'Hostilities began in an extremely violent way': How chimp wars taught us murder and cruelty aren't just human traits

"These primates' fierce battles were instigated by coalitions of adult males, with the sole aim of extending their territory. The areas where the fighting took place corresponded to the land conquered by force."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

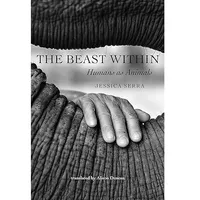

War and violence can often seem like uniquely human acts that have been present for most of our recent history. But do other animals wage "war"? In this excerpt from "The Beast Within: Human as Animals" (2024, Johns Hopkins University Press), scientific researcher Jessica Serra looks at the dark side of chimpanzees' (Pan troglodytes) behavior to show that our closest living relatives also have a taste for warfare.

Among nonhuman mammals, hostility between rival groups is quite widespread, but it rarely leads to death. The frequent fighting between males is most often limited to intimidation behavior. While certainly frightful, it is rarely fatal. There is one exception, however: our closest cousins, the chimpanzees! Ethological studies have shown animals to be capable of forming complex political alliances. English primatologist Jane Goodall made a major discovery on this subject when she revealed an unsuspected dark side in chimpanzees.

In 1974, when Goodall was studying the behavior of chimpanzee colonies in Gombe, Tanzania, she observed a social divide between two groups in one of the communities. The first group, called the Kasakela community because they occupied the north part of the park bearing this name, was composed of eight adult males and twelve adult females, as well as their young. The second group, called the Kahama community, consisted of six adult males, an adolescent male and three adult females.

The hostilities began in an extremely violent way when a male from the Kasakela group killed Godi, a male from the Kahama group. The rage of the Kasakelas continued to plague the Kahamas for the next four years, during which time six more males were killed. As for the Kahama females, two disappeared and three were beaten by a gang of violent males.

The end of this "four-year war" resulted in the Kasakela community taking over the Kahama's territory. It was a short-lived victory, however, since another community of chimpanzees living nearby managed to scare the Kasakelas away.

Goodall recounted her poignant memories of this war in her memoir "Through a Window: My Thirty Years with the Chimpanzees of Gombe." She recalls, "For several years I struggled to come to terms with this new knowledge. Often when I woke in the night, horrific pictures sprang unbidden to my mind — Satan [one of the apes], cupping his hand below Sniff's chin to drink the blood that welled from a great wound on his face; old Rodolf, usually so benign, standing upright to hurl a four-pound [1.8 kilograms] rock at Godi's prostrate body; Jomeo tearing a strip of skin from Dé's thigh; Figan, charging and hitting, again and again, the stricken, quivering body of Goliath, one of his childhood heroes."

Related: Chimps use military tactic only ever seen in humans before

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jane Goodall is not the only one to be haunted by the bloody images of murders between groups of chimpanzees. American researchers reported similar scenes of violence among chimpanzees in Kibale National Park in Uganda. These primates' fierce battles were instigated by coalitions of adult males, with the sole aim of extending their territory. The areas where the fighting took place corresponded to the land conquered by force.

Are these primates really at "war"? If we define war as being lethal violence organized against members of another group, then the answer is clear. Like humans, chimpanzees have the capacity to wage war. Before the fighting began in Kibale National Park, the males carried out systematic patrols. The location of the corpses confirms the importance of the territory as a motivation to fight: these chimpanzees had breathed their last breath in this coveted neighboring area. These wars were fraught with the terror of infanticide between rival gangs, atrocities also committed by humans.

Three such attacks were reported by anthropologists from Ohio University and the University of Michigan in the International Journal of Primatology. The researchers recounted how on different occasions, while on patrol, the adolescent and adult males of the Ngogo chimpanzee community attacked the children of a rival gang, killed them, and cannibalized one of them.

Although there are cultural disparities between our ways of waging war and those of chimpanzees, certain similarities are striking. Both humans and chimpanzees ensure that assassinations can be committed by several individuals without major risk to the assailants, and both have motivations for these killings (gaining territory, hierarchical position, access to resources, etc.). In fact, some researchers are now using the "chimpanzee model" to explain the emergence of war in humans.

But aggression in chimpanzees does not only manifest itself when faced with a rival community. American anthropology professor Jill Pruetz and her team at Iowa State University recounted the 2013 murder committed by several males of a member of their own group at Fongoli in Senegal. While the researchers did not witness the massacre as it took place, which was in the darkness of night, they did hear the blood curdling cries. In the morning, they discovered with horror the corpse of Foudouko, a 17-year-old former alpha male, who had been stripped of his status in 2007 by a gang of young chimpanzees.

Condemned to exile and isolation, the pariah regularly attempted to rejoin the group, imposing himself as dominant, which the new alpha males did not like. The research team speculated that if his entrance had been more submissive, the outcome would probably not have been fatal. These lethal attacks recorded in chimpanzees, rare but incredibly cruel, were not linked to a human presence near their communities (as some scientists had presumed) but to a hierarchical tension within the group and probably to intense competition for access to females.

But what disturbed scientists the most was how the gang treated Foudouko's body the day after his death. Most likely to make sure they had nothing left to fear, the murderous gang dragged the body across the ground, sniffed it repeatedly, ripped out its genitals, bit it all over, and tore its flesh and… ate it!

Murder and cruelty are therefore not unique to H. sapiens. And the animal world has not finished surprising us either.

Excerpted from The Beast Within: Human as Animals, by Jessica Serra. Copyright 2024. Published with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

The Beast Within: Humans as Animals - $19.95 at Amazon

Are humans the only creatures who love, laugh, cry, possess morals, and wage war? In The Beast Within, scientific researcher and ethologist Jessica Serra upends the assumptions that underpin our very human hypothesis that we possess a superior place in the hierarchy of organisms on Earth. How did we come to think of our animality as standing in opposition to our humanity―and does this reasoning have a scientific basis?

Jessica Serra is a scientific researcher, writer, editor, and consultant. She is the author of The Secret Life of Cats, which became the basis for popular French television show, La Vie Secrète des Chats on BBC Worldwide.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus