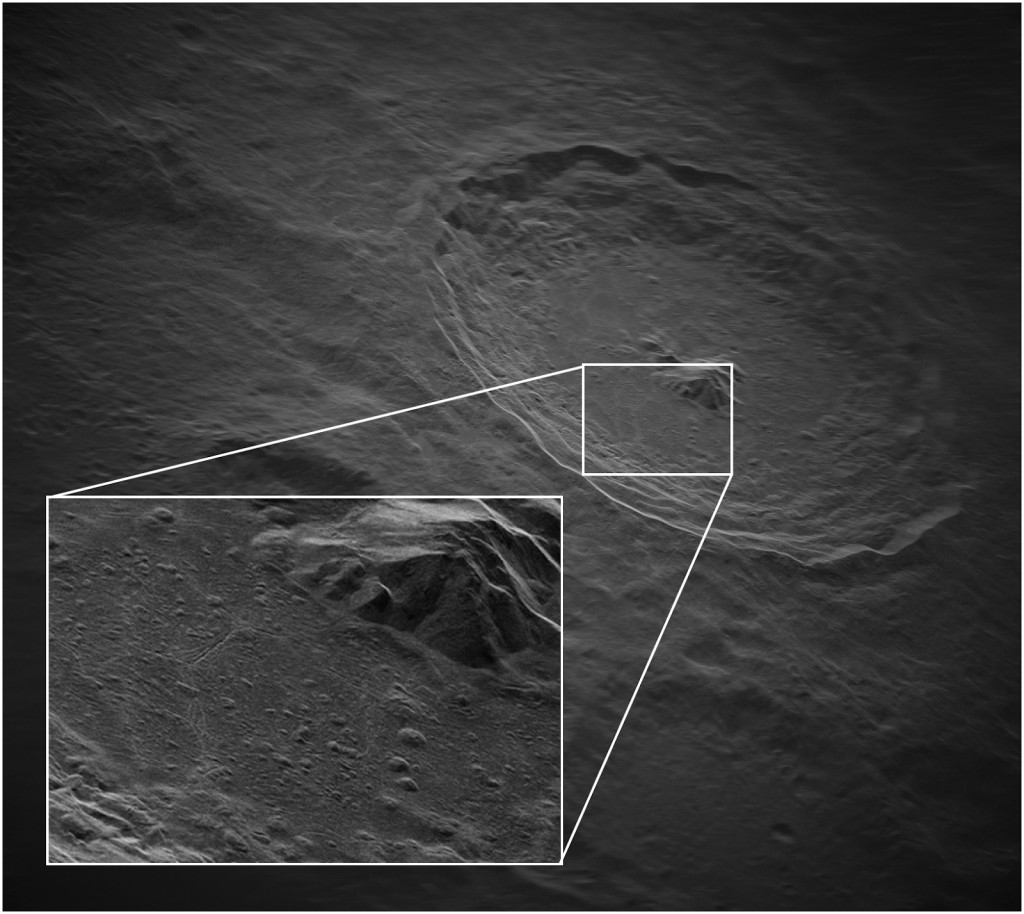

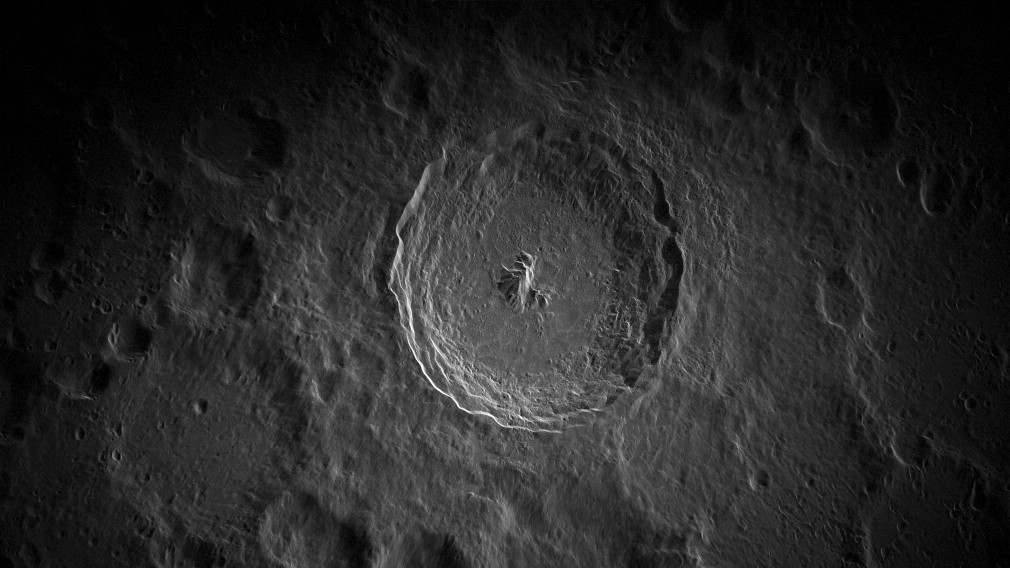

The stunning new pictures, presented Jan. 10 during a press conference at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Seattle, Washington, captured the landing site of NASA’s Apollo 15 mission as well as Tycho crater, a prominent impact feature in the southern lunar highlands.

Researchers made the images using the 330-foot-diameter (100 meters) Green Bank Telescope (GBT) in West Virginia — currently the world’s largest steerable radio telescope (a type of telescope designed so that its dish can be aimed at different parts of the sky), said Patrick Taylor, the radar division head for the Green Bank Observatory and National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), during the press briefing. The GBT shot out radio waves that illuminated the moon, and their echoes were captured by a set of four 82 feet wide (25 m) radio telescopes at the Very Long Baseline Array in Hilo, Hawaii, he added.

During the image capture, a prototype radar instrument on the GBT transmitted only 700 watts of power, “comparable to a household appliance or a bunch of light bulbs,” Taylor said. Yet it could spot features around the Apollo 15 landing site as small as 5 feet (1.5 m) and those in Tycho crater as small as 16 feet (5 m), he added.

Researchers also used the instrument to capture data about an asteroid roughly 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) across that zipped by our planet at more than five times the distance from Earth to the moon, Taylor said. Because of its size and orbit, the asteroid is characterized as potentially hazardous, but Taylor said that the object poses no risk to Earth at this time.

The instrument could not only see the asteroid but also characterize its size, speed, spin, composition and how light scatters off its surface, all with “something less powerful than your microwave,” Taylor said.

He and his team would like to develop a more advanced version of the same instrument that would be able to transmit with about 700 times more power, around 500 kilowatts. Such a system could be used to conduct geological studies of the moon and hunt for space debris around our natural satellite, as well as search for and characterize asteroids that may threaten our planet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This would enable the GBT to step in for the famous Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, which was previously the largest radio telescope used for similar purposes but collapsed in 2020.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus