'Vampire' bacteria thirst for human blood — and cause deadly infections as they feed

Several bacteria that can cause deadly bloodstream infections in humans are attracted to an amino acid in our blood, scientists have discovered.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Vampires don't only haunt the pages of classic novels and spook us in horror movies — they're also lurking inside the human body.

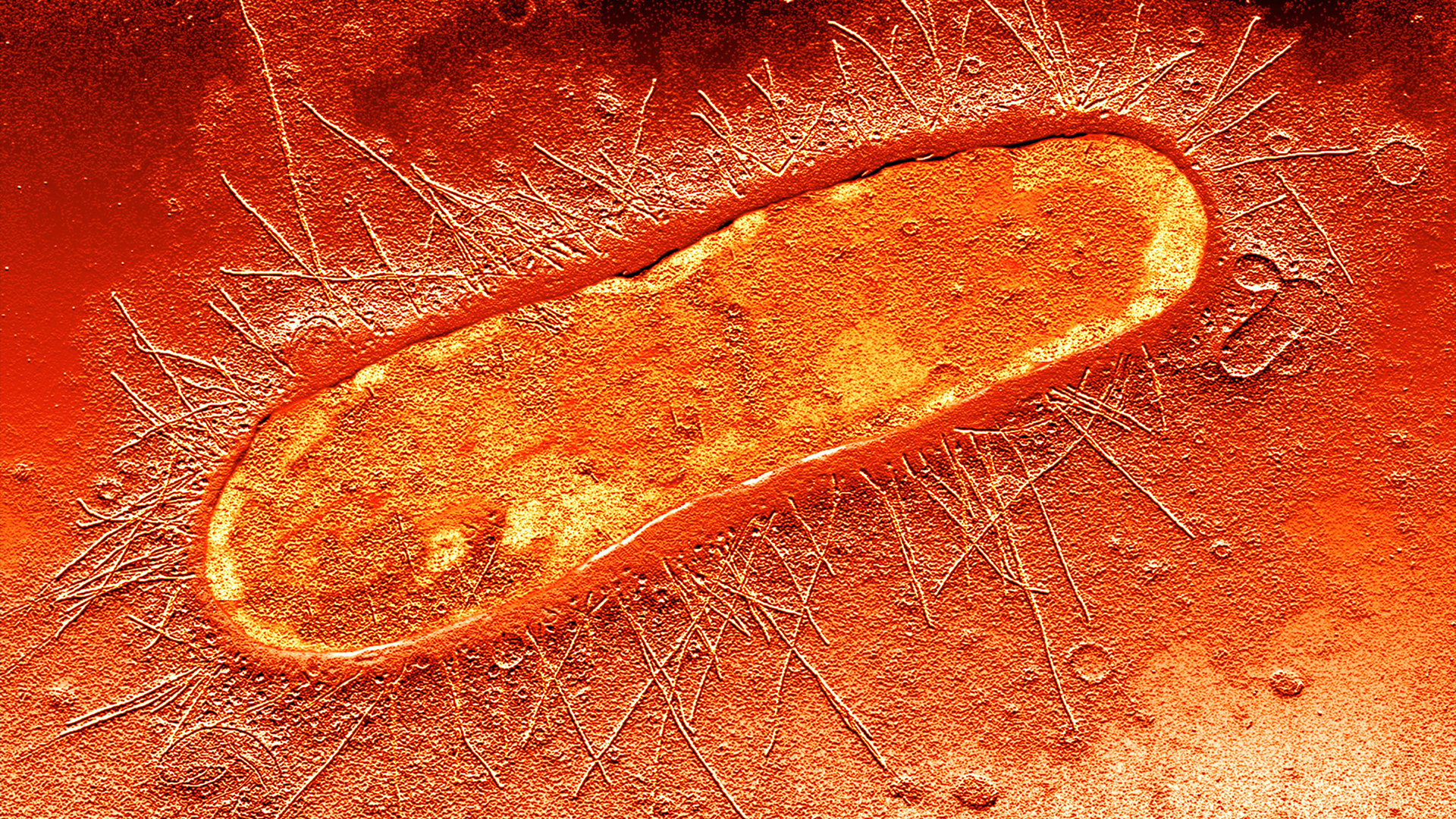

In new research, scientists have found that several bacteria responsible for life-threatening bloodstream infections enter our blood because they are attracted to the liquid, or serum, within it. This is most likely because human blood contains a molecule — the amino acid L-serine — that bacteria can use as food. The researchers behind the study have dubbed this phenomenon "bacterial vampirism."

The scientists focused on three species of bacteria commonly found in the human gut that belong to the Enterobacteriaceae family, called Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli and Citrobacter koseri. They found that all three species exhibit these vampire-like traits when exposed to serum sampled from humans.

Bacteria were already known to be attracted to L-serine; however, the new findings demonstrate how this response could specifically help disease-causing bacteria invade our blood.

Members of the Enterobacteriaceae family are commonly associated with bloodstream infections, which can lead to sepsis, or blood poisoning. Blood is normally sterile, meaning it's free of bacteria and other potential pathogens, so when bacteria end up in the blood it can be a big problem.

As many of these Enterobacteriaceae bacteria live in the intestines, people with conditions that hinder their intestinal immune defenses — such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — are at particularly high risk of developing bloodstream infections.

Related: Cholesterol-gobbling gut bacteria could protect against heart disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Until now, though, scientists didn't understand exactly why these bacteria are attracted to human blood. Uncovering their Dracula-like tendencies could therefore lead to new treatments for deadly bloodstream infections, say the authors of the new study, which was published Tuesday (April 16) in the journal eLife.

"By learning how these bacteria are able to detect sources of blood, in the future we could develop new drugs that block this ability," Siena Glenn, lead study author and postdoctoral student at Washington State University, said in a statement. In short, these drugs could be to bacterial vampires what garlic and crucifixes are to fictional vampires.

"These medicines could improve the lives and health of people with IBD who are at high risk for bloodstream infections," Glenn said.

In their study, Glenn and colleagues grew S. enterica, E. coli and C. koseri in petri dishes. They then introduced human serum onto these dishes, simulating how these bacteria may be exposed to human blood during intestinal bleeding, for instance.

The bacteria immediately responded to the serum, swimming toward its source within less than a minute. Using a high-resolution microscope, the team also discovered that the Salmonella bacteria possess a protein that interacts with L-serine in the serum.

This protein, a receptor called Tsr, is found across the whole Enterobacteriaceae family, suggesting that L-serine is a key chemical in blood that these bacteria sense.

"This study is interesting in that it firmly established that bacteria are attracted to human serum, most likely due to their attraction to the molecule L-serine, which is quite prevalent in serum," Navish Wadhwa, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and the Biodesign Center for Mechanisms of Evolution at Arizona State University, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

"While bacterial attraction to L-serine has been known at least since the 70s, this study places it in the context of host-bacterial interactions," Wadhwa said. It reveals how this sensing ability can specifically draw bacteria towards human blood.

Going forward, it would be valuable to see if and how other substances in blood, such as sugars and small molecules, might attract bacteria to human serum, he said. This could point to additional ways to prevent the blood-suckers from invading our veins.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus