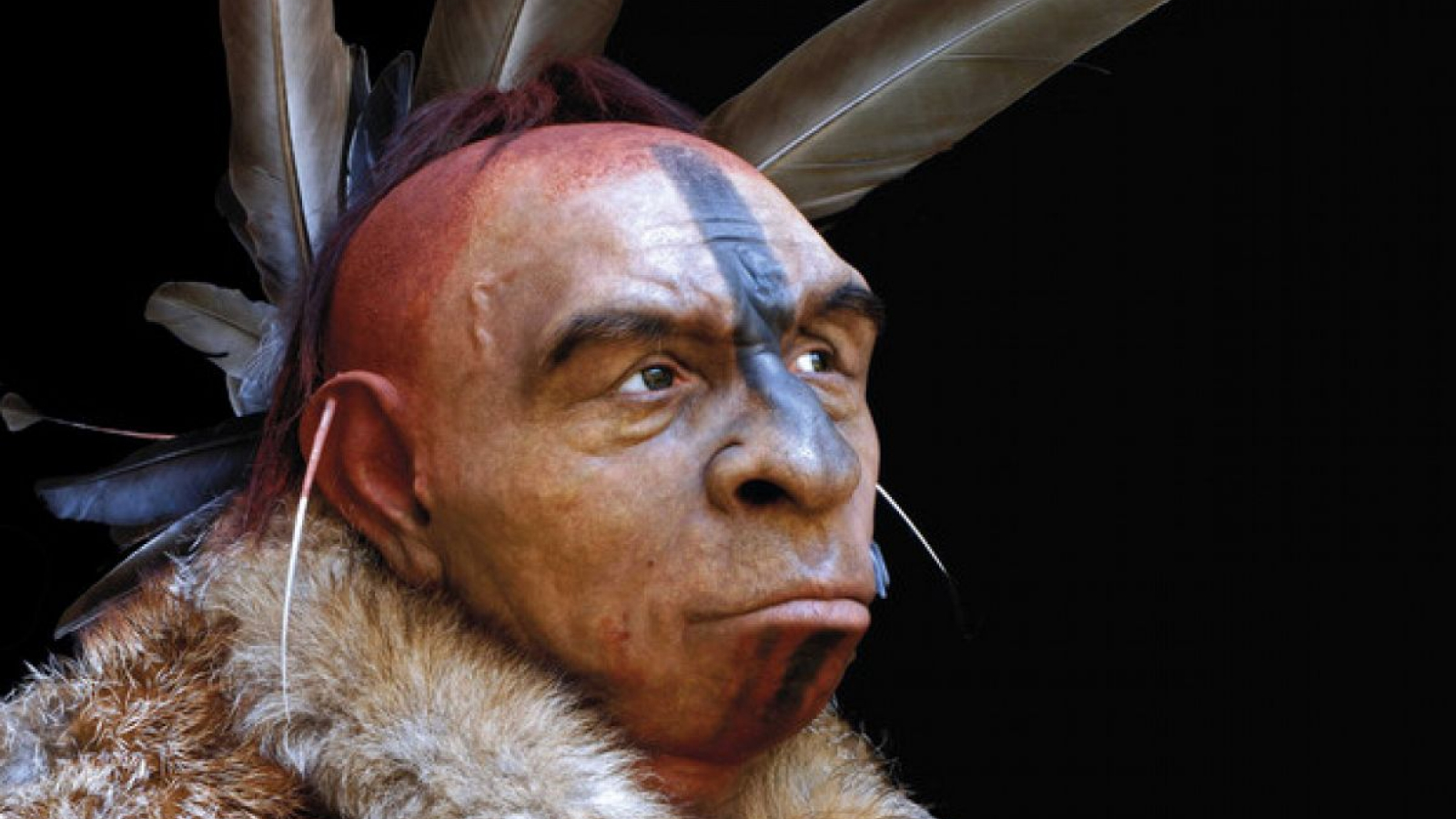

Neanderthals and modern humans interbred 'at the crossroads of human migrations' in Iran, study finds

A new ecological model suggests Neanderthals and modern humans interbred in the Zagros Mountains in what is now Iran before going their separate ways 80,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Modern humans and Neanderthals clearly interbred, genetic evidence shows, but exactly where and when has remained murky. Now, a new study pinpoints where one wave of those encounters occurred — the Zagros Mountains in what is now mostly Iran.

"The geography of the Iranian Plateau has been almost at the crossroads of human migrations," lead author Saman Guran, an archaeologist in the Institute for Prehistoric Archaeology at the University of Cologne in Germany, told Live Science in an email.

This region was a junction zone where the warmer ecosystems more hospitable to early modern humans transitioned to the colder climates that suited the Neanderthals, he added.

Neanderthals emerged around 400,000 years ago and lived in Europe and Asia, while the ancestors of modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and spread throughout the world. Genetic evidence suggests that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens came together multiple times — likely around 250,000 to 200,000 years ago, and then between 120,000 and 100,000 years ago, and finally, around 50,000 years ago — before Neanderthals disappeared as a distinct population.

Given the locations of archaeological sites with Neanderthal or early H. sapiens artifacts, the most likely place that these groups met was somewhere in the Middle East. But there is a distinct shortage of ancient human and Neanderthal bones from this area, meaning it's not currently possible to identify interbreeding through "hybrid" skulls or DNA.

To remedy this lack of information, the research team created an ecological model combined with geographic data pinpointing Neanderthal and human archaeological sites to reconstruct the most likely places where Neanderthals and modern humans overlapped during the second wave of interbreeding.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that modern humans and Neanderthals met — and potentially, interbred — in the Zagros Mountains, between 120,000 and 80,000 years ago. The team published their findings Sept. 3 in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Zagros Mountains extend 990 miles (1,600 kilometers) long and are located mostly in Iran. They are part of the Persian plateau, which was recently discovered to have been a "hub" for Homo sapiens around 70,000 years ago. But this area also had multiple ecosystems that could have supported both groups, the study found.

One of the most significant Neanderthal sites ever discovered, Shanidar Cave, is located in the Zagros Mountains. Ten skeletons have been found in this cave so far; several have signs of injuries, and others provide strong evidence that the Neanderthals buried their dead. However, most of the Zagros area has not been investigated.

"Archaeological data in this area is very poor," Guran said. "We have plans to get better evidence," he said, ideally the "recovery of physical human remains from archaeological excavations. Stone tools and better chronology are also a great help."

Did we kill the Neanderthals? New research may finally answer an age-old question.

The researchers' ecological model, which considered environmental variables such as temperature and precipitation, supplements the archaeological and genetic evidence of when and where Neanderthals and early humans mated.

"The approach used for the ecological models is similar to ours," Leonardo Vallini, a molecular anthropologist at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "However, we built ecological models only for Homo sapiens." The ecological overlap with Neanderthals in the Zagros Mountains "is a nice confirmation that the area could have played a crucial role in the earliest part of Homo sapiens' expansion into Eurasia," Vallini said.

This type of model can help archaeologists further narrow down the best places to dig in the future, the researchers suggested in their study. "We encourage Iranian archaeologists to conduct field excavations in this potential interbreeding area," they wrote, and "we await many exciting discoveries that will shed light on human evolution and dispersal."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus