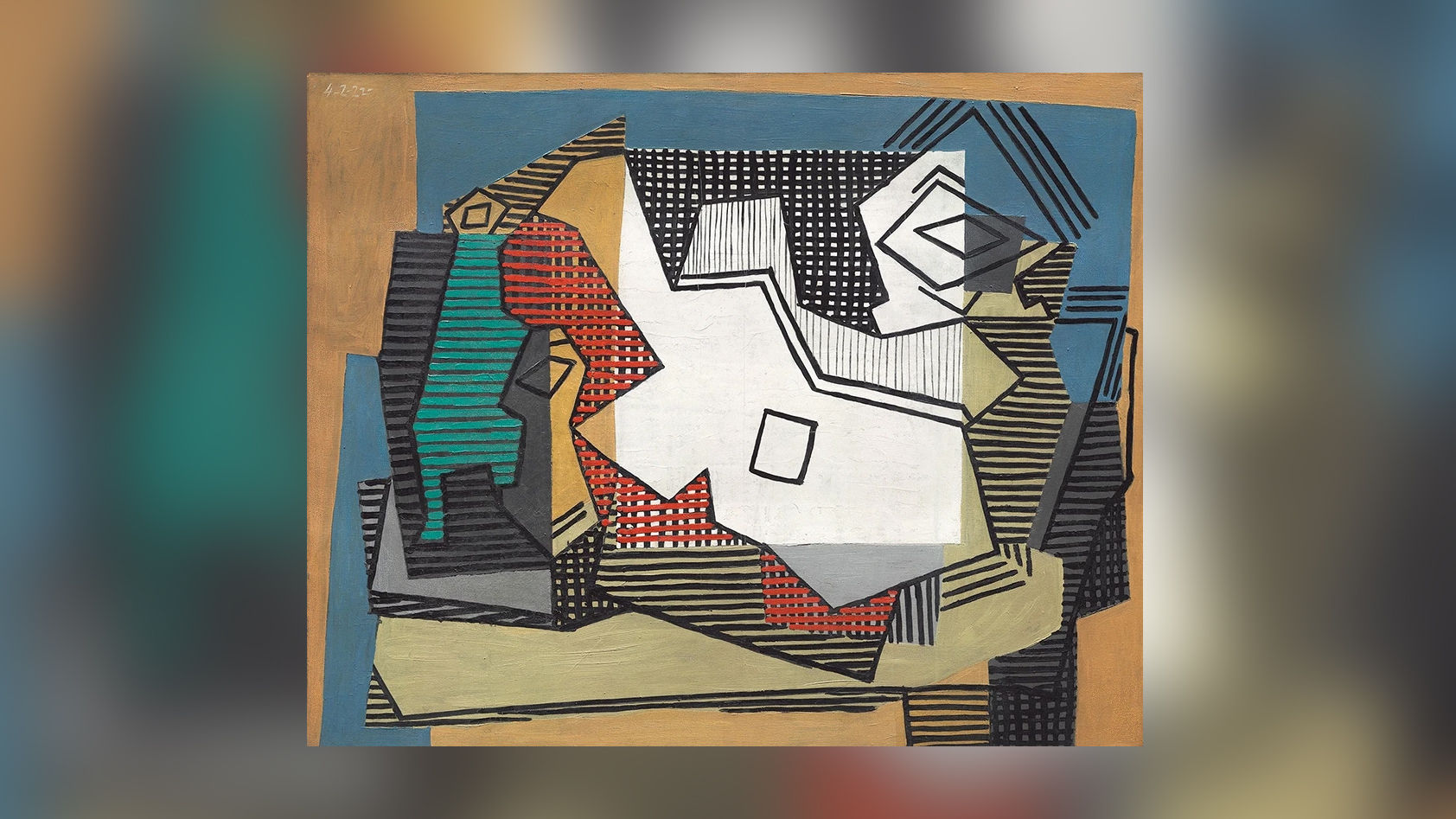

Picasso painting found hidden beneath his famous 'Still Life'

A hidden drawing by Pablo Picasso has been found beneath one of the artist's abstract paintings, called "Still Life."

A team from the Art Institute of Chicago was interested in looking more closely at the painting, which is held at the institute, to help understand its complex layers of paint and areas where the painting appears to be wrinkled. To do so, they used X-ray and infrared imaging, and to their surprise they saw a hidden drawing of "a pitcher, a mug, a rectangular object that may be a newspaper" propped up on what appears to be a tabletop or seat of a chair, the team wrote in a paper that was published July 21 in the journal SN Applied Sciences.

Related: 11 hidden secrets in famous works of art

It wasn't uncommon for Picasso to paint over previous works of art but usually he painted directly over them and incorporated the previous work into the new work, the team wrote. In this case, the team — Allison Langley, Kimberley Muir and Ken Sutherland — found that Picasso blocked out the newfound drawing using a "thick white layer" of paint before painting the abstract piece.

"This seems somewhat unusual in Picasso's practice, as he often painted directly over earlier compositions, allowing underlying forms to show through and influence the final painting," the team wrote in the paper.

As a result of Picasso's blocking method, "no evidence of the earlier composition" can be seen from the surface of the abstract painting. the team wrote.

They didn't speculate in their paper about why Picasso covered up the hidden drawing. The team is certain that the hidden drawing is Picasso's, noting that a similar work by the artist is now in the Gothenburg Museum of Art in Sweden.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The painting "Still Life" has a date on it saying Feb. 4, 1922 suggesting that it was painted about that time. Picasso gave it to Gertrude Stein, a "friend and collector of the artist and an important patron of modern art in early-twentieth-century Paris," the team wrote. He painted it during his so-called linear or Cubist phase, from late 1921 to 1922, in which the artist depicted 3D objects along different geometric planes and from different vantage points. The result was supposed to portray a painting that was closer to the mind's eye view.

In addition to revealing the hidden drawing, the imaging uncovered earlier attempts at conservation and restoration using an acrylic resin and a paint put into cracks in the surface. This aided modern-day conservation efforts, as the researchers were able to remove this resin and paint in the cracks to reveal the painting's original colors. Researchers from the team did not return requests for comment at press time.

The painting "Still Life" has a date on it saying Feb. 4, 1922, suggesting that it was painted about that time. Picasso gave it to Gertrude Stein, a "friend and collector of the artist and an important patron of modern art in early-twentieth-century Paris," the team wrote.

He painted it during his so-called linear or Cubist phase, from late 1921 to 1922, in which the artist depicted 3D objects along different geometric planes and from different vantage points. The result was supposed to portray a painting that was closer to the mind's eye view.

In addition to revealing the hidden drawing, the imaging uncovered earlier attempts at conservation and restoration using an acrylic resin and a paint put into cracks in the surface. This aided modern-day conservation efforts, as the researchers were able to remove this resin and paint in the cracks to reveal the painting's original colors. Researchers from the team did not return requests for comment at press time.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.