Pig kidney transplanted into human patient for 1st time ever

Doctors in Boston performed the first pig kidney transplant in a living patient.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A man in Massachusetts just became the first person to receive a pig kidney transplant.

Scientists have been developing genetically engineered pigs as a way to address the critical lack of human organs available for transplant surgeries. Several proof-of-concept experiments with such pig organs have been done in recent years; one involved hooking a kidney up to a brain-dead organ donor's body, and another involved performing a double-kidney transplant in a brain-dead patient. In addition, in 2022, a man underwent the first pig-heart transplant but died shortly thereafter.

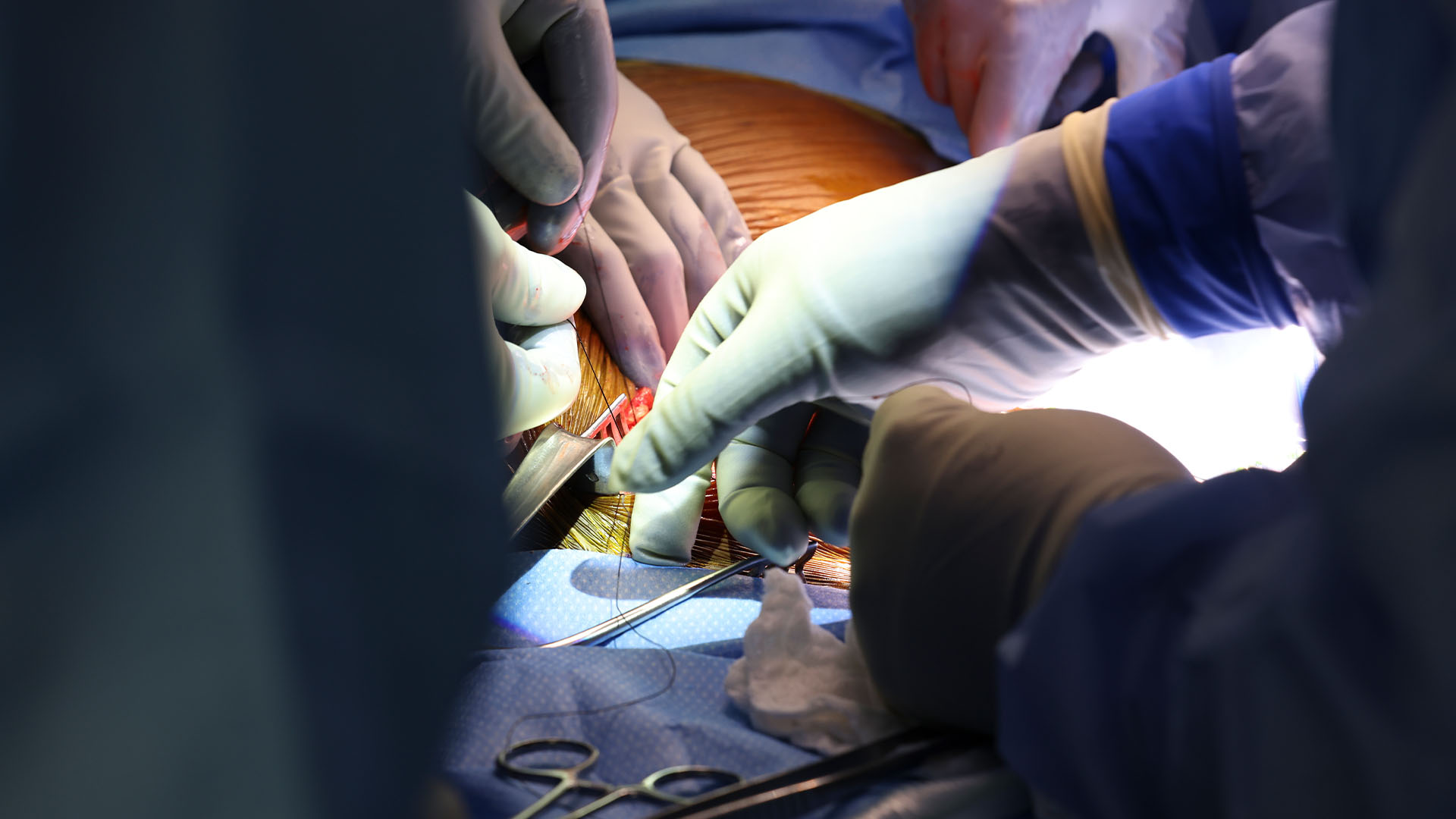

In this latest medical milestone, surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital transplanted a pig kidney into a living human patient for the first time. The 62-year-old patient, Richard Slayman, is recovering well after his four-hour surgery on March 16, and he's expected to be discharged from Mass General soon, according to a statement from the hospital.

"I saw it not only as a way to help me, but a way to provide hope for the thousands of people who need a transplant to survive," Slayman said in the statement.

Related: What happens to your body when you're an organ donor?

Slayman, from Weymouth, Massachusetts, has a history of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure and had been on dialysis for seven years before undergoing a human kidney transplant in 2018. However, five years later, the transplanted organ showed signs of failure. He restarted dialysis in 2023, which caused serious complications that required regular hospital visits to manage.

"He would have had to wait five to six years for a human kidney. He would not have been able to survive it," Dr. Winfred Williams, associate chief of the nephrology division at Mass General and the patient's primary kidney doctor, told The New York Times.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An opportunity arose for Slayman to receive a pig kidney, and after discussing the procedure's potential risks with his doctors, he consented to the operation.

The kidney itself came from eGenesis, a biotechnology company that's developing human-compatible engineered organs. The company uses the famous gene-editing system CRISPR to tweak the genes of its pigs.

To make the organs suitable for people, the scientists snip out three genes involved in making carbohydrates, or sugars, found in pigs that the human immune system attacks. In addition, they add seven human genes that help prevent immune-related domino effects that could lead to transplant rejection. And finally, they disable snippets of viral DNA — called endogenous retroviruses — in pigs' genomes that don't bother the pigs but can hurt humans, according to eGenesis.

In all, the scientists make 69 edits in the pig DNA, CNN reported.

As part of the transplant procedure, Slayman received two antibody-based treatments to help prevent organ rejection, as well as immune-suppressing drugs. The apparent success of the procedure raises the hope that such transplants could one day be common.

"Our hope is that dialysis will become obsolete," Dr. Leonardo Riella, medical director of kidney transplantation at Mass General, told The Washington Post.

Slayman's surgery "also represents a potential breakthrough in solving one of the more intractable problems in our field, that being unequal access for ethnic minority patients to the opportunity for kidney transplants due to the extreme donor organ shortage and other system-based barriers," Williams added in the hospital's statement.

"An abundant supply of organs resulting from this technological advance may go far to finally achieve health equity and offer the best solution to kidney failure — a well-functioning kidney — to all patients in need," he said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus