Handwritten Einstein letter containing famous E=mc2 equation sells for $1.2 million

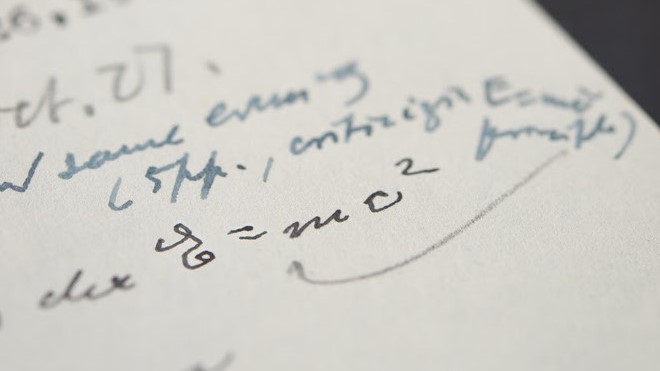

It is one of only four known examples of the famous equation written by the physicist in his own hand.

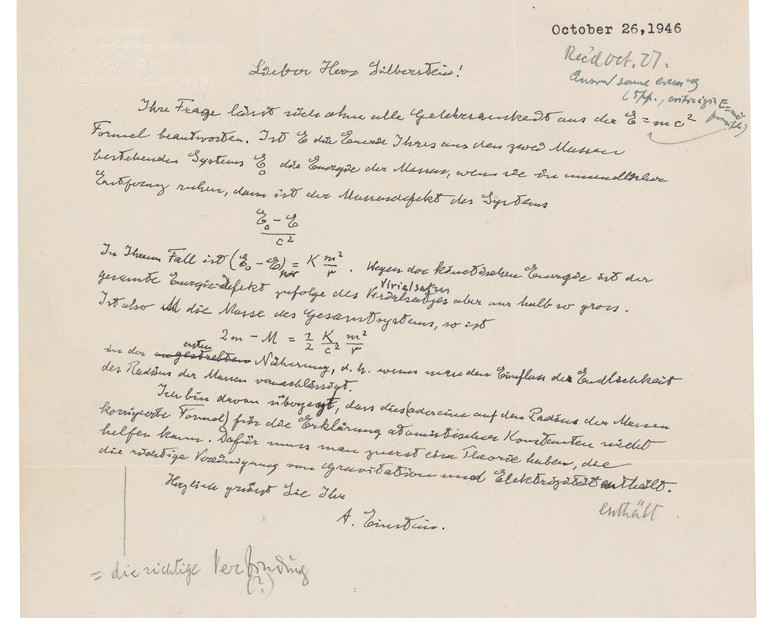

A “lost” letter written by Albert Einstein to a rival physicist recently sold to an anonymous collector for $1.2 million at auction. The handwritten letter includes Einstein's famous E=mc2 equation and is one of just four known examples of the equation in the physicist’s own handwriting, according to archivists from the Einstein Papers Project at Caltech and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

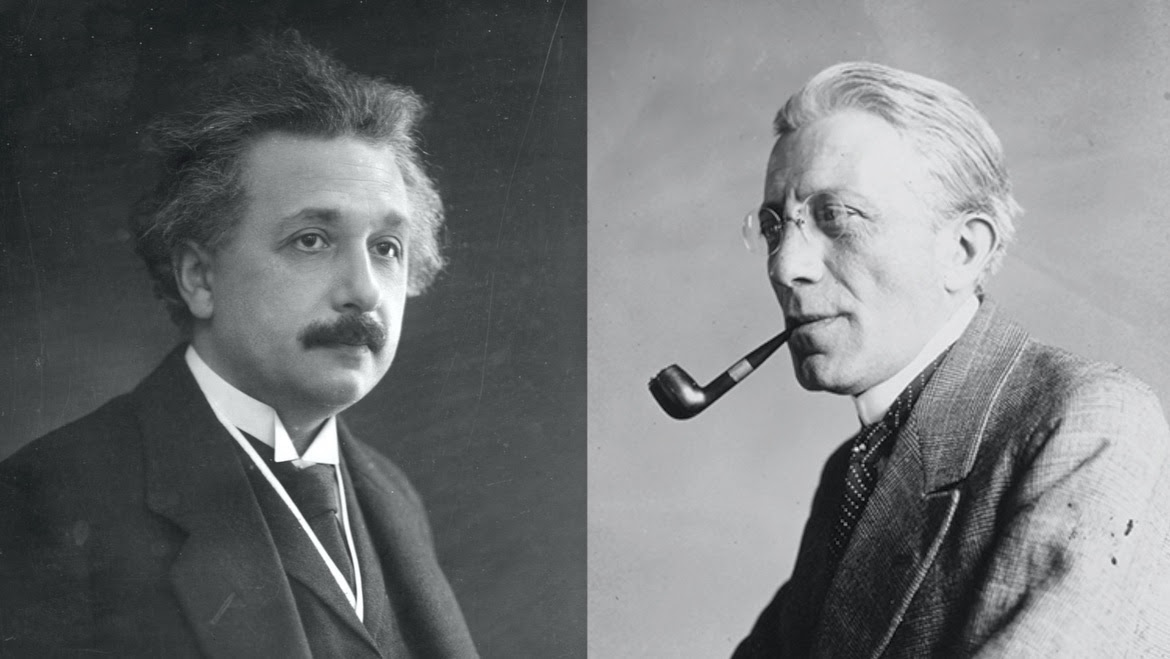

The one-page letter, written in German on paper with Einstein's blind-stamped personal Princeton letterhead, was sent to Polish American physicist Ludwik Silberstein, a well-known critic of some of Einstein's theories at the time. The document is signed "A. Einstein" and is dated Oct. 26, 1946.

The letter remained in Silberstein's archives and was recently auctioned off by his family. The document was expected to sell for $400,000, but ended up going for three times that after a late bidding war between two parties on May 18, according to RR Auction, the Boston-based company that sold the letter.

Related: 8 ways you can see Einstein's theory of relativity in real life

"E = mc2 is the most famous equation in the world," Bobby Livingston, executive vice president at RR Auction, said in a statement. For that reason, it is "an important letter from a physics point of view."

Einstein first published the equation — energy equals mass times the speed of light squared — in a scientific paper in 1905. The idea behind the equation is that energy and mass are essentially just different forms of the same thing and can switch from one to the other, although the conditions required to do so are extreme, according to NOVA.

Prior to the publishing of the E=mc2 equation, physicists treated mass and energy as two separate entities that were only loosely related to each other. But in just a few strokes of his pen, Einstein changed this forever by proving they were actually two sides of the same coin, according to Discover Magazine.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The equation also allowed Einstein to prove his theory of special relativity — which states that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light in a vacuum because an object traveling at that speed would have infinite mass and therefore require infinite energy to move. Special relativity also changed physics by introducing the concept of space-time, which laid the groundwork for Einstein's later theory of general relativity, published in 1915, which showed that gravity is the result of distortions in space-time caused by objects moving through it.

In the letter, Einstein writes the famous equation to highlight the energy difference between two masses at both an infinite distance and a specified distance from each other, in response to a query from Silberstein. "Your question can be answered from the E = mc2 formula, without any erudition," Einstein wrote in the letter, translated from German.

Collectors were also drawn to the letter because it mentions the need for a unified field theory — a single theory that ties together all the fundamental forces of nature — currently considered to be the holy grail of modern physics.

Researchers recently reported on the discovery of another letter written by Einstein, this one suggesting that there could be a link between the migrations of birds and "unknown" physical processes, Live Science previously reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus