Monster black hole spotted 'giving birth' to stars

The Hubble telescope just spotted a 500-light-year-long 'umbilical cord' for baby stars

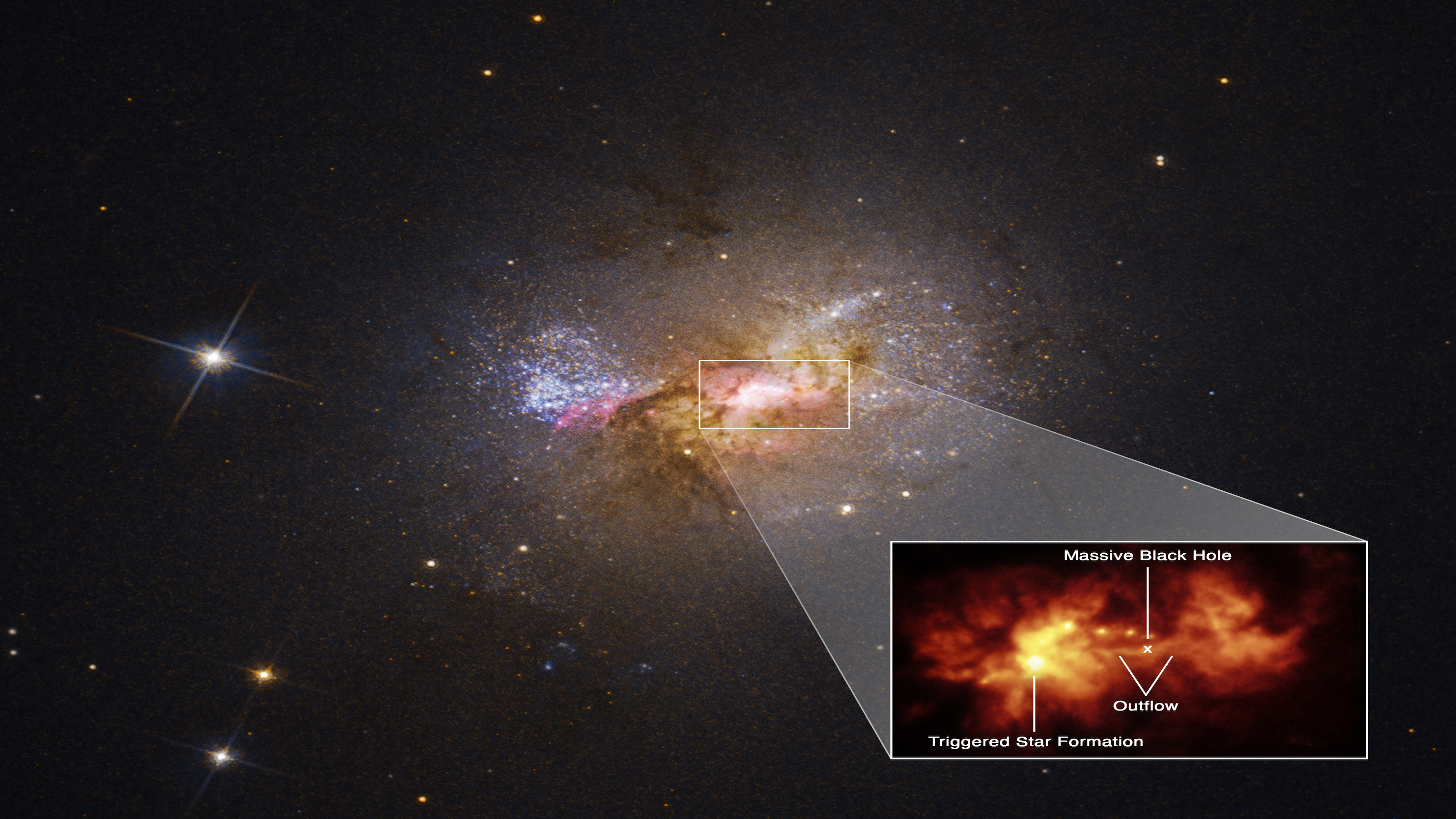

Astronomers have spotted a black hole "giving birth" to stars at the center of a nearby dwarf galaxy — and the stellar newborns are tethered to the black hole by a massive "umbilical cord" made of gas and dust.

The supermassive black hole, situated roughly 34 million light-years away in the galaxy Henize 2-10, was seen spewing an enormous, 500-light-year-long jet of ionized gas from its center at around 1 million mph (1.6 million km/h), contributing to a "firestorm" of new star formation in a nearby stellar nursery.

The discovery, made using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, is the first time a black hole in a dwarf galaxy (a galaxy with 1 billion or fewer stars) has been seen birthing stars. The remarkable finding was described in a study published Jan. 19 in the journal Nature.

Related: The 10 wildest things we learned about black holes in 2021

"From the beginning, I knew something unusual and special was happening in Henize 2-10, and now Hubble has provided a very clear picture of the connection between the black hole and a neighboring star-forming region located 230 light-years from the black hole," study co-author Amy Reines, an astrophysicist at Montana State University, said in a statement. "Hubble's amazing resolution clearly shows a corkscrew-like pattern in the velocities of the gas, which we can fit to the model of a precessing, or wobbling, outflow from a black hole."

Astronomers observed the jet's thin tendril stretching out from the black hole and across space to a bright stellar nursery. Supermassive black holes — which are millions to billions the size of stellar-mass black holes — have been spotted spewing cosmic plumes before, but until now, astronomers thought that these jets hindered, rather than helped, star formation in dwarf galaxies.

"At only 30 million light-years away, Henize 2-10 is close enough that Hubble was able to capture both images and spectroscopic evidence of a black hole outflow very clearly, lead author Zachary Schutte, a graduate student at Montana State University, said in the statement. "The additional surprise was that, rather than suppressing star formation, the outflow was triggering the birth of new stars."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Black holes make the jets that spew from them by sucking in material from nearby gas clouds or stars before slingshotting it back into space in the form of blazing plasma traveling close to the speed of light. If heated to the right temperature, the gas clouds that make contact with the jet will then become ideal nurseries for future stars.

But getting to that Goldilocks zone is crucial; if the jets heat the gas clouds up too much, they can lose their ability to cool back down in the way necessary for star formation, according to NASA. But with the gentle, less-massive outflow from the black hole in Henize 2-10, gas conditions were perfect for star formation.

As this black hole has remained relatively small over time, the researchers believe that studying it in more detail could help them to understand the smaller origins of larger supermassive black holes in the universe, and what processes made them balloon to such enormous scales. Plus, the high-resolution method the team developed to spot the black hole's dim signature can now be used to find others like it.

"The era of the first black holes is not something that we have been able to see, so it really has become the big question: Where did they come from?" Reines said. "Dwarf galaxies may retain some memory of the black hole seeding scenario that has otherwise been lost to time and space."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus