Iron oxide baked into Mesopotamian bricks confirms ancient magnetic field anomaly

About 3,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, brickmakers imprinted the names of their kings into clay bricks. Now, an analysis of the metal grains in those bricks has confirmed a mysterious anomaly in Earth's magnetic field.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient bricks from Mesopotamia have helped confirm a mysterious anomaly in Earth's magnetic field that occurred 3,000 years ago, a new study finds.

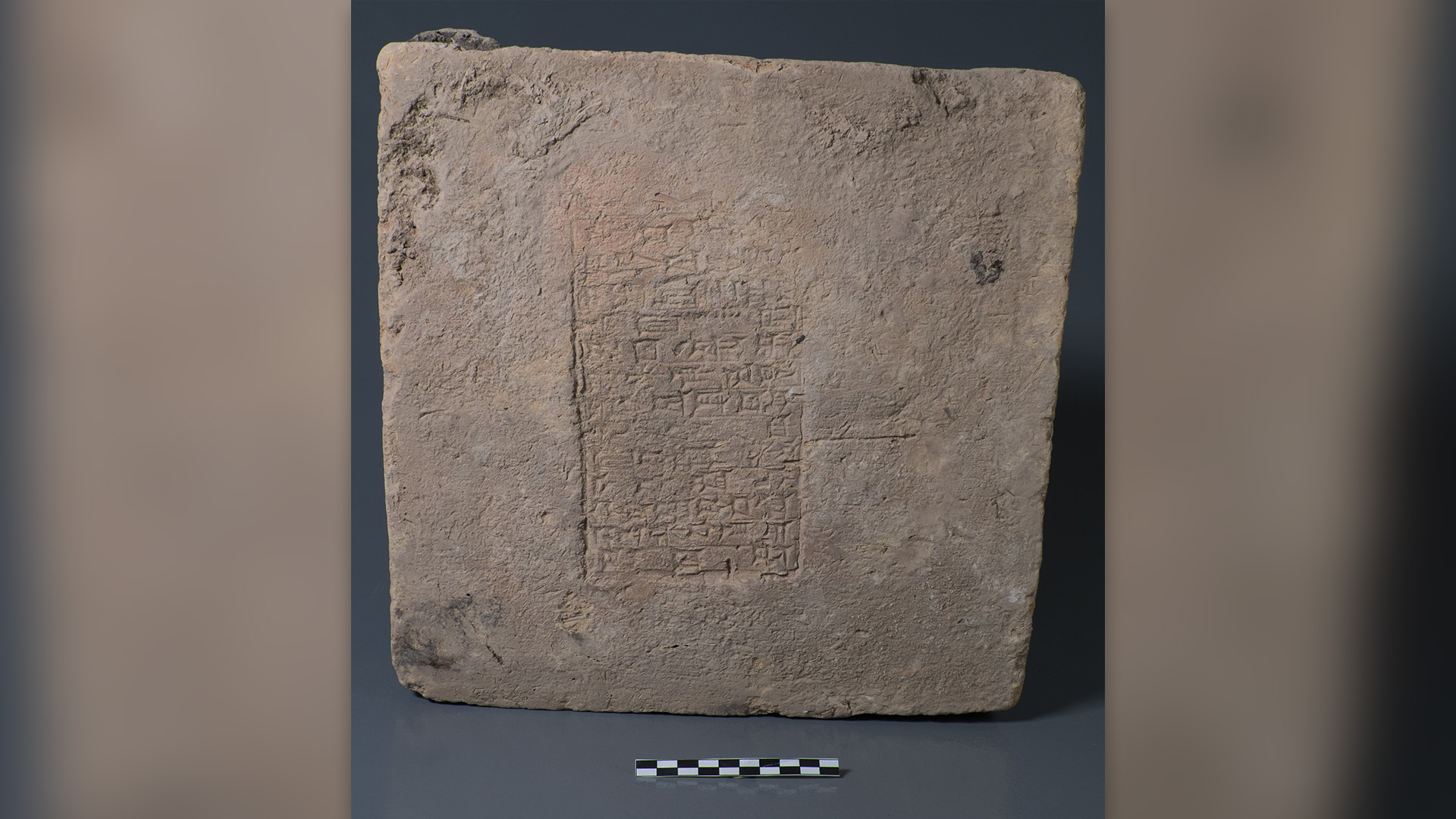

Brickmakers baked the bricks, which were imprinted with the names of Mesopotamian kings, between the third and first millennia B.C. Iron oxide grains within the clay recorded changes in Earth's magnetic field when the bricks were heated, enabling scientists to reconstruct changes in the magnetic field over time, the team reported in a study published in the journal PNAS on Monday (Dec. 18).

The finding may also help scientists date artifacts in the future, the team said.

"We often depend on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia," study co-author Mark Altaweel, a professor of Near East archaeology and archaeological data science at University College London, said in a statement. "However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot typically be easily dated because they don't contain organic material. This work now helps create an important dating baseline."

To investigate Earth's magnetic field — which waxes, wanes and even flips over time — the researchers looked at grains of the mineral iron oxide in 32 clay bricks from ancient Mesopotamia, located largely in what is now Iraq. These minerals are sensitive to the magnetic field, and when they are heated — for example when they are fired during brickmaking — they retain a distinct signature from Earth's magnetic field, the researchers said in the statement.

Related: Why do magnets have north and south poles?

Each brick was inscribed with the name of one of 12 Mesopotamian kings during each ruler's reign, which archaeologists already had dates for based on earlier findings. The team measured the magnetic strength of the iron oxide grains in each brick by chipping tiny fragments off the bricks' broken faces and using a magnetometer to measure the magnetic field strength of the minerals within. By combining the dates of the kings' reigns with the measured field strength, the researchers created a timeline showing the ups and downs of Earth's magnetic field over time in Mesopotamia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their research supported evidence for the "Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic Anomaly," a time when the planet's magnetic field was surprisingly strong around what is now Iraq between 1050 and 550 B.C. It's unclear why this anomaly existed during that period, but evidence for it has been detected as far away as China, Bulgaria and the Azores in the North Atlantic. Until now, evidence in the Middle East for the anomaly had been sparse, the researchers said.

In five of the samples, dating to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (circa 604 to 562 B.C.), the grains indicated that Earth's magnetic field shifted dramatically over the period.

"The geomagnetic field is one of the most enigmatic phenomena in earth sciences," study co-author Lisa Tauxe, a professor of geophysics at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, said in the statement. "The well-dated archaeological remains of the rich Mesopotamian cultures, especially bricks inscribed with names of specific kings, provide an unprecedented opportunity to study changes in the field strength in high time resolution, tracking changes that occurred over several decades or even less."

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus