Prohibition-era gangster may have buried $150 million in treasure

His death sparked rumors of a buried box filled with diamonds, gold coins and thousand-dollar bills.

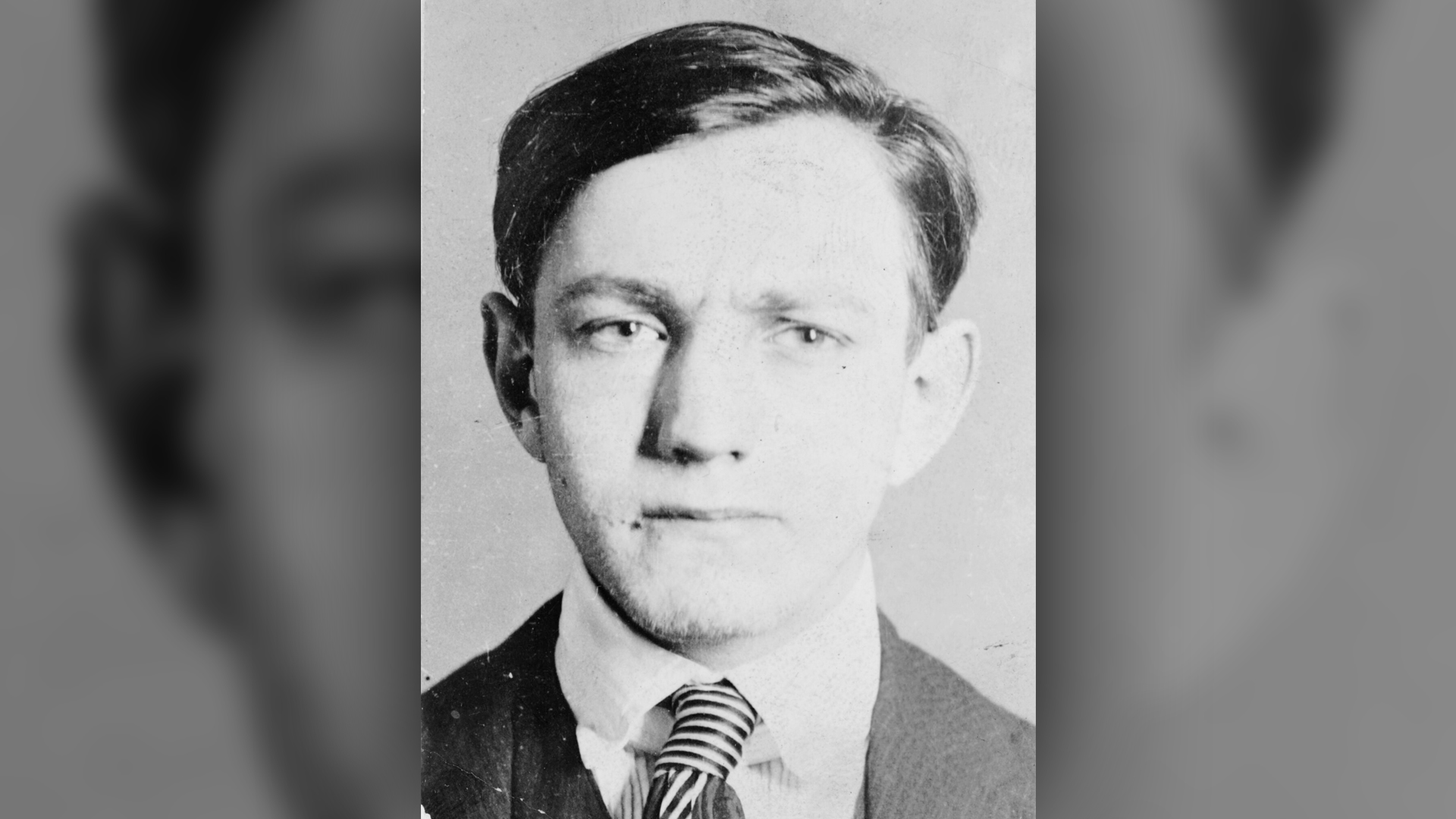

When the notorious bootlegger and gangster Dutch Schultz was gunned down in 1935, rumors flew about the fortune that he supposedly left behind. Legend had it Schultz had hidden valuables now worth more than $50 million (and possibly as much as $150 million), including gold coins, thousand-dollar bills, diamonds and uncashed World War I Liberty Bonds, all stuffed into a strongbox and buried somewhere in the wilds of upstate New York.

But the existence of this treasure was never proven, and its location — if it ever existed — is a long-standing mystery.

Almost a century later, Schultz's mythical cache of riches has yet to be discovered. But determined treasure seekers are certain that it's out there — and they're still looking. In the PBS show "Secrets of the Dead: Gangster's Gold," which premiered Nov. 18, three teams set out to solve the 85-year-old puzzle, tracking down long-hidden tunnels and hideouts and hoping that satellite maps and ground-penetrating radar will lead them to the buried loot.

Related: 30 of the world's most valuable treasures that are still missing

Born Arthur Flegenheimer to German-Jewish parents in 1902, Schultz began a career of lawbreaking when he was still a boy in the Bronx. He eventually earned a reputation as an exceptionally vicious criminal mastermind, using extreme violence to enforce illicit operations such as bootlegging, extortion and illegal lotteries that extended throughout New York and New Jersey, according to PBS.

When Prohibition went into effect in 1920, Schultz quickly recognized it as a moneymaking opportunity. He seized control of the Bronx's illegal beer supply, running it with an iron fist, said Nate Hendley, a journalist and author of "Dutch Schultz: The Brazen Beer Baron of the Bronx" (Fiver Rivers Publishing, 2011). Schultz's plan was simple: threaten and intimidate every speakeasy owner in the borough into buying only from him — or they would suffer the consequences.

One gruesome story described Schultz and his partner kidnapping a saloonkeeper who was reluctant to do business with them. They hung the man by his thumbs, tortured him, then covered his face with fabric that had been dipped in gonorrhea sores, Hendley told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"After he was ransomed and released, he went blind from the infection," Hendley said. "That sent a strong message to saloonkeepers to buy from Dutch."

Schultz later branched out into restaurant racketeering — extorting protection money from restaurant owners and workers — and muscled in on the numbers racket, or illegal lotteries, in Harlem. At one point he was raking in approximately $12 million to $14 million per year from the lotteries alone, Hendley said.

"Factor in inflation and it's worth over 10 times that today," Hendley said. "He was making a lot of money, even by illicit gangster standards. By all estimates, he was one of the wealthiest gangsters in New York at the time."

"My collection of papers"

Most of Schultz's crime empire was centered around New York City. However, he also spent a lot of time in upstate New York, minding his breweries and visiting rural communities to distribute bribes and cultivate goodwill when he was on trial for tax evasion, according to Hendley.

After Schultz tried to kill a federal prosecutor — disregarding other powerful mobsters' warnings to back off — gangster rivals arranged for Schultz's murder, and a hit man shot him in a restaurant in Newark, New Jersey, on Oct. 23, 1935. Rumors of Schultz's missing treasure began circulating almost immediately after his death, because neither Schultz's common-law wife nor anyone in his family stepped forward to claim ownership of the vast fortune he must have amassed from his criminal activities.

Schultz would likely have avoided banks and stashed his ill-gotten loot in places where it couldn't be traced or taxed, and Schultz's lawyer Dixie Davis claimed to have seen "a big lockbox full of money, bonds and coins," adding that Schultz spoke about burying the loot so that the government would never get it, Hendley said. But Davis' claims about the lockbox were never verified.

"It's a mystery as to where his money went," Hendley said.

Still more rumors about the allegedly buried treasure arose from Schultz's deathbed ravings, delivered to Newark police while he was manacled to a hospital bed, delirious with a fever of 106 degrees Fahrenheit (41 degrees Celsius) and dosed with morphine. A stenographer carefully recorded Schultz's "statements" from the gangster's bedside in the hours before his death; Schultz mentioned "my collection of papers" and said that he had been shot "over a million, five million dollars," according to a transcript published on Oct. 26, 1935, by The New York Times.

But Schultz also muttered streams of utter nonsense, including, "Get you onions up, and we will throw up the truce flag" and "No payrolls. No walls. No coupons." As he grew weaker, his rantings became less and less lucid. Before Schultz lost consciousness for the last time, he called out, "French-Canadian bean soup," the Times reported.

"You could take bits and pieces of it and say he might be giving out clues, but he was dying," Hendley said. "I can't make any sense of it at all — but who knows?"

"Secrets of the Dead: Gangster's Gold" premieres Nov. 18 at 10 p.m. on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/secrets and the PBS Video app.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.