Ancient 'urine flasks' for smelling (and tasting) pee uncovered in trash dump at Caesar's forum in Rome

Archaeologists have unearthed 500-year-old 'urine flasks' at a medical dump within Caesar's forum in Rome.

A Renaissance-era trash dump discovered inside the Forum of Caesar in Rome is brimming with old medical supplies, including 500-year-old medicine bottles and urine flasks — containers used to collect patients' pee for medical analysis, a new study finds.

Initially excavated in 2021, the 16th-century medical waste dump was found in the area of Caesar's Forum, which was completed in 46 B.C. and dedicated to Julius Caesar. But a millennium and a half later, a guild of bakers used the exact same space to build the Ospedale dei Fornari (Bakers' Hospital). The hospital's workers then created the dump, according to the study, published April 11 of the journal Antiquity.

During their work, archaeologists with the international collaboration Caesar's Forum Excavation Project discovered a Renaissance-era cistern full of ceramic vessels, rosary beads, broken glass jars and personal items like coins and a ceramic camel figurine. Many of the objects, they suggest, were related to routine patient care at the Ospedale dei Fornari, with each person admitted to the hospital given their own "welcome basket" with a jug, drinking glass, bowl and plate as a hygienic measure.

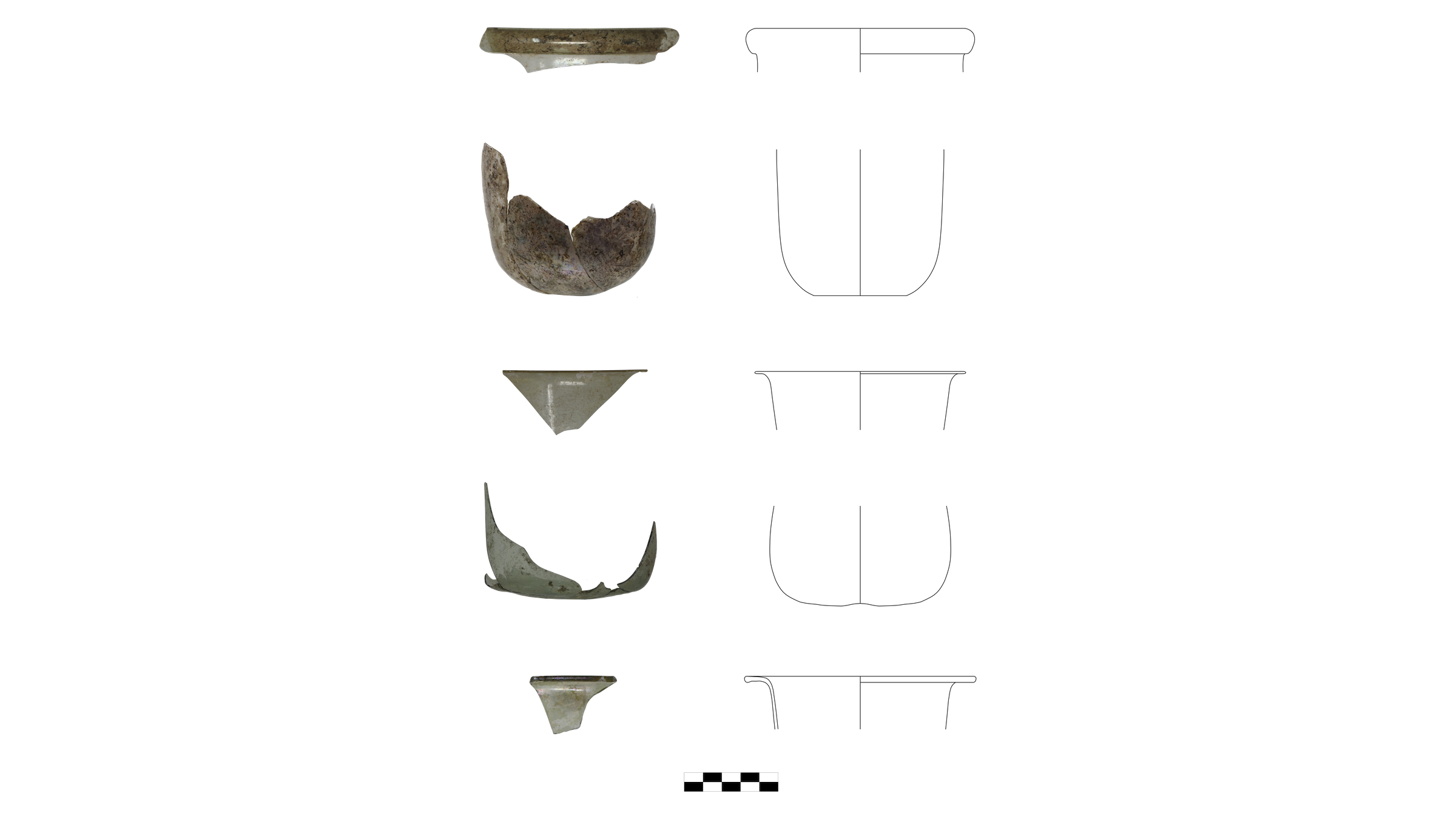

More than half of the glass vessels recovered from the dump are likely what medieval Latin medical texts call matula — urine flasks. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the practice of uroscopy was a central diagnostic tool for physicians.

Related: Hundreds of medieval skeletons, half of them children, discovered under Wales department store

"The patient's urine would be poured into a flask to allow a doctor to observe its color, sedimentation, smell, and sometimes even taste," project directors Rubina Raja, Jan Kindberg Jacobsen, Claudio Parisi Presicce and colleagues write in the study. Such analyses could shed light on whether patients had conditions such as jaundice, kidney disease or even diabetes, as diabetics' urine often smells and tastes sweet due to extra glucose.

Urine flasks are tough to identify in archaeological contexts because their shape is similar to oil lamps, and they are rare in contexts other than hospital dumps.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A final group of objects from the cistern included lead clamps from furniture fittings associated with carbonized wood, or wood treated with fire. These objects may be evidence of a historically known hygienic measure: the burning of objects from houses with plague cases, as written about in 1588 by Quinto Tiberio Angelerio, an Italian physician who published a series of rules for preventing the spread of disease.

Once full, the cistern was capped by a layer of clay, likely for hygienic reasons, the authors write. While landfills existed at this time outside the city walls of Rome, "the deposition of waste in cellars, courtyards, and cisterns, although prohibited, was a common practice," study lead author Cristina Boschetti, an archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark, told Live Science. In this case, the cistern may have been selected as a place suitable for sealing infectious waste, Boschetti explained.

Monica H. Green, a medical historian and independent scholar, told Live Science in an email that she agrees with the interpretation that the dump belonged to a hospital based on its "bespoke ceramicware."

Although we know today about the benefits of cooking or boiling glass to sterilize it, "people did not know the effects of sterilization at the time," Boschetti said. "They must have known that at least some kinds of glass could withstand cooking or boiling," Green agreed, but "that doesn't mean they nevertheless thought in terms of 'sterilization'."

While the medical dump found in the Forum of Caesar is actually the second example of hygienic disposal practices related to the Ospedale dei Fornari, little archaeological attention has been directed at other Renaissance-era hospital and medical contexts. The authors conclude that their study greatly helps our understanding of past practices "while highlighting the need for a more complete overview of the hygiene and disease control regimes of early modern Europe."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus