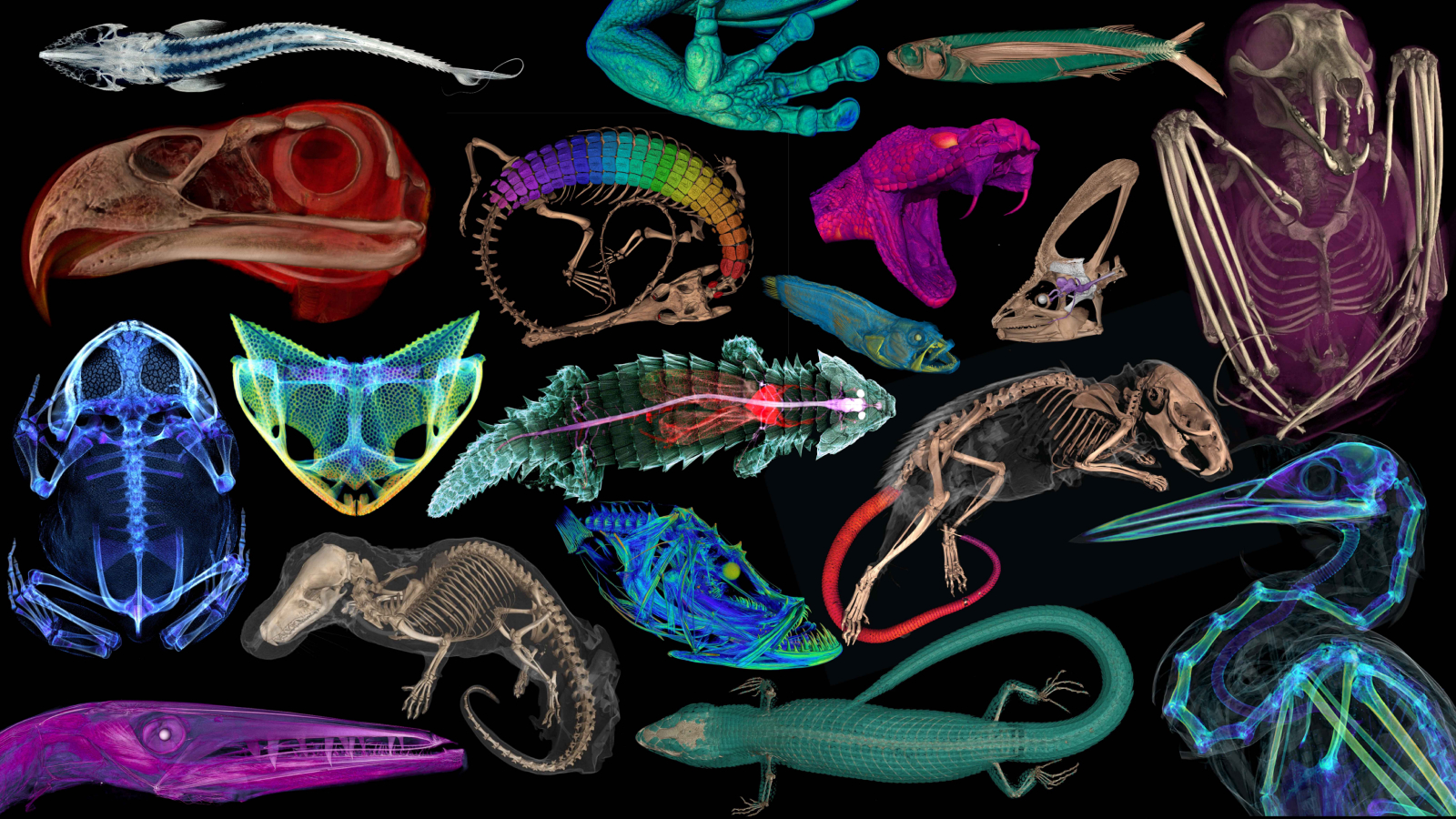

Striking virtual 3D scans reveal animals' innards — including the last meal of a hognose snake

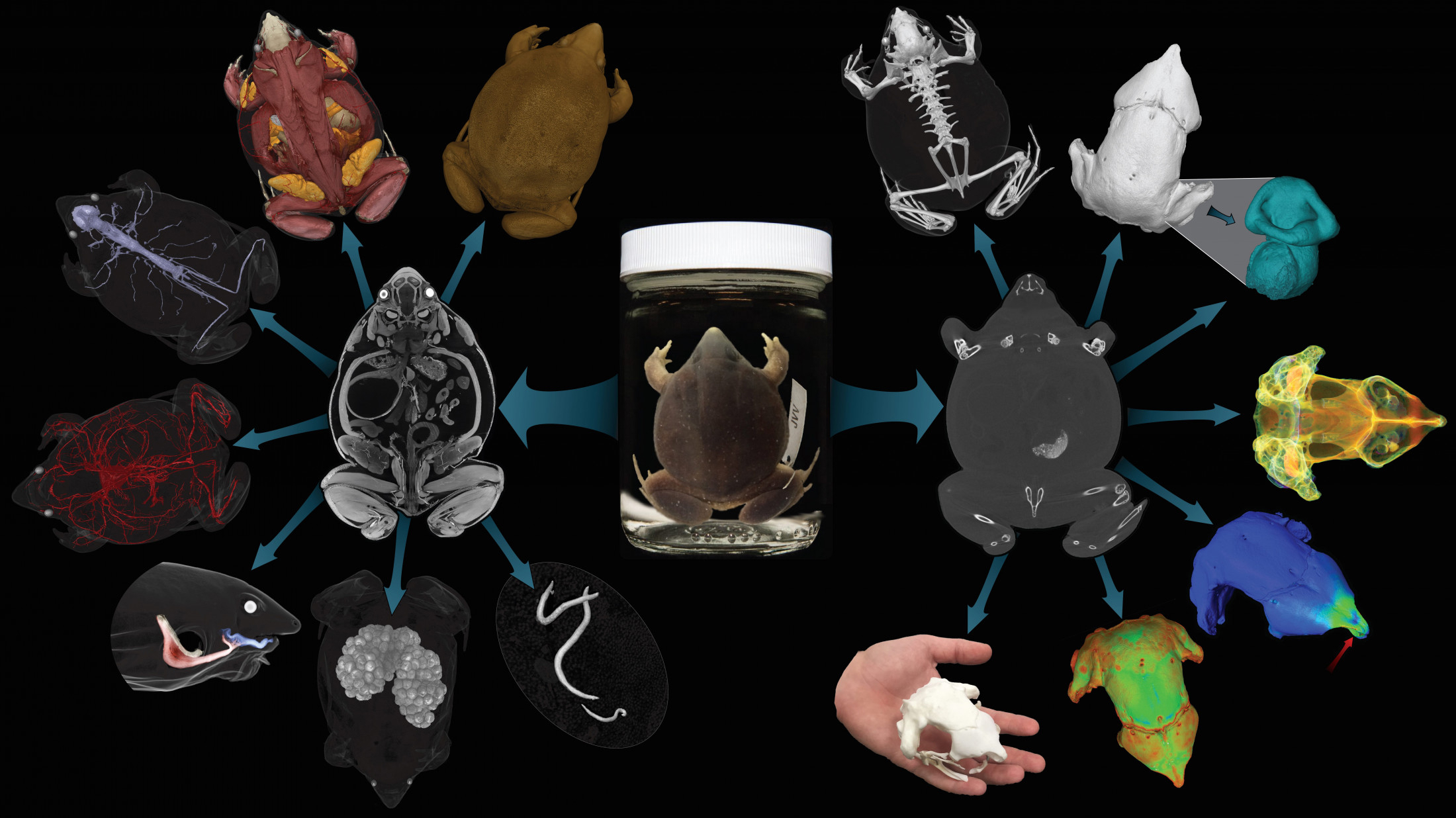

3D reconstructions of over 13,000 specimens have been collected as part of a collaborative project called openVertebrate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Incredible 3D images of over 13,000 vertebrates — representing half of the world's described genera — have been created as part of a project to make museum specimens available to all.

From spine-tailed mice (Acomys species) to rare rim rock crowned snakes (Tantilla oolitica), natural collections from museums around the world are being added to openVertebrate (oVert) — a five-year project funded by the National Science Foundation creating a database of computed tomography (CT) scans of specimens.

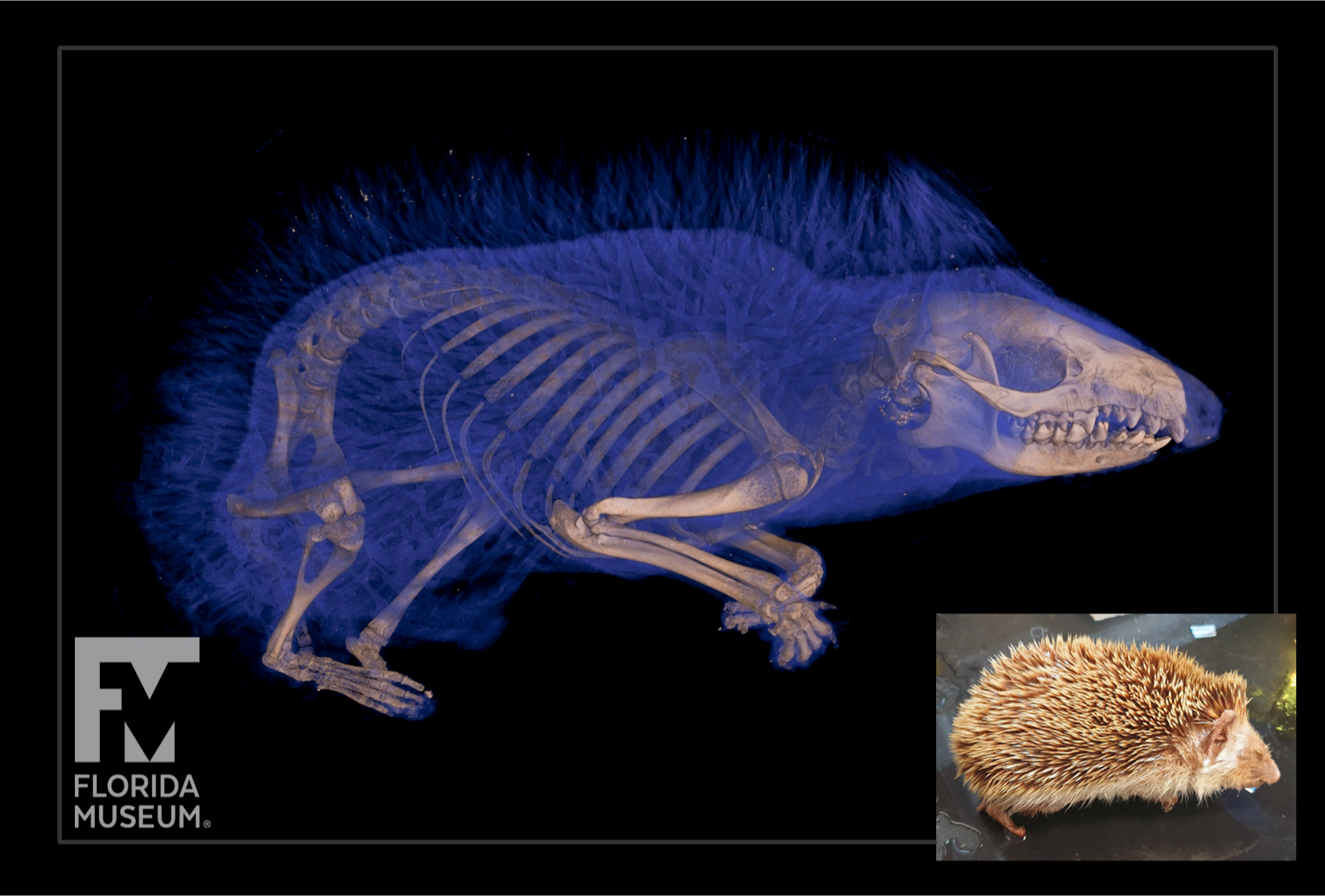

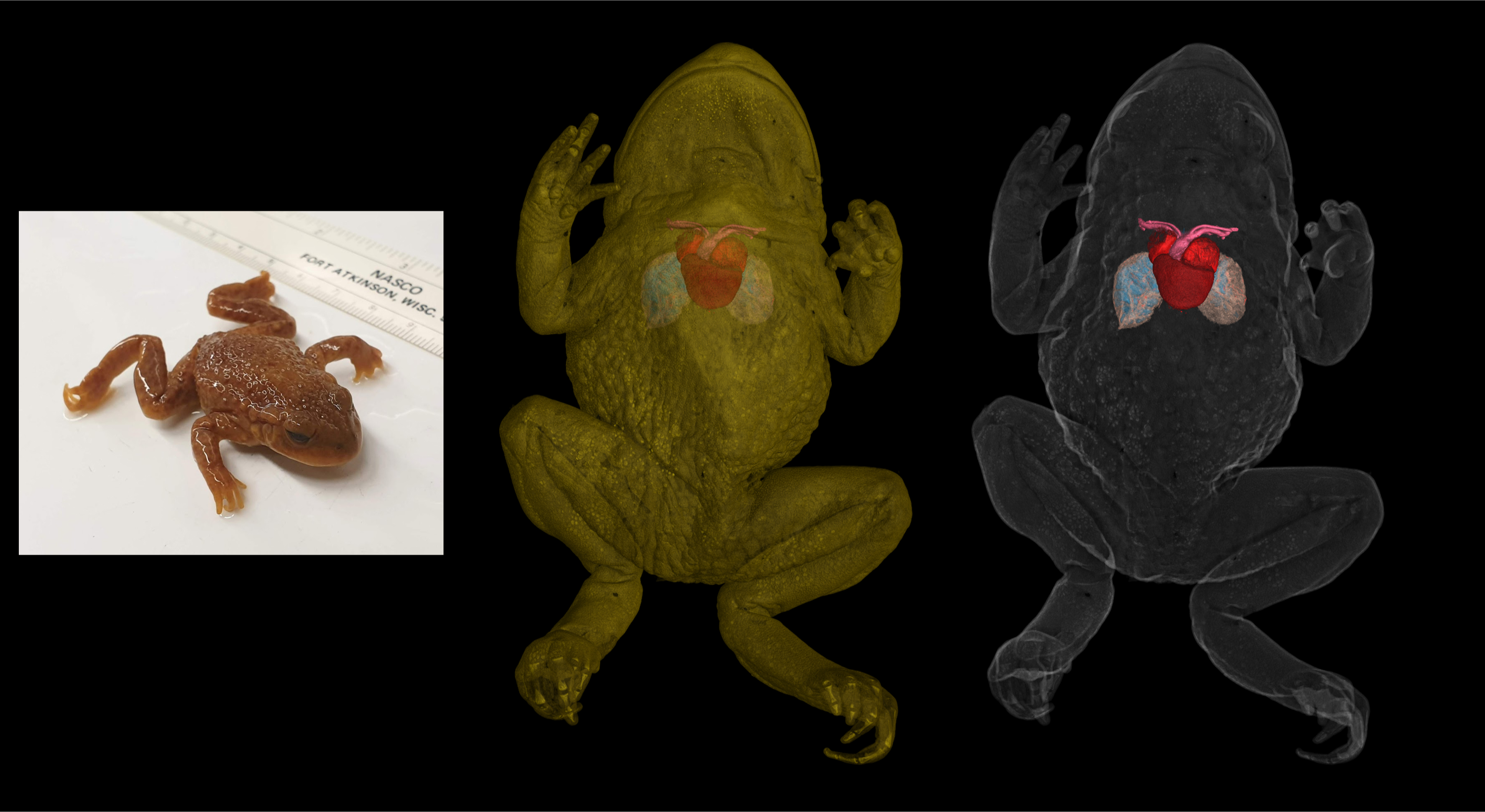

CT scans combine multiple X-ray images taken from different angles around the body to create detailed cross-sectional images, enabling scientists to peer through the exterior of animals without damaging the specimens. This gives them valuable insight into skeletal structures.

Some specimens were even stained during scanning so researchers could view soft tissue structures, revealing stomach contents, eggs, parasites and organs.

As of November 2023, 13,000 specimens across 18 U.S. institutions have been scanned.

Related: 3D scans reveal that beetles have secret pockets on their backs

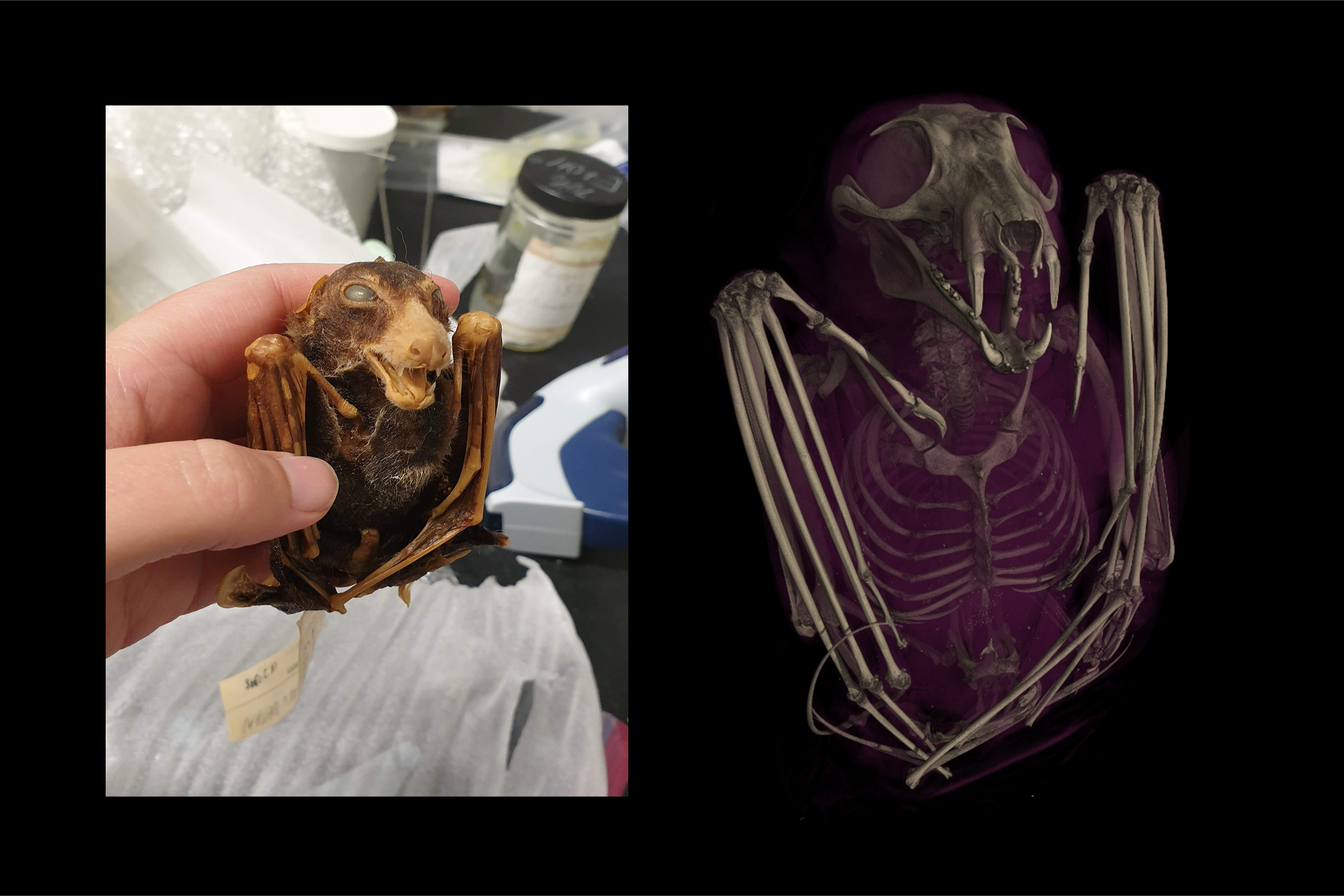

The project team has released a selection of images from the project showing creatures in remarkable detail. These include a CT scan of the final meal of a hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos), the prickly spines of a four-toed hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) and a black-bellied fruit bat (Melonycteris melanops).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When first created, museums held rare specimens as part of private collections of wealthy individuals. Now, museums are open to the public, but some collections remain concealed.

"Access to these collections is often limited; cost of travel, space restrictions, fragility of specimens, all can prevent people from working with these samples," Edward L. Stanley, an author and Director of the Digital Imaging Division at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told Live Science in an email.

Stanley is an author of a study published Mar 6. in the journal BioScience that provides a summary of the project to date.

Studying specimens often involves dissections and chemical testing, which can damage specimens, further limiting accessibility. "Museums have to strike a balance between using their specimens and using them up, which often means that rarest and most important specimens are often the hardest to access", Stanley said.

"The digital data from CT scanning provides a fast and low-risk way for museums to make even their most delicate, rare or irreplaceable specimens available to anyone, anywhere in the world," Stanley added.

Elise studied marine biology at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. She has worked as a freelance journalist focusing on the aquatic realm.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus