Flu season is getting weirder

A second strain of flu is hitting the U.S mid-season.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Coronavirus may be in the headlines, but it's still flu season, and a weird one at that — officials are seeing a new spike in flu activity as a second strain of flu hits on the heels of the first.

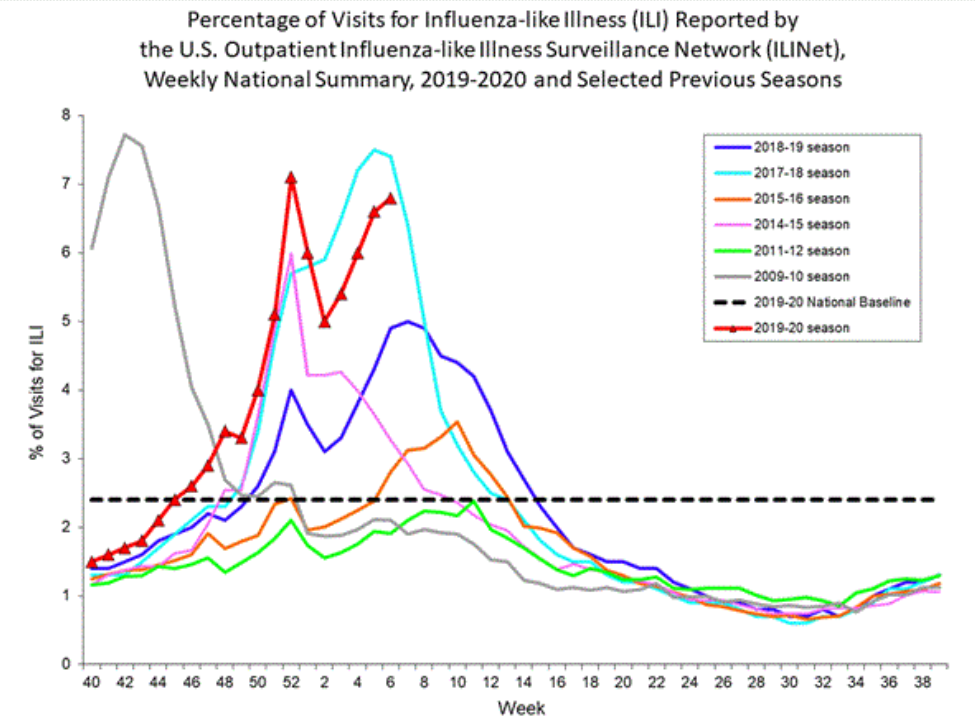

The 2019-2020 flu season already had an unusual start — in December and early January, the main strain of flu virus circulating was a type called influenza B, Live Science previously reported. Typically, influenza B does not cause as many cases as influenza A strains (H1N1 and H3N2) and tends to show up later in the flu season, not at the beginning. Indeed, the last time influenza B dominated flu activity in the U.S. was during the 1992-1993 flu season, according to the CDC.

But now, influenza A is making a comeback. In recent weeks, there has been a surge in activity of H1N1 in the U.S., according to data from the CDC. And that means even more people are going to the doctor for flu — the percentage of people visiting the doctor for flu-like illness increased from 6.6% of all visits last week to 6.8% of all visits this week, according to the CDC.

This type of "double-barreled" flu season is unusual, according to Healthline. Although something similar did happen last year, in which an initial wave of H1N1 activity was followed by a wave of H3N2 activity.

"We may well have, for the second year in a row — unprecedented — a double-barreled influenza season," Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, told WebMD.

So far this season, there have been an estimated 26 million illnesses, 250,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths from flu, according to the CDC.

Although the number of hospitalizations are typical for this time of year, officials are seeing higher-than-typical hospitalization rates among children, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in a news conference today (Feb. 14).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As officials talk about the potential threat of coronavirus in the U.S., "I want to remind everyone of the very real threat of seasonal influenza," Messonnier said.

And with H1N1 activity increasing, it could mean flu season will drag out longer than usual, according to Healthline.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus