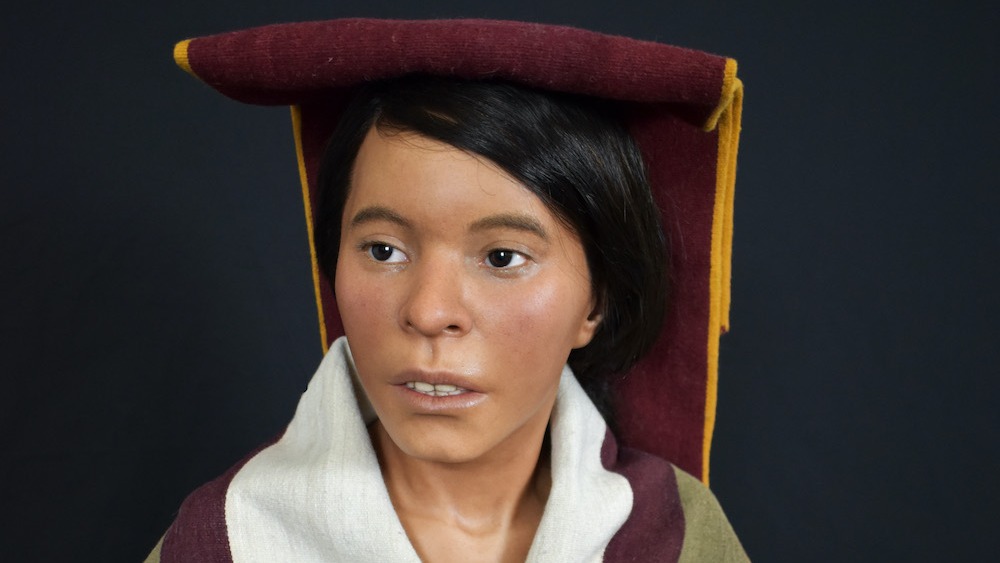

Incan 'Ice Maiden' who died in sacrifice 500 years ago revealed in hyper-realistic facial reconstruction

A new facial approximation brings to life an Incan girl who was killed 500 years ago as part of a sacrificial ritual.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than 500 years ago, an Incan girl was killed as part of a sacrificial ritual at a mountain summit in Peru. Her frozen mummified remains were discovered in 1995 by archaeologists, who named her the "Inca Ice Maiden" and "Juanita." However, no one knew what the mysterious girl looked like — until now.

To find out, Oscar Nilsson, a forensic artist based in Sweden, used a combination of computed tomography (CT) scans of skeletal remains, skull measurements and DNA analysis to create a hyper-realistic facial reconstruction of Juanita, Nilsson told Live Science in an email.

Nilsson teamed up with researchers from the Center for Andean Studies at the University of Warsaw and Museo Santuarios Andinosto in Cuzco to get a better idea of who Juanita was and what her life may have been like as an Incan youth. To do so, they investigated details from her frozen body, which archaeologists found during a trek up Ampato, one of the highest volcanoes in the Andes.

When researchers discovered her body, she was wearing a ceremonial tunic and a headpiece. Scattered nearby were female figurines made of gold and silver, woven bags, pottery and a shell. A CT scan of her skull revealed a "severe blow" to the back of her head.

The violent circumstances of her death led archaeologists to conclude that she likely died as part of a sacrificial ritual, according to an article in Expedition Magazine, which is published by the Penn Museum in Philadelphia.

"I was momentarily stunned when we lifted up the bundle and we found ourselves looking into the face of an Inca mummy," Johan Reinhard, the American archaeologist who found Juanita, wrote in the article.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These details about her discovery were crucial in informing Nilsson's work.

"To understand why she was found and placed long ago at the summit of a mountain, and to have some guidance in what could be said about the culture of the Incas, helped me in portraying her," Nilsson said. "It's of course extremely helpful to understand the context in a finding such as Juanita's."

To create the approximation, Nilsson started with CT scans of her skull and body provided by the archaeologists. He then transferred the data to a 3D printer to make a plastic replica.

"Before I started rebuilding the face, I needed to know the individual's age, gender, ethnicity and weight," Nilsson said. "These facts decide how thick the tissue depth would likely have been. … Juanita being from the Peru region, female and about 15 years old with no signs of malnutrition, would decide the tissue depth."

He then transferred these measurements to wooden pegs and used clay to build the details that defined Juanita's face. He was able to determine specific details about her nose, eyes and mouth by studying and measuring her nasal cavity, eye orbits and teeth.

Once the anatomical structure was in place, Nilsson worked on the tiny details that helped bring her back to life, including creating "small expressions" on her face that "retained the scientific correctness" from the scans, he said.

"In Juanita's case, I wanted her to look both scared and proud, and with a high sense of presence at the same time," Nilsson said. "I then cast the face in silicone [using] real human hair [that I] inserted hair by hair." Her DNA helped define the color of her skin, “with the face pigmented to look like real skin."

The final touch of the reconstruction was to dress her in clothing similar to that found on her mummy.

The result is an incredibly lifelike silicone bust of an Incan teenager with high cheekbones and dark hair and eyes.

"I thought I'd never know what her face looked like when she was alive," Reinhard told the BBC. "Now 28 years later, this has become a reality thanks to Oscar Nilsson's reconstruction."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus