'If it was a man, we would say that's a warrior's grave': Weapon-filled burials are shaking up what we know about women's role in Viking society

New research is finding that some women in Viking Age Scandinavia were buried with war-grade weapons. Experts are divided about what that means.

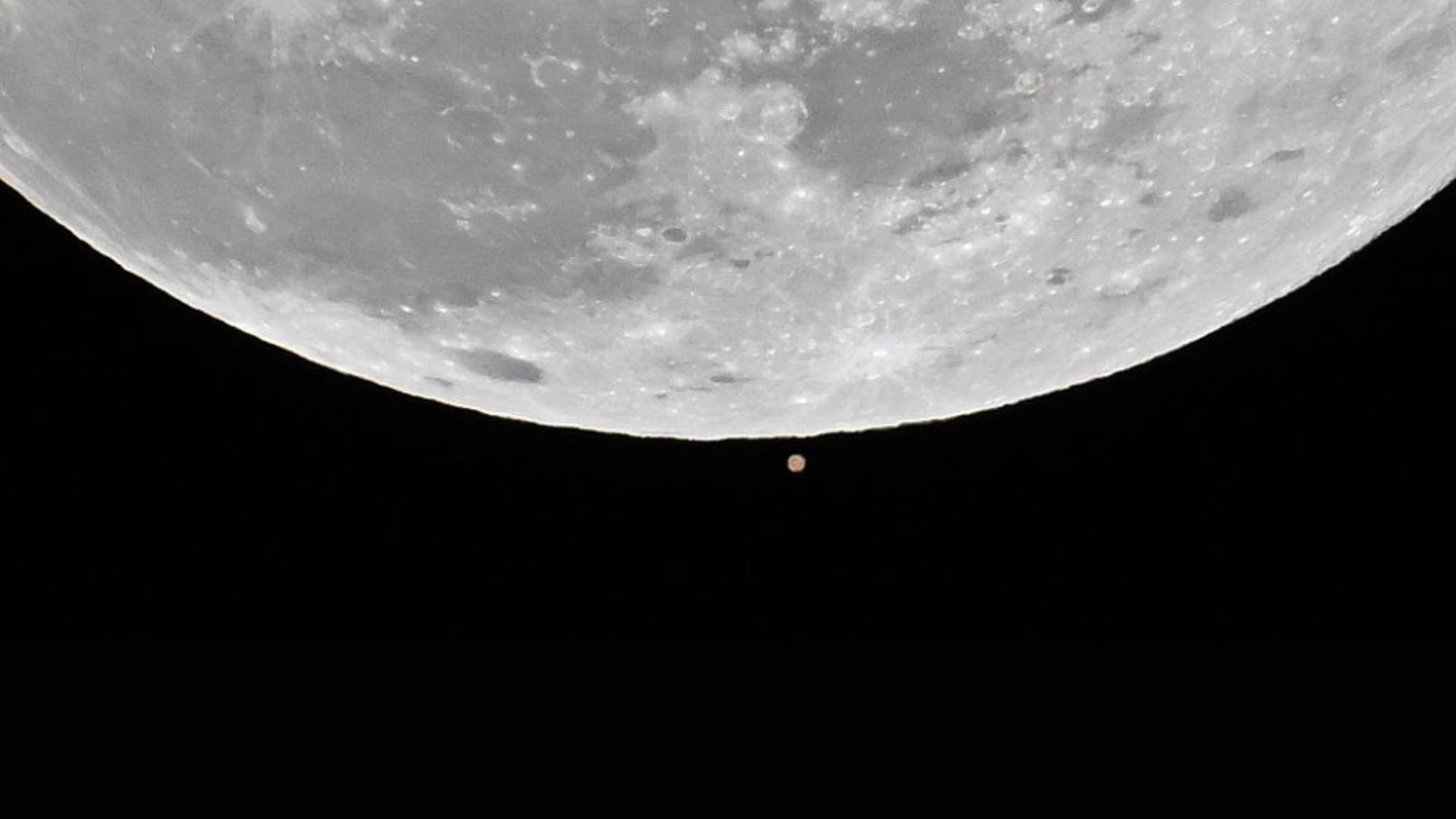

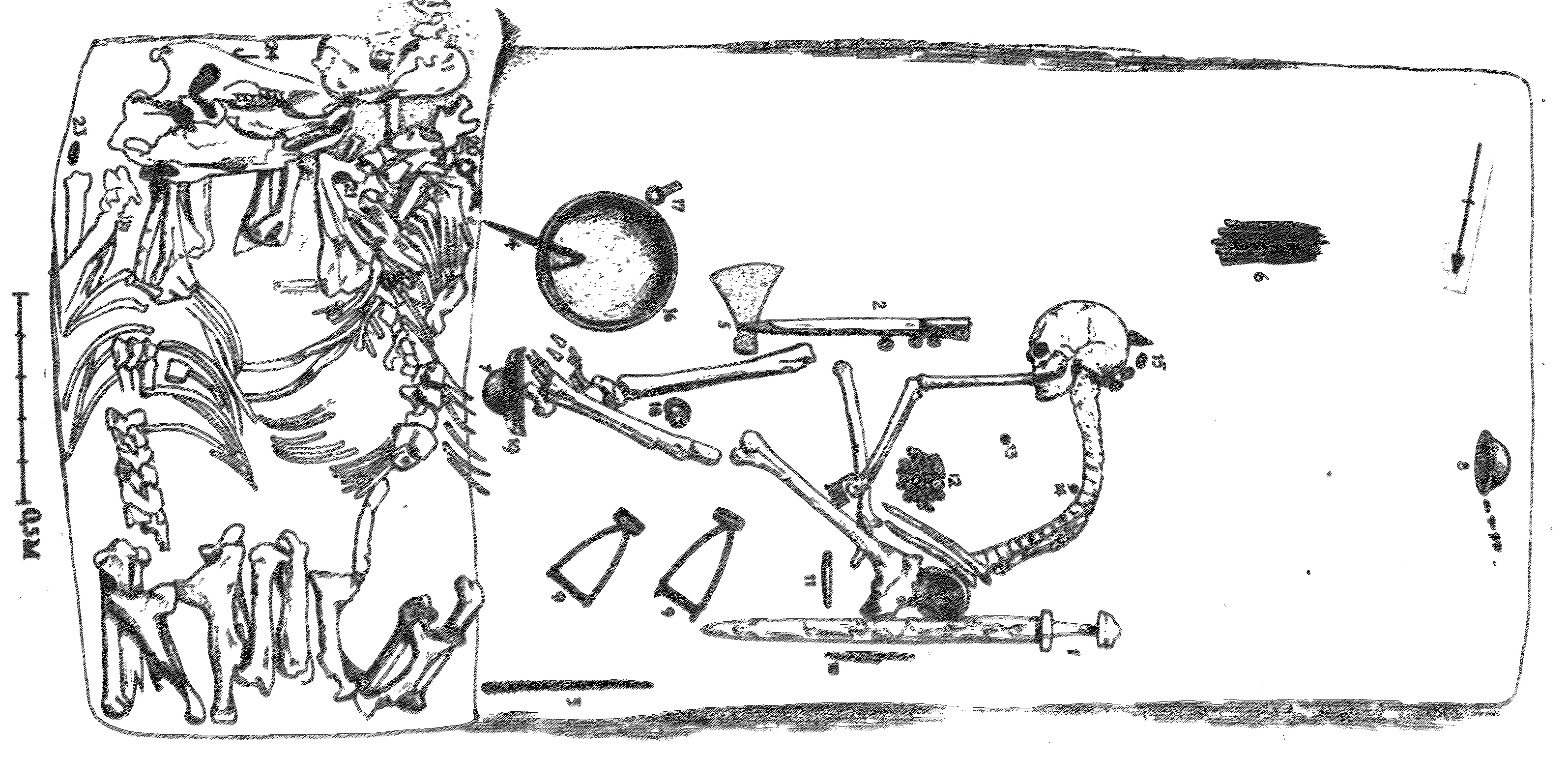

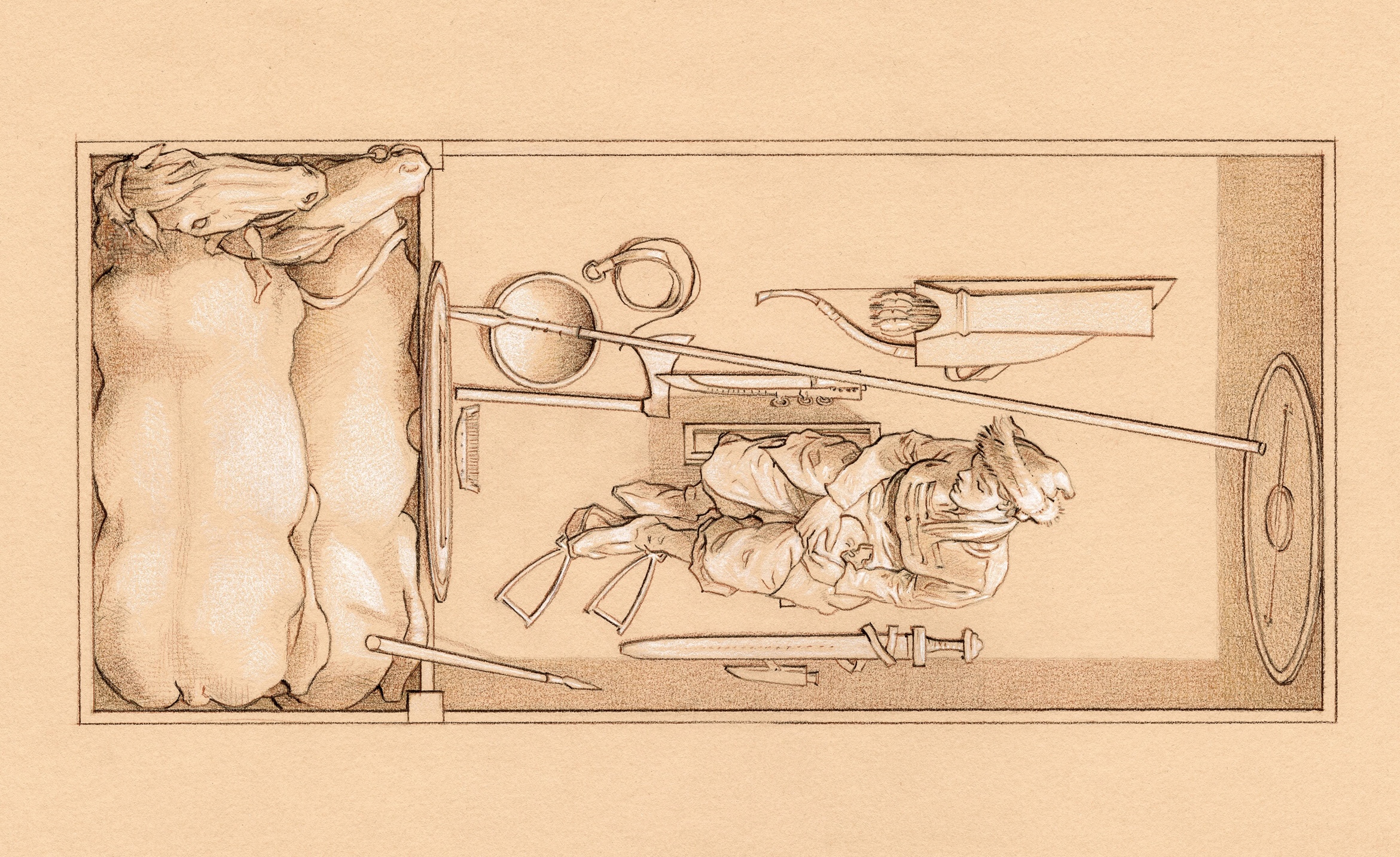

In Birka, Sweden, there is a roughly 1,000-year-old Viking burial teeming with lethal weapons — a sword, an ax-head, spears, knives, shields and a quiver of arrows — as well as riding equipment and the skeletons of two warhorses. Nearly 150 years ago, when the grave was unearthed, archaeologists assumed they were looking at the burial of a male warrior. But a 2017 DNA analysis of the burial's skeletal remains revealed the individual was female.

Skeptics scrambled to explain away the evidence, said Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, an archaeologist at Uppsala University in Sweden and first author of the 2017 study.

Even now, despite further studies strengthening the case for the Birka individual's martial profession, some archaeologists still insist she wasn't a warrior.

The Birka controversy highlights the fraught archaeological debate about the existence of Viking women warriors. Viking mythology and lore are filled with tales of women who lived for battle and engaged in violence, but whether these stories reflect real life is unsettled.

Across Scandinavia, at least a few dozen women from the Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066) were buried with war-grade weapons. Collectively, these burials paint a picture that clashes violently with the hypermasculine image of the bearded, burly Viking warrior that has dominated the popular imagination for centuries. And it's possible that, due to gendered assumptions, archaeologists may be systematically undercounting the number of Viking women buried with weapons.

The finds hint at a nuanced picture of Viking society — one where most warriors were men but a person's class and profession had the biggest impact on who went to war.

"Women can be as strong, as skilled, as fast as men," said Leszek Gardeła, an archaeologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and author of "Women and Weapons in the Viking World: Amazons of the North" (Casemate, 2021). "There is nothing in the biology there that would prevent them from being warriors."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, the poor preservation of Scandinavian graves, the enigmatic nature of Viking burials and the lack of historical texts leaves the meaning of many female burials up for debate. And even if women warriors existed, their significance in the broader Viking culture is unclear, Ole Kastholm, a prehistoric archaeologist and senior researcher at Roskilde Museum in Denmark, told Live Science.

"It's an area where we can't find a secure answer," he said.

Related: What's the farthest place the Vikings reached?

What the burials hold

Across Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland, there are thousands of known Viking burials typically thought to be of male warriors. In contrast, we know of around 30 graves in which women were buried with obvious martial equipment such as spearheads and shields; of these roughly 30, only three have swords.

Of the known Viking Age burials, "statistically speaking, there would be less than 1%" of women buried with weapons among graves of men buried with weapons, Gardeła told Live Science.

But there are many more female burials that included other gear, such as shield bosses (a round protective metal piece at the shield's center), or possible weapons, such as arrowheads and ax-heads. Interpreting the latter burials is especially challenging because axes and arrowheads were used in battle, but they were also tools for hunting and farmwork.

But one of the main reasons the female-warrior question is so controversial is that many Viking burials aren't in great condition.

The Birka burial is one example. In 1878, workers used dynamite to blast open the grave, damaging it in the process. Untrained locals then helped excavate the grave. This poor excavation work has given naysayers room to argue that the chamber once held a double burial with a man.

According to the skeptics, "a woman would never be strong enough to use those weapons" — an argument that was ridiculous to Hedenstierna-Jonson, who had actually handled them.

"There were all these opinions rather than scientific facts," Hedenstierna-Jonson told Live Science.

Yet modern-era damage isn't the biggest obstacle to analysis. In many cases, bones and cremated remains are partially or completely decayed before archaeologists get a peek, largely due to Scandinavia's acidic soil. "We need very good preservation of the skeletons before we can determine the sex" via DNA analysis or bone studies, Kastholm said. "So even though the Viking Age has been investigated for like 150 years or more, it has not been that easy" to assess these graves.

"Occam's razor, you know — the simplest explanation is usually the best. If you find a woman with a sword, then you should interpret it the same as you would a man with a sword."

Marianne Moen, head of the Department of Archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo

As a result, archaeologists often guessed the deceased's sex based on grave goods, such as mirrors, weaving tools and brooches, which archaeologists assumed were typically buried with females, and battle-related weapons, which archaeologists thought were typically buried with males. If a Viking Age sword was the only item recovered, for example, it was nearly always assumed to be a male grave.

So it's possible archaeologists may be systematically undercounting Viking women who were buried with weapons.

"We could have a lot more of these [female] graves than we know about," said Marianne Moen, head of the Department of Archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo, calling the situation a catch-22. "You excavate a grave in Norway, you find a sword and you go, 'Oh, it's a man.' And then, 'isn't it funny how all the swords are buried with men?'"

In some instances, if a burial had both male- and female-associated artifacts, it is assumed, possibly incorrectly, that it was a double burial with a male and a female.

Even with that potential bias, there is strong evidence that some women were buried with war-related objects across Scandinavia. Norway has several of what have been nicknamed "shield-maiden" burials, after the women warriors of Scandinavian folklore. One is the Nordre Kjølen burial in Solør, which had a young adult — likely a female, based on a skeletal analysis — interred with a sword, an ax head, a spearhead, arrowheads, a shield boss, a horse skeleton and tools.

A second is the female boat burial from Aunvoll in Nord Trøndelag, in which a female was interred with a sword, eight gaming pieces, a sickle, a spearhead, shears, a knife and tools. The Klinta burial in Öland, Sweden has the cremated remains of what are thought to be an elite woman with valuable metal artifacts, including an ax-head, knives and an iron staff, causing some to wonder if she was a völva, or a Viking Age sorceress.

And although they're not buried with sharp weapons, "there's quite a few female burials on the west coast of Norway that have shield bosses and nobody likes to talk about them," Moen told Live Science.

Difficult to interpret

Still, many archaeologists struggle to make sense of these graves because the Vikings didn't have a consistent way of dealing with the dead.

"When we look at the Viking Age burials as a whole, they are weird and there's a great variation," Kastholm said. For instance, one had only a foot in it. Another was a triple burial of "a woman, then another woman buried some years later and then a half man buried later."

These mysterious, inconsistent burials make it hard to make straightforward conclusions.

Take the example of a grave discovered in Gerdrup, Denmark, in 1981, Kastholm said. A woman was buried with a spear, with large stones on her body. Her adult son, who had bound ankles and may have been hanged, was also in the grave.

The spear could be a sign the woman was a warrior. But that's not how Kastholm interprets the grave. Instead, he thinks that the son was hanged in devotion to Odin, the stones represent the woman's high status, and the valuable "spear was thrust into the bottom of the grave in a concluding ritual that dedicated the dead to Odin," he co-wrote in a 2021 study. This would have been a form of complex "mortuary theater," a play of sorts that would have been enacted at the grave site, which research suggests may have been common.

As for the Birka burial, Kastholm doesn't dispute that the deceased was biologically female and that she was buried with many weapons. "I'm totally convinced by that," he said. "If that means she was a warrior, I'm not convinced there. But that would go for male graves as well."

What historical texts tell us

To put the burials of women with weapons into context, archaeologists have looked at historical texts.

The Vikings left behind only a few thousand runic inscriptions. So most descriptions of warlike women and "shield maidens" come from semihistorical works written during the post-Viking medieval period. For instance, in "Gesta Danorum," a semifictional history of Denmark by Saxo Grammaticus (who lived circa 1150 to 1220), the warrior woman Lagertha travels with a group of women dressed as men, marries a Viking king who later divorces her, and still fights with him in a pivotal battle.

And some sagas, such as The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek, describe Norse women taking up arms to help protect family property, according to a 1986 analysis. Only men could inherit property, so if a man had only daughters, one was sometimes compelled to step into the role of a warrior as a "functional son" who could protect the family's interests, according to the study.

The Icelandic sagas, written by people who were likely the Viking's descendants in the 13th and 14th centuries, include stories about "women leading troops and engaging in acts of violence," Moen wrote in a 2021 article.

But are these stories evidence that Viking women were warriors in real life? Or did some stories have other mythical or mystical significance?

Some evidence points toward the latter. Sagas in which women wield weapons like axes often have magical overtones. In the Old Norse Ljósvetninga saga, for instance, a cross-dressing Norse sorceress strikes the water with an ax to see into the future. Axes are frequently associated with magic in folk traditions from Scandinavia, Finland and Central Europe, Gardeła noted in a 2021 article.

Gender wasn't destiny

After the Viking Age, the stereotype of the burly and ruthless male Viking warrior arose in the medieval sagas that detailed their exploits, and again in the late 19th century during Scandinavia and Iceland's National Romantic period. But it's possible that Viking Age society was "less governed by binary gendered ideals and more by fluid social obligations," Moen wrote in the 2021 article.

This would mean there wasn't a simple male-female dichotomy in who did what. This is seen in Viking Age grave goods. For instance, at Viking Age cemeteries in Vestfold, Norway, Moen found that although weapons were more common in male graves, they were also found in female burials. Likewise, while jewelry was more pronounced in female graves, 40% of male graves also had them, "hardly a negligible proportion," she wrote in the article.

Given how much violence permeated Viking society, "it would be naïve to think that only one half of the population was invested in it," she wrote in the article.

But people should not see this as female warriors filling a "man's role," Kastholm said. Rather, "warrior" was probably a profession, like modern-day firefighting, in which most were male but some were female.

Even among Viking Age men, being a "warrior" meant different things. Farmworkers, fishers and other peasants may have fought occasionally. But for the most part, the warriors were the social elite.

"Your biological sex was a factor [in your profession], but it was not the main factor," Hedenstierna-Jonson said. "The main factor was your role and your position and your family."

Still, people should be cautious in using information about these burials to infer how gender was perceived in Viking society, Moen said.

"I don't think it even necessarily indicates any kind of gender equality," she said. "What I do think is that you have much evidence women could be warriors and were warriors at certain times and in certain conditions."

"Occam's razor"

Moen splits archaeologists into three groups: those who think the burials clearly show that female warriors existed; people who say, "Yes, obviously women could be buried with weapons, but we need to question what it means"; and naysayers who think there's no way women actually used the weapons they were buried with. "They find it really quite troubling, and they go to very long lengths of explaining it away," she said.

To Moen, the evidence of female Viking warriors is right in front of us.

"Occam's razor, you know — the simplest explanation is usually the best," she said. "If you find a woman with a sword, then you should interpret it the same as you would a man with a sword."

In the end, Kastholm thinks "there will always be a lot of debate. And that debate is more about our time" and our modern-day attachment to gendered stereotypes about the Vikings than it is about the archaeological evidence, he said.

"Of course there were warriors in the Viking Age, and I'm pretty sure that some of them were female," Kastholm said. Yes, many graves are tricky to pin down, but at least a few have an impressive number of hard-core weapons buried with them.

"If it was a man," he said, "we would say 'that's a warrior grave."

Editor's Note: In this article, we are referring to biological sex, as it's impossible to know the gender of these deceased individuals.

Viking quiz: How much do you know about these seaborne raiders, traders and explorers?

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus