Menstrual cycle linked to structural changes across whole brain

A study of 30 women with regular menstrual cycles suggests that the structure of the brain fluctuates in time with hormonal shifts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hormones that fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle might change the brain's structure, a new study suggests.

The study, conducted by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), reveals subtle changes in the brain structure of 30 women throughout their menstrual cycles. These changes matched up with fluctuations in four hormones.

Importantly, we don't yet know whether or how these brain changes affect cognition or the risk of brain diseases. But the research builds on a growing number of studies showing the effects that hormones associated with the menstrual cycle can have on the brain. More broadly, it bolsters the number of studies focused specifically on people who menstruate.

"Most of what we know about the human body is from studies that were carried out primarily on the male body," said Viktoriya Babenko, a former doctoral student at UCSB, current research specialist at BIOPAC Systems and co-first author of the study, which was posted Oct. 10 to the preprint database bioRxiv and has not yet been peer-reviewed. The other first author was Elizabeth Rizor, a current doctoral candidate in the dynamical neuroscience program at UCSB.

Related: Pregnancy causes dramatic changes in the brain, study confirms

The researchers gathered data from 30 women who were not taking hormonal birth control and had regular monthly periods. The researchers took images of the women's brains at three points during their menstrual cycles: menstruation, ovulation and the mid-luteal phase, which leads up to menstruation and is often associated with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms.

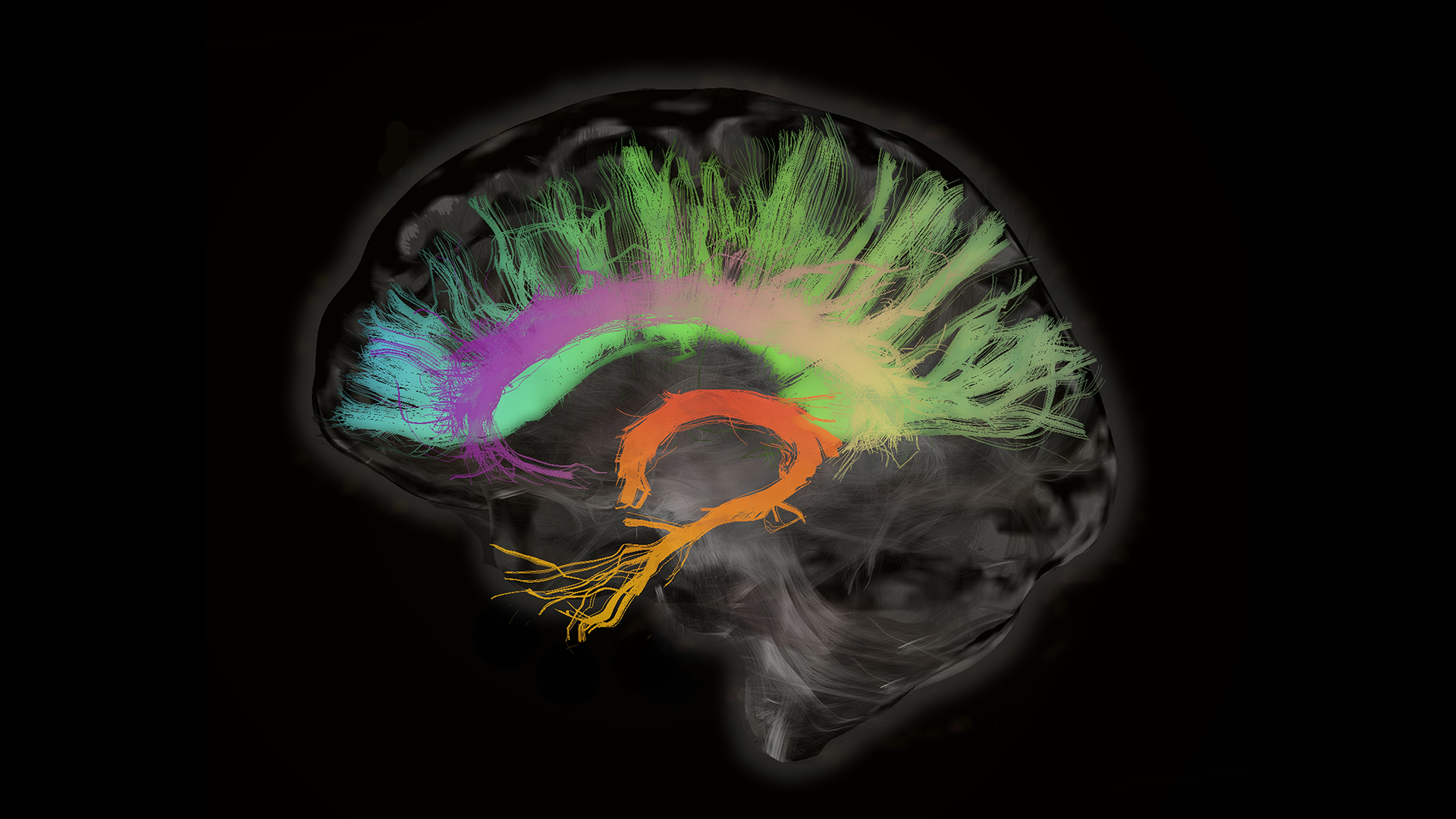

The researchers collected data related to brain volume and to two different types of brain tissue: gray matter, which contains the main bodies of brain cells; and white matter, which connects and enables communication between the cells. They measured cortical thickness, or the thickness of the brain's wrinkled outer layer, which is made of gray matter, and they collected data related to how water diffused across the brain's white matter.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This examination of water diffusion "allows us to have a better understanding about how white-matter fibers are structured," Erika Comasco, an associate professor of molecular psychiatry at Uppsala University in Sweden who was not involved with the study, told Live Science.

While probing the brain's structure, the study also looked at changes in four hormones throughout the menstrual cycle: estradiol (a type of estrogen), progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Estrogen and LH levels peak during ovulation, while progesterone peaks during the luteal phase. FSH, in contrast, stays more consistent but also peaks during ovulation, as well as reaching relatively high levels at the end of the luteal phase and during menses.

Across the brain regions the team looked at, estrogen and LH concentrations were correlated with the efficiency of the diffusion of water across white matter. This reflects changes in the white matter's "microstructure" that some scientists think reflect changes in connectivity, but that's somewhat debated.

Meanwhile, FSH concentration was correlated with cortical thickness — so, as it waxed and waned, so did the gray matter of the cortex. Interestingly, in several brain regions, FSH and progesterone seemed to have opposite associations with diffusion and cortical thickness — increases in FSH matched up with less-freely diffusing water and greater cortical thickness, while increases in progesterone were tied to the opposite patterns.

Although the brain's overall volume stayed the same, increases in progesterone were associated with increases in brain tissue volume but decreases in cerebrospinal fluid, the fluid surrounding the brain that protects it and helps it remove waste.

This study isn't the first to examine changes in brain structure throughout the menstrual cycle, but it is notable in that it examines tissues across the whole brain. Other studies have used different measures to record these changes; for example, a recent study published in the journal Nature Mental Health used high-resolution MRI scans to identify volume differences in several brain regions across the menstrual cycle.

One limitation of the study was that the scans taken at different points in each participant's cycle may not have been perfectly timed, particularly for ovulation and the mid-luteal phase. To determine these phases, participants used an ovulation test, which can have some variation. Collecting data at more points during the menstrual cycle would have added detail to the study. Another limitation is that all of the participants were younger than 30; the associations the researchers found might be different for older people.

Though the study could have included more people, Rizor and Babenko said the size was typical or even larger than average for an imaging study of this type, especially considering that they collected data from each person at three different times.

Future work could focus on how these changes affect a person's mental health throughout the menstrual cycle or the risk of conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, which is more common in women than in men. Other research could examine how these changes might affect behavior, which the recent study did not investigate.

"It's basically an anatomic study," said Dr. Sarah Berga, a professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University at Buffalo, who was not involved in the study. "But you know, we can't do everything in one study."

Rizor said she hopes the research will someday help medical professionals better incorporate the wide-ranging impacts of the menstrual cycle into medical care.

"The medical world should take note of how significant these fluctuations are in our day-to-day lives and incorporate them more into care," she told Live Science.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others, or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus