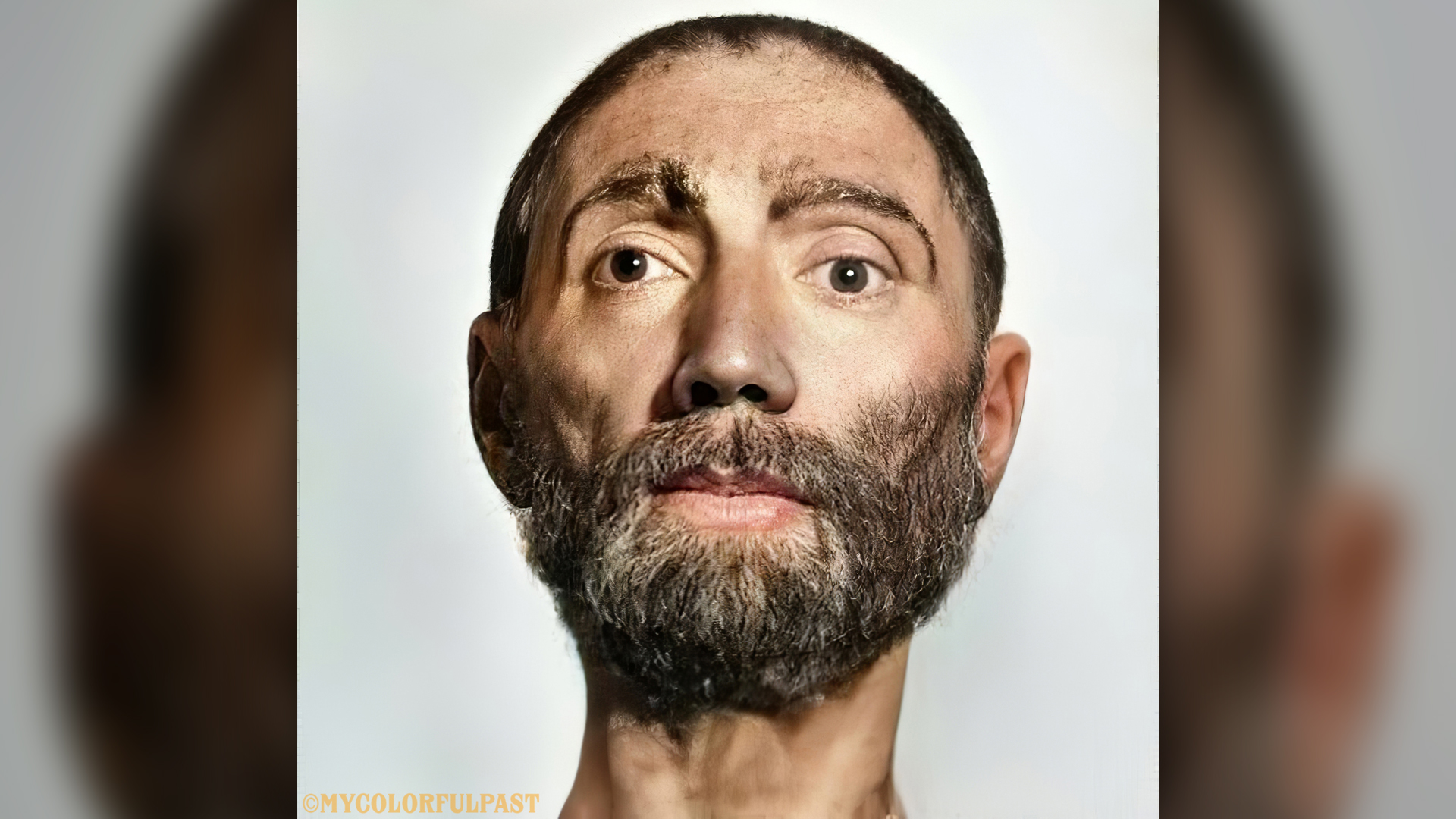

Death mask of King Henry VII is brought to astonishing life in a digital restoration

The king died in 1509 and is buried in Westminster Abbey

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The somber face of Britain's King Henry VII was recently given a digital makeover, in an astonishingly photorealistic reconstruction.

Graphic artist Matt Loughrey produced the image of the deceased king from Henry VII's death mask, which was cast in 1509. Loughrey is the founder of My Colorful Past, a project that restores and colorizes archival images of historic figures.

Long before the invention of photography, wax masks helped to preserve a person's likeness more accurately than paintings or illustrations did. Loughrey's restoration of Henry VII adds significant detail and natural colors to the molded mask impression, transporting a long-dead face from the distant past into the present.

Related: Photos: Lost Roman masks recreated

"It's the angle of his gaze — you can almost feel what he's thinking," Loughrey told Live Science. "We all want to look at faces and put a story behind them."

Henry VII ascended the throne in 1485, when he defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. When he died on April 21, 1509, at the age of 53, he had long suffered from asthma and gout, according to the website for Westminster Abbey, the royal church in London where British kings and queens are crowned, and where many (including Henry VII) are later entombed. The church's collection holds the head of the effigy that mourners carried at Henry VII's funeral; the effigy's face, which appears gaunt and careworn, is "particularly lifelike," and was probably made from his death mask, according to the Abbey.

Though the effigy was already lifelike, the new digital reconstruction is even more so. The project took about two months to complete and involved a combination of software, custom algorithms and meticulous image adjustments that were done manually, Loughrey said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shape, tone, lighting

The project began with a high-resolution image of Henry VII's wax death mask; Loughrey used photogrammetry — software that takes two-dimensional images and maps them in 3D — to then build a digital model of the king's face. "In photogrammetry, we can get a really good idea of positioning for the simpler things, like cheekbones, [eye] orbits, upper jaw," he explained. "The tonality of the skin is basically painting, it's all done by hand in layers."

Next came designing the lighting; "if the light is wrong or not in balance to the color of the flesh or the tonality, you see errors," Loughrey said. Finally, he added facial markings and hair, which he adjusted "using manual input and clever algorithms," he said.

Loughrey considered repairing flaws in Henry VII's mask — a wandering right eye and a poorly-painted right eyebrow, perhaps caused by damage that was later repaired. But in the end, he preserved them in his reconstruction, partly as a nod to the artists of the past and partly because "it gave the face more character," he said.

Henry VII's mask showed a clean-shaven face, but the king may have been shaved after his death so that the wax for the death mask could be more easily applied, as men during that era were commonly bearded.

"We'll never truly know if he was bearded or not," Loughrey said. "But considering the trends of the era, I did him with a beard, too."

Loughrey has also created facial reconstructions from the wax masks of figures such as Mary Queen of Scots, Oliver Cromwell and George Washington, to name a few. His digital restoration work also builds upon masks that are even older, such as the funerary masks that the ancient Egyptians created for mummified pharaohs like Tutankhamen.

"Death masks are like a conduit to another time — they're like a wormhole," Loughrey said. "Photography's been around for a very short time, but there's technology in place here that can take us back thousands of years, to see faces we've only imagined."

- Photos: See the ancient faces of a man-bun wearing bloke and a neanderthal woman

- Album: A new face for Ötzi the iceman mummy

- Photos: The reconstruction of teen who lived 9,000 years ago

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus