Ancient Maya power broker died in obscurity, hieroglyphics show

The ancient Maya ambassador had pyrite and jade implants in his teeth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

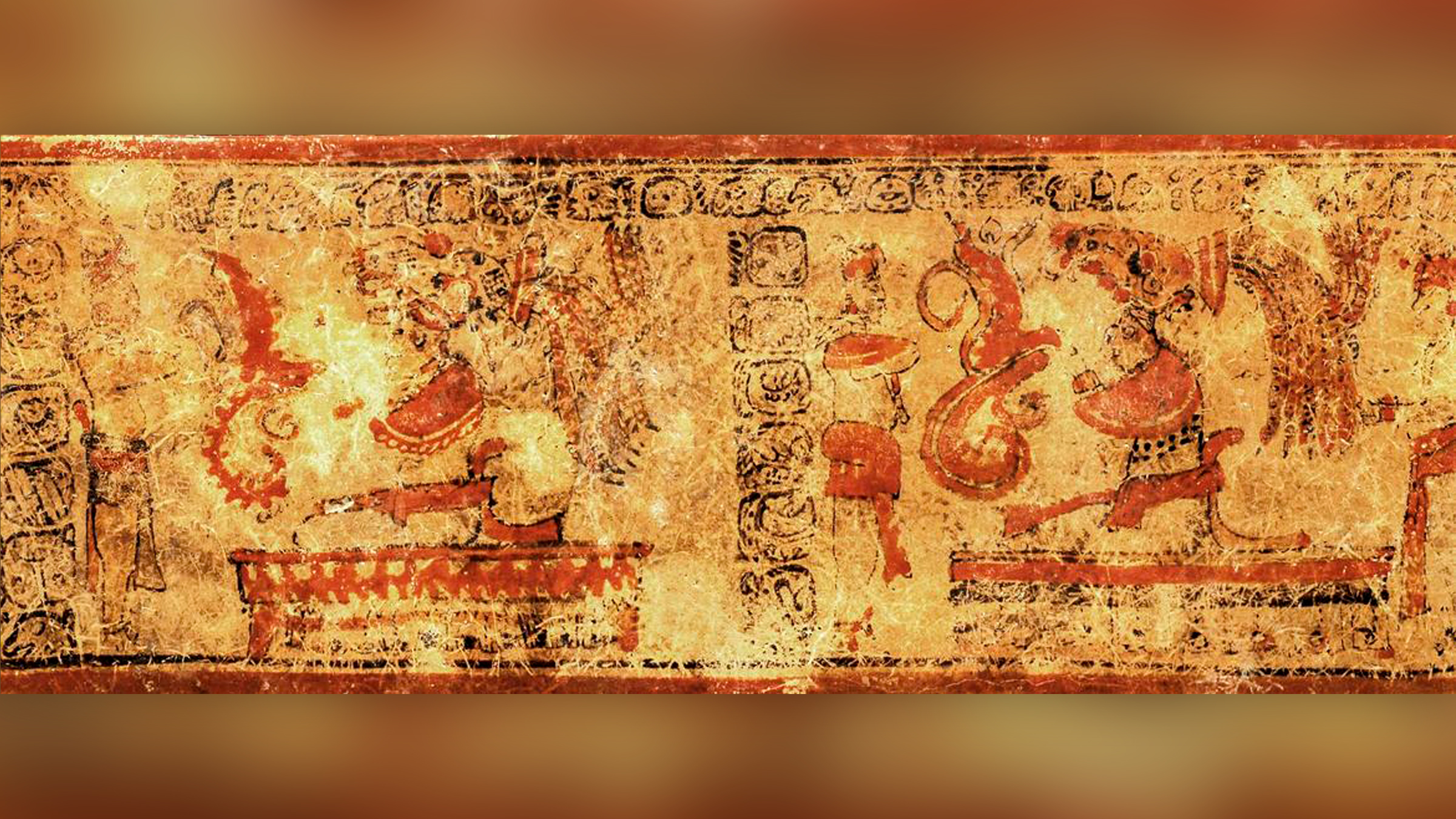

Ancient hieroglyphics painted in a stairway near a Maya ambassador's burial tell the tale of his elite but tumultuous life nearly 1,300 years ago, a new study finds.

The ambassador, a man named Ajpach' Waal, helped broker an alliance between two powerful dynasties — the Maya king of Copán, in modern-day Honduras, and the Maya king of Calakmul, in present-day southern Mexico, according to the hieroglyphics. But when the alliance fell through, Ajpach' Waal's fortunes tanked and he died in relative obscurity.

The finding reveals that playing politics could elevate or plummet the standing of "a nonroyal elite of Late Classic period Maya society (A.D. 600–850)," the researchers wrote in the study, adding that "little is known about their life experiences and mortuary practices."

Related: In photos: Hidden Maya civilization

Archaeologists found the unique stairway and burial while excavating a Maya plaza in El Palmar, Mexico, near the borders of Belize and Guatemala. Once the team translated the hieroglyphics found in the stairway, they learned that the man buried there had traveled 350 miles (560 kilometers) in A.D. 726 to meet with the king of Copán, in the hopes of forging an alliance between Copán and the king of Calakmul, near El Palmar.

The hieroglyphics referred to Ajpach' Waal as a "lakam," an ambassador who carried a banner as he walked between cities on diplomatic missions. Ajpach' Waal inherited this position from his father, and, according to the hieroglyphs, his mother also came from an elite, nonroyal family. The hieroglyphics also noted that Ajpach' Waal built the platform where he was ultimately buried shortly after his 726 mission. Such platforms could be built only by powerful individuals, and they were often used as stages where audiences watched rituals.

Study senior researcher Kenichiro Tsukamoto, the head of the archaeological excavation and an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of California, Riverside, found the ancient ambassador's burial in a small chamber under the floor of a temple adjacent to the platform.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, despite Ajpach' Waal's elite status, he was buried with only two decorated clay pots. An analysis of his teeth and skeletal remains also suggested he was ill or malnourished as a child, and that, as an adult, he experienced health problems, including arthritis and dental troubles.

"His life is not like we expected based on the hieroglyphics," Tsukamoto said in a statement. "Many people say that the elite enjoyed their lives, but the story is usually more complex."

Elite appearance

The skeleton buried in the chamber, who is likely Ajpach' Waal or his esteemed father, died between the ages of 35 and 50, a bone analysis showed.

Whoever he was, the man had a ritzy smile. His upper front teeth had been drilled to hold decorative implants made of pyrite and jade — valuable and regulated minerals at that time — the researchers found. Certain Maya elites often received these dental implants when they reached puberty, the researchers noted.

The back of the man's skull was mildly flattened, a characteristic that develops when babies' heads are placed against a flat surface for long periods and was considered attractive among the Maya at the time. The front of the man's skull was not preserved, so the researchers don’t know if it was flattened, too, although this frontal-flattening practice was limited to royal Maya individuals, Tsukamoto and study lead researcher Jessica Cerezo-Román, an assistant professor of anthropology at The University of Oklahoma, found.

Related: Maya Mural reveals ancient 'photobomb'

The man's remains showed signs of dental problems, including teeth lost to gum disease. In addition, his arms had evidence of healed periostitis (inflamed connective tissue near the bone), possibly caused by bacterial infections, trauma, scurvy or rickets, the researchers said. Moreover, both sides of his skull had porous, spongy regions, indicative of a condition called porotic hyperostosis that is caused by nutritional scarcity or illness in childhood, the archaeologists said. This condition is found in the remains of many Maya individuals, but it's interesting that this man's elite status didn't protect him from developing it, the researchers said.

The man also had healed fractures on his right shinbone, possibly from playing the Maya's famous ballgame, the researchers said. The arthritis in his hands, elbow, knee, ankle and feet might have been caused by the banner he had to carry on his diplomatic missions, they added.

These health problems weren't the man's only worries.

"The ruler of a subordinate dynasty decapitated Copán's king 10 years after his alliance with Calakmul, which was also defeated by a rival dynasty around the same time," Tsukamoto said. "We see the political and economic instability that followed both these events in the sparse burial and in one of the inlaid teeth."

An analysis of the man's right canine tooth revealed that one of the inlays had fallen out, which would have left an embarrassing hole that would have been visible when he talked. The inlay was not replaced, according to an examination of the dental plaque that had hardened into calculus in the hole. Perhaps this man's usefulness as an ambassador was dismissed, in part, because of his bad teeth, the researchers said.

The Maya continued living in El Palmar after the man died, but it didn't last long; eventually, the city was abandoned and the jungle reclaimed it, the researchers said.

The study was published online Feb. 17 in the journal Latin American Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus