'Parrot fever' outbreak in 5 European countries kills 5 people

Most people involved in the current parrot fever outbreak developed the disease after being exposed to infected wild or pet birds, the WHO said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An outbreak of a respiratory infection that most often affects birds has killed five people in Europe, the World Health Organization (WHO) warns.

During 2023 and the start of 2024, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands have reported an "unusual and unexpected increase" in cases of so-called parrot fever, beyond what's been seen in previous years, the WHO said in a statement Tuesday (March 5). In all, the illness has affected almost 90 people, with five deaths reported among them.

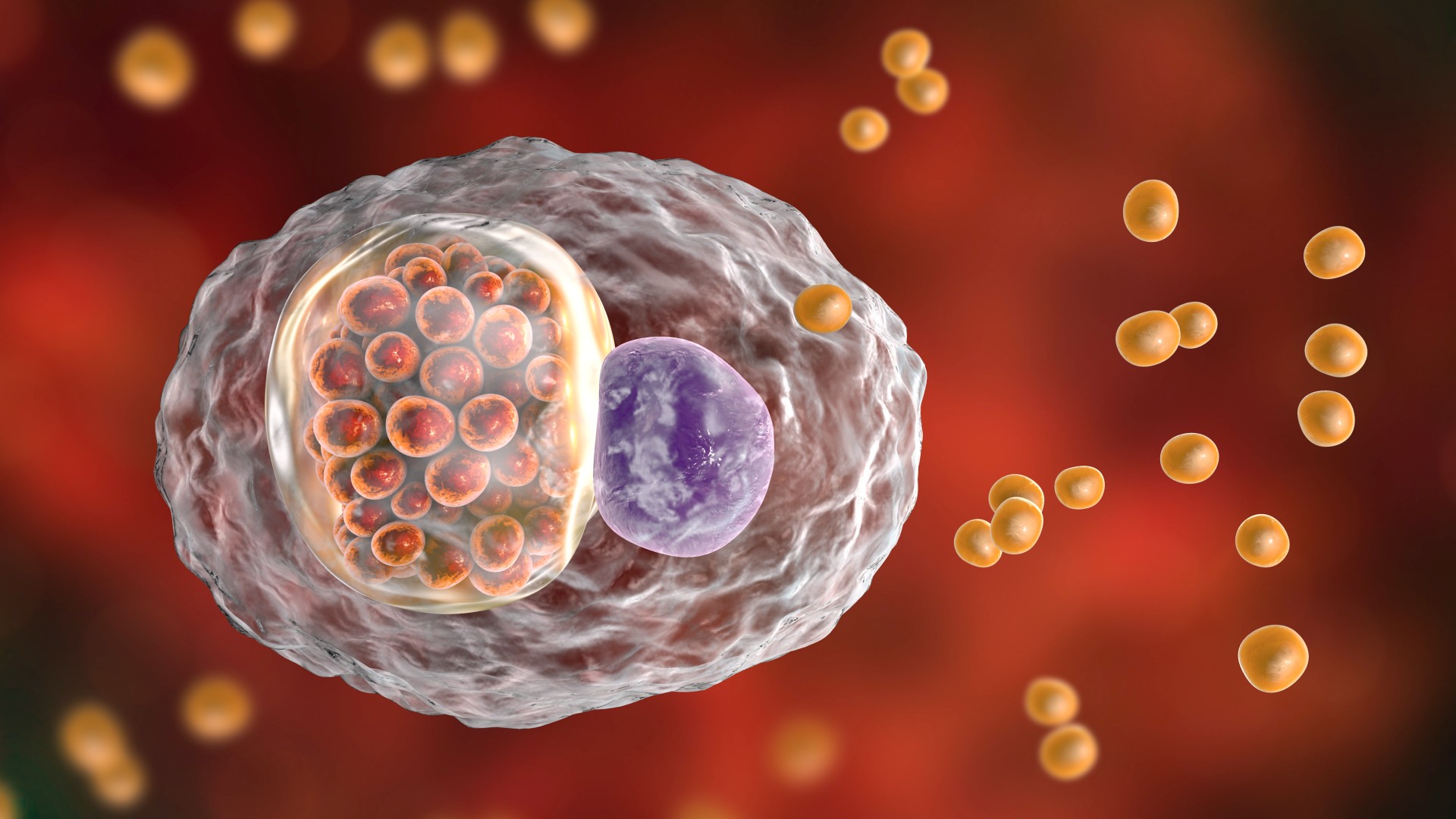

Parrot fever, or psittacosis, is caused by a species of bacteria called Chlamydia psittaci (also spelled Chlamydophila psittaci). The bacteria can infect many mammals — including dogs, cats and horses — but most often infects birds.

Humans can catch psittacosis by inhaling airborne particles containing C. psittaci, but human-to-human transmission of the disease is very rare, with only a handful of cases ever reported. Instead, most people develop psittacosis by inhaling particles that waft from the breath, poop or feather dust of infected birds, especially pets such as parrots, finches or canaries.

The disease is thus more common in people who come into close contact with birds — such as poultry workers, veterinarians and pet-bird owners.

That said, C. psittaci infection is possible without having direct contact with birds, and there's no evidence that the bacteria can be spread by preparing or eating poultry.

Related: Scientists release genetically modified mosquitoes to fight dengue in Brazil

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Psittacosis typically causes mild illness in humans. Its symptoms resemble those of the flu — such as fever, chills, headache and dry cough — and usually appear within five to 14 days after a person is exposed to the bacteria. Antibiotics effectively cure the disease if they're used early in the course of infection, and they help prevent serious complications, such as pneumonia and inflammation of the heart.

Appropriate treatment with antibiotics can reduce the death rate of psittacosis from between 15% and 20% to just 1%.

The five countries affected by the current psittacosis uptick have reported far more cases than usual. Some of these cases were suspected, based on symptoms, and others were confirmed with various diagnostic tests. Notably, most cases involved contact with infected wild or pet birds. But in some cases, recent contact with birds wasn't reported at all.

Austria, for instance, usually has around two human psittacosis cases a year. But in 2023, 14 were reported, and four more occurred between Jan. 1 and March 4, 2024. These cases were unrelated, and none of the patients had traveled abroad or had contact with wild birds.

In recent years, Denmark has usually had 15 to 30 psittacosis cases annually. However, from late 2023 to late February 2024, around 23 people have been infected. Of these cases, 17 people were hospitalized, 15 developed pneumonia and four died. One case was linked to an infected pet bird. Of the 15 other cases with available information, 12 had direct contact with wild birds, mainly via bird feeders, while four said they'd had no contact with birds.

Germany normally has around 15 cases a year but saw 19 in 2023 and early 2024. Eighteen of the 19 cases resulted in pneumonia, with 16 people hospitalized due to their infection. In the Netherlands, 21 people got psittacosis between December 2023 and late February 2024 — twice as many as did in the same period in prior years. Everyone was hospitalized, and one person died. Thirteen had contact with either wild or pet bird droppings, and eight had no contact with birds.

Sweden saw 26 cases of psittacosis in November and December 2023 — double the number seen in the same period in previous years. But complicating the picture, the country then saw a lower-than-average total of 13 cases in January and February 2024.

Further investigation is needed to determine whether the increase in cases across countries is really because more people are developing the disease, or rather that more cases are being detected thanks to improved surveillance and diagnostic techniques, the WHO said.

Nevertheless, "the concerned countries have implemented epidemiological investigations to identify potential exposures and clusters of cases," the WHO said. Samples from wild birds that have been submitted to the lab to test for avian influenza, or bird flu, are also being analyzed for signs of C. psittaci infection.

There's no indication that psittacosis is being spread by humans within these countries or internationally, and the risk of human-to-human transmission is low, the WHO said. In the meantime, the organization advises pet-bird owners to keep their animals' cages clean, avoid overcrowding their pets, and wash their hands when handling the birds or their poop. Newly acquired birds should also be quarantined when first brought home and taken to the vet if ill.

Psittacosis symptoms in birds include poor appetite, a ruffled appearance and eye or nose discharge. Death rates vary by species but can be 50% or more in parrots, for instance.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus