Green comet C/2022 E3 will make its closest approach to Earth in 50,000 years this week. Here's how to watch.

The green comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) will make a close approach to Earth on Feb. 1 before sailing off into deep space, possibly never to return.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On Feb. 1, a bright-green comet named C/2022 E3 (ZTF) will make a close approach to Earth for the first time in 50,000 years. Swooping within 26 million miles (42 million kilometers) of our planet, the comet will offer a rare night-sky spectacle last seen when modern humans shared our planet with Neanderthals.

But you don't have to wait until February for your chance to glimpse the comet; it is already visible in the late night and early morning sky. Stargazers have been following the comet's path for weeks now and got a particularly good look at it on Jan. 12, when the comet made its closest approach to the sun (a phenomenon called perihelion).

As of Jan. 30, skywatchers are reporting that the comet has a brightness value of magnitude +4.6, meaning it is slightly brighter than the faintest objects visible to the naked eye. The comet's brightness may increse further as it swoops nearer to Earth.

Here's everything you need to know about the green comet's path, its trajectory and where to see it over the coming weeks.

The green comet's path

When astronomers first detected C/2022 E3 in March 2022, the comet was racing through the solar system around 399 million miles (642 million km) from the sun, or just within the orbit of Jupiter. Even though the object was faint — about 25,000 times fainter than the dimmest stars visible to the naked eye, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com — the researchers soon made out a distinct tail, or coma, proving the object was indeed a comet rather than an asteroid. (Asteroids are rocky objects, while comets are made of ice and dust particles that gradually vaporize as the comet approaches the sun, creating a visible trail. Both types of objects orbit the sun.)

By Jan. 12, 2023, the comet had zoomed nearly 300 million miles (482 million km) closer to Earth, becoming visible in the night sky near the northern constellation Corona Borealis. While making its closest approach to the sun, a blast of solar particles called a coronal mass ejection swept over the comet and ripped off part of its tail, dazzling stargazers.

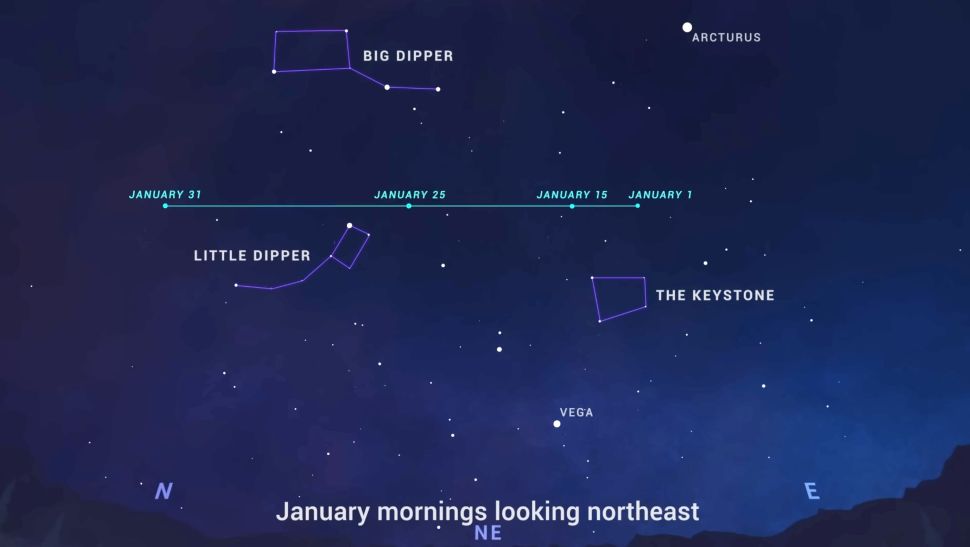

From there, the comet has continued moving westward across the sky. On the nights of Jan. 26 and 27, the comet was visible just east of the Little Dipper's bowl. By Feb. 1, when the comet makes its closest approach to Earth, it will appear near the constellation Camelopardalis, not far from the Big Dipper.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A few days later, on Feb. 5 and 6, the comet will pass across the night sky to the west of the star Capella and then seem to enter the constellation Auriga. From there, it will descend toward Taurus, becoming ever dimmer as it moves away from Earth, back out toward the edge of the solar system.

The green comet's trajectory

Prior to the comet's recent jaunt near our sun, C/2022 E3's orbit took it far beyond our solar system for roughly 50,000 years. Astronomers aren't sure exactly how far the comet will travel after leaving Earth behind this time, but the consensus seems to be that C/2022 E3 is on course to leave our solar system entirely.

After that, humans may never see it again: The latest calculations suggest that the comet is moving on a parabolic orbit, meaning it is not bound to our solar system and is unlikely to come near it ever again, according to Space.com. It's possible that the gravity of some unknown deep-space object could alter the comet's orbit slightly, putting it back on a course that runs through our solar system. But if this happens, it will still likely be millions of years before C/2022 E3 has another close encounter with Earth.

So enjoy the comet now, while you can.

Viewing the green comet

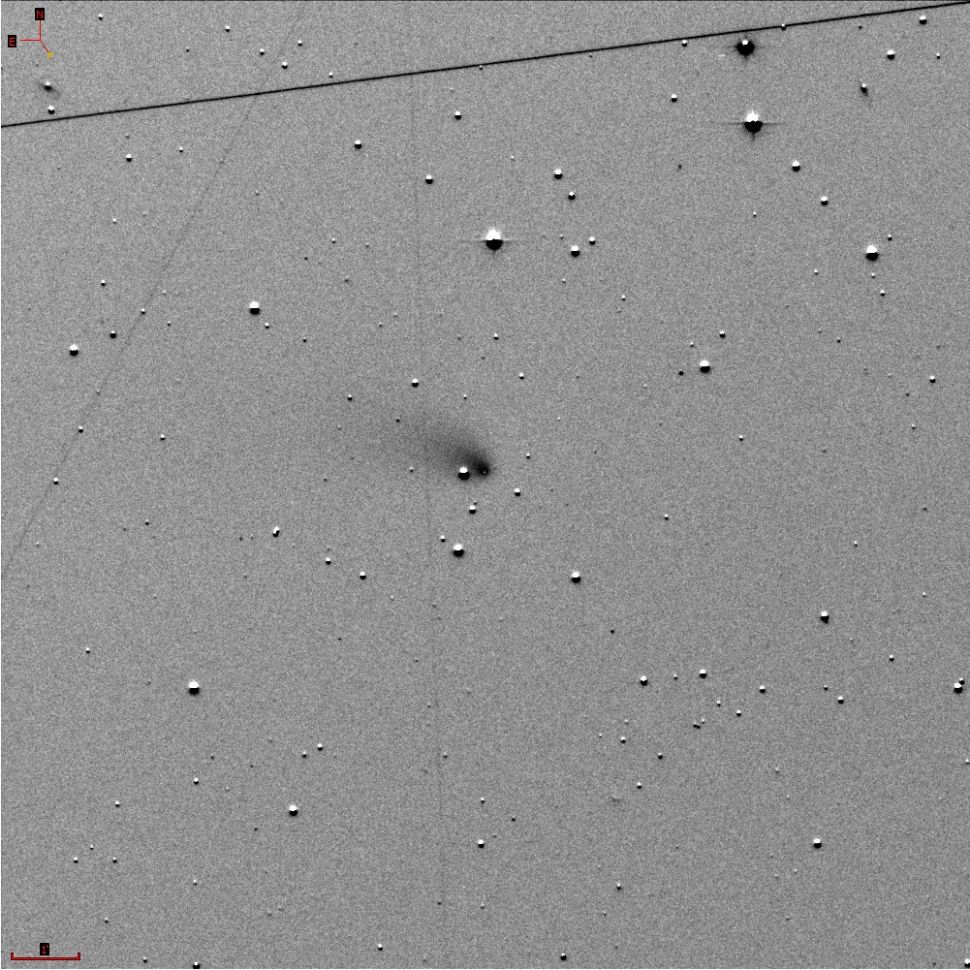

When the comet swoops past Earth on Feb. 1, it will be about as bright as the dimmest stars in the night sky. However, the comet will not look like a sharp, pointed star but rather a diffuse, glowing blur that may spread its light over an area as large as the full moon.

Stargazers living in cities or other light-polluted areas will have a hard time viewing the comet. Joe Rao, a skywatching columnist for Space.com and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium, advises would-be comet watchers to head to the darkest spot possible, allow your eyes to adjust to the dark for 20 to 30 minutes, then look toward the North Star, Polaris, which is located at the end of the Little Dipper's handle.

Using just your unaided eyes, look for the comet's glowing aura around this region of the sky. It may be easier to spot the comet this way rather than by trying to pinpoint it with binoculars or a telescope, according to Space.com. However, once you've spotted the comet, switching to a telescope or binoculars is recommended for the best view.

Viewers using telescopes can find the green comet's up-to-date coordinates on the skywatching website The Sky Live.

Viewers in light-polluted area who may miss the comet can watch a live stream of its close approach on Feb. 1 courtesy of the Virtual Telescope Project.

Why is C/2022 E3 green?

The comet itself isn't green, but its head does appear to glow green thanks to a somewhat rare chemical reaction. The glow likely comes from diatomic carbon (C2) — a simple molecule made of two carbon atoms bonded together. When ultraviolet light from the sun breaks this molecule down, it emits a greenish glow that can last for several days, according to a 2021 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This eerie light disappears before making its way to the comet's tail, or coma, which is made of gas. That gas is once again a result of solar radiation — in this case, sunlight causes part of the comet to sublimate, or transition from a solid into a gas without entering a liquid state. That gas streaks behind the comet, often glowing blue from the ultraviolet light.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus