Cold War satellites tracked missiles ... and marmots?

The historic images could fill gaps in the ecological record.

The U.S. launched espionage satellites during the Cold War to locate Soviet missile sites, but in doing so, they also captured photos of animals and their historic habitats, Science magazine reported.

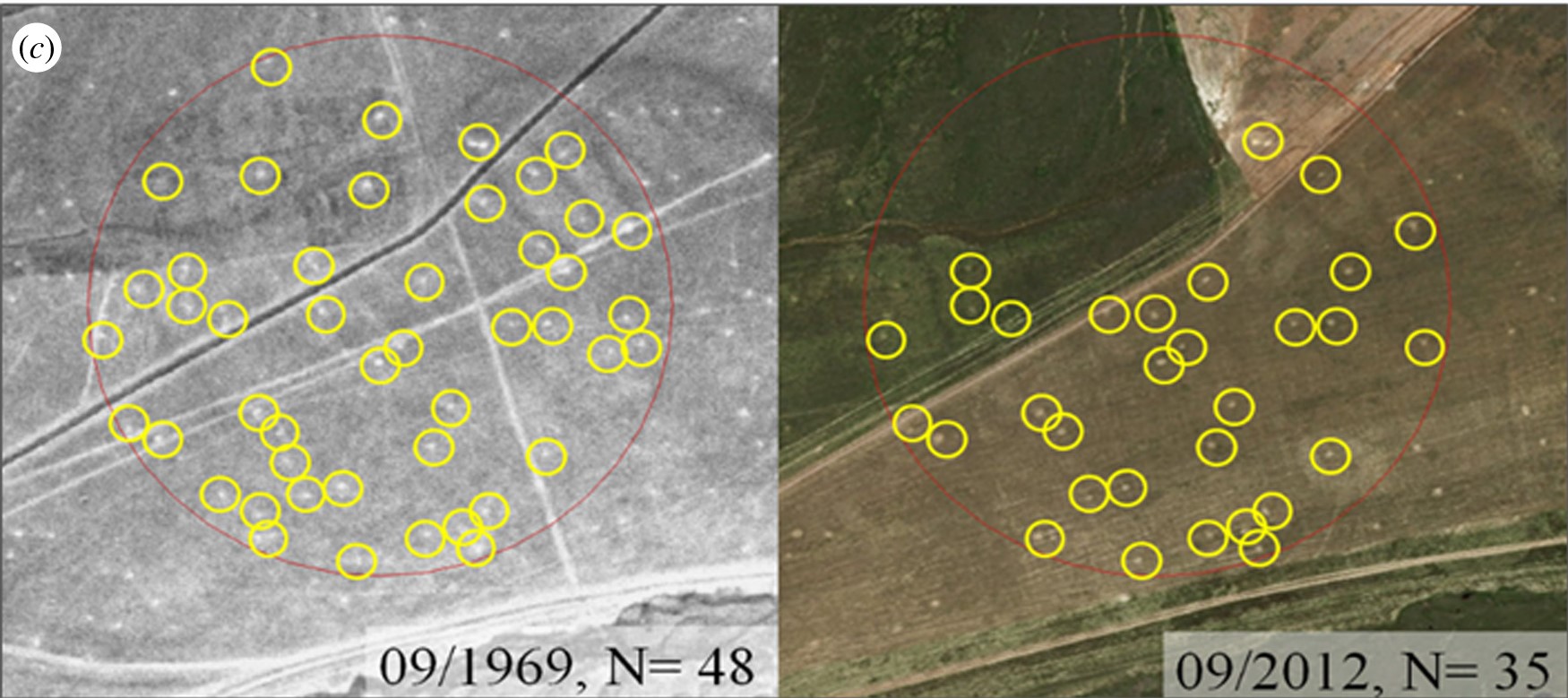

Now, scientists have put these 1960s snapshots to new use: showing how a specific population of marmots in Kazakhstan has dwindled over the last five decades.

The same approach could be used to study how other animal populations have changed through time, particularly in regions with little historic data on record, the authors wrote in a report published May 19 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Related: The 12 weirdest animal discoveries

Using a U.S. Geological Survey database, the team collected black-and-white images captured by Cold War-era satellites launched as part of a U.S. espionage program called Corona. Poring over images of the grasslands of northern Kazakhstan, they searched for evidence of bobak marmots (Marmota bobak) — large prairie dog-like rodents that live in underground burrows, which they can use for many decades. The team identified more than 5,000 marmot burrows in the historic photos and estimated that, since the 1960s, about eight generations of marmots have occupied some of those very same burrows.

However, far fewer bobak marmot burrows exist today than did 50 years ago. The number of burrows declined by about 14% across the entire region, and by as much as 60% in grasslands that had been converted into wheat fields, the study found.

Related: Beasts in battle: 15 amazing animal recruits in war

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Marmots often return to rebuild burrows disrupted by farming, but in heavily cultivated areas, the energetic cost of reconstructing burrows over and over again may prove too great, the authors wrote. This may explain why marmot populations fell steeply in the oldest wheat fields included in the study, as those were subject to persistent plowing over many years, they wrote.

The work may be the longest record of how mammals respond to their habitat being developed for agriculture, study author Catalina Munteanu, a geographer at Humboldt University of Berlin, told Science magazine.

Using historic satellite images and other archived data could help humans better manage activities to reduce our impact on animal habitats, Daniel Blumstein, an ecologist and marmot expert at University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study, told Science.

- Wipe out: History's most mysterious extinctions

- Biblical battles: 12 ancient wars lifted from the bible

- Busted: 6 Civil War myths

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus