Fish defy death to rub up against great white sharks. Here's why.

Fish keep their friends close and their enemies closer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Fish keep their friends close and their enemies closer ... but only because they need to exfoliate.

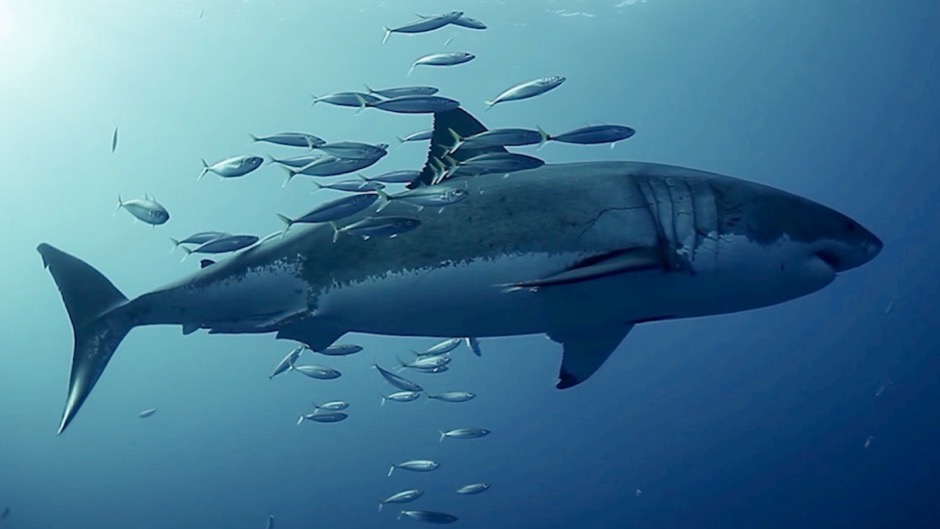

Researchers recently discovered that different species of fish use sharks as scrub brushes by pushing up against the sea predator's scaly bodies to get rid of parasites and other irritants. Though this dangerous behavior has been observed before, it wasn't clear just how common it was.

"While chafing has been well documented between fish and inanimate objects, such as sand or rocky substrate, this [shark-chafing] phenomenon appears to be the only scenario in nature where prey actively seek out and rub up against a predator," Lacey Williams, a graduate student at the University of Miami, who co-led the study with graduate student Alexandra Anstett, said in a statement.

Related: Photos of the largest fish on Earth

Williams and Anstett first observed this behavior with drones, while collecting data on great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in Plettenberg Bay, South Africa, Williams said in a YouTube video about the findings. But it wasn't until they saw this same chafing behavior in a social media post from the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, that they realized that their observations weren't an isolated incident.

To figure out just how common this behavior was, the researchers compiled data from photos, videos, drone footage and witness reports and discovered 47 total instances of fish rubbing against sharks in 13 different locations across the world, according to the statement. They observed this phenomenon across 12 different fish species and eight shark species.

For example, leervis fish (Lichia amia) scrub themselves using the rough skin of great white sharks,silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis) and whale sharks (Rhincodon typus), according to the statement. The number of exfoliating fish varied from one to over 100 individuals at a time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's not clear why fish use sharks as exfoliators, but the researchers ventured a guess.

"Shark skin is covered in small tooth-like scales called dermal denticles, which provide a rough sandpaper surface for the chafing fish," senior author Neil Hammerschlag, an associate professor at the University of Miami, said in the statement. "We suspect that chafing against shark skin might play a vital role in the removal of parasites or other skin irritants, thus improving fish health and fitness."

It's also unknown why there are no known instances of a land animal rubbing against another to chafe. "We hope this paper sparks ideas for future studies so that we can better understand our marine and freshwater systems," she said.

The study appeared Oct. 28 in the journal Ecology, The Scientific Naturalist.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus