'Sex drive switch' discovered in male mouse brain that kicks their libido into overdrive

In a mouse study, scientists identified a collection of neurons that regulate sexual behavior in males, and they think humans may have a similar circuit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists may have uncovered the brain's "on switch" for male libido, a new study in mice suggests.

The switch is actually more of a circuit, consisting of a group of neurons that connects multiple regions of the brain. The newly identified circuit not only helps male mice recognize females but also controls their desire to have sex with them, complete the act itself and experience pleasure as a result, the study suggests.

The authors say the findings, published Friday (Aug. 11) in the journal Cell, may improve our understanding of how sexual behaviors are regulated differently in male and female mammals. Someday, the work could lead to the development of new drugs to treat low libido, which is estimated to affect 1 in 5 men at some point in their lives. Although maintaining a high sex drive is not essential for one's health, the sudden, unexpected loss of libido can be distressing to both individuals and their sexual partners.

"If these centers exist in humans — and now we know where to look — it should be possible to design small molecules that can be used to regulate these circuits," lead study author Nirao Shah, a professor of psychiatry and neurobiology at Stanford University, said in a statement.

Related: Why do guys get sleepy after sex?

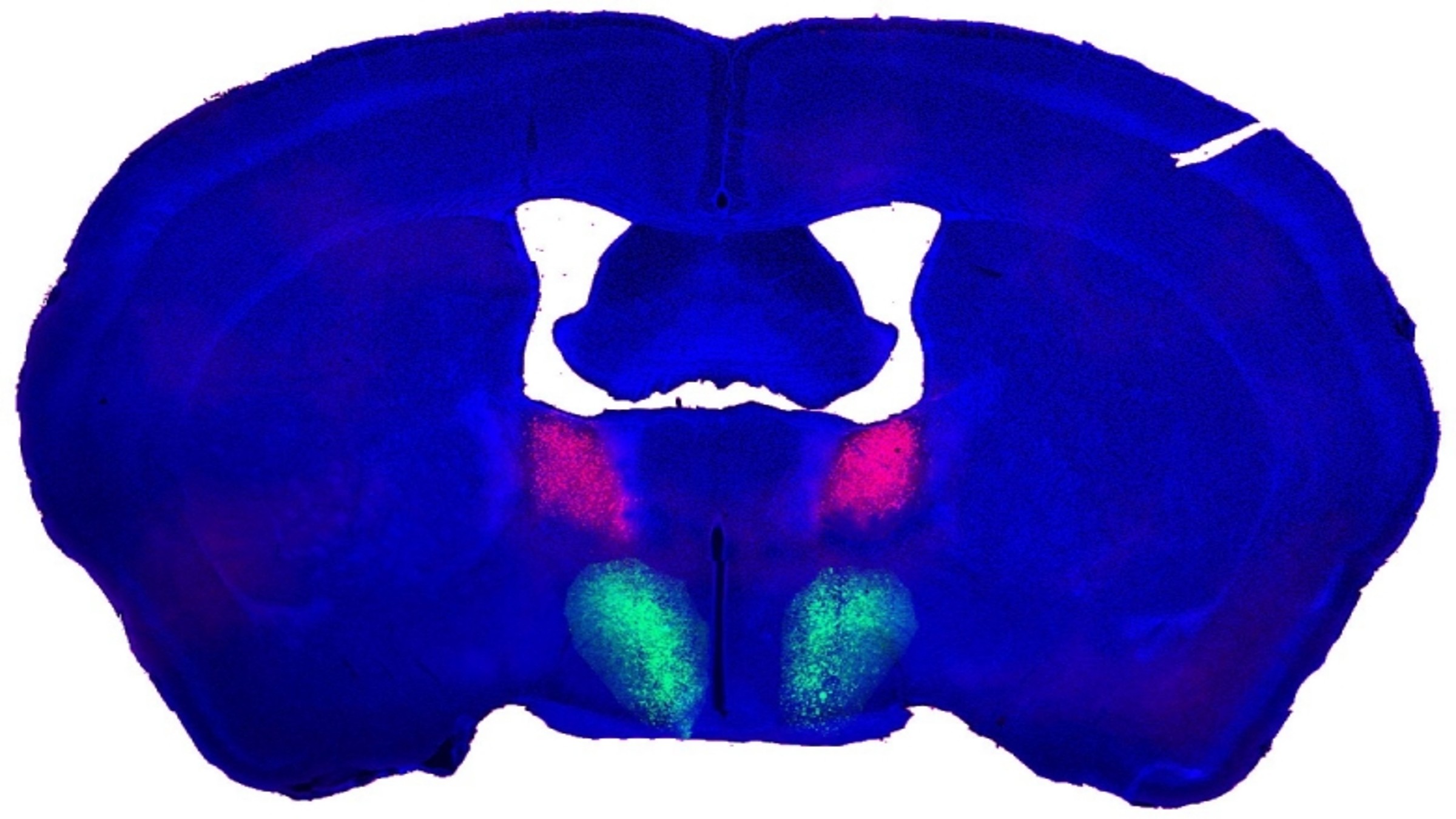

In the new study, researchers looked at the brains of adult virgin male mice who hadn't seen a female mouse since they were weaned. Previous research by the group had pinpointed a group of neurons that regulate whether male mice can identify the sex of female mice on sight. These neurons connect two regions of the brain: the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) in the amygdala, a key brain region for emotional processing, and the preoptic area of the hypothalamus (POA). Having revealed the importance of these cells, the team decided to explore exactly how they communicate.

The team found that certain neurons in the BNST secrete a chemical known as substance P. The small molecule binds to receptors on specific POA neurons, which subsequently activate and shoot messages to regions of the brain that respectively regulate movement and the experience and anticipation of feelings of pleasure associated with sex.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the researchers stimulated these BNST neurons in male lab mice, the rodents' POA neurons became increasingly more active and they began having sex with the female mice after a 10-to-15-minute delay. Directly activating the mice's substance P-sensitive POA neurons boosted the rodents' sex drives so much that they attempted to mate with inanimate objects.

What's more, by stimulating the rodents' POA neurons, the researchers dramatically cut the break time male mice normally take between rounds of sex. Instead of taking about five days to recover their sex drive after ejaculation, the mice needed only a second or less to be ready to have sex again. Conversely, when the team stopped these POA neurons from working, the mice lost all interest in mating.

Shah's team is still working to identify a similar circuit in female mice, but in the meantime, they're confident that a human equivalent of the male mouse libido circuit will be identified. "It's very likely there are similar sets of neurons in the human hypothalamus that regulate sexual reward, behavior and gratification," he said in the statement.

Shah added that any future drugs that target this circuit would work very differently to the likes of Viagra, which treats erectile dysfunction by increasing blood flow to the penis. Instead, the drugs would directly amplify or reduce the activity of a specific area in the brain that controls male sexual desire, he said. This could help treat either low or high sex drives by ramping up or turning down the circuit's activity.

However, such drugs are a long way from reaching the market.

"Regulating libido is enormously complex in humans with lots of social, political, ethical and other considerations that need to be addressed prior to thinking about any such approach," Shah told HealthDay.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Aug. 17, 2023 to correct the description of one of the mouse experiments.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus