Scientists Create Clear Image of Tiny Molecule

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

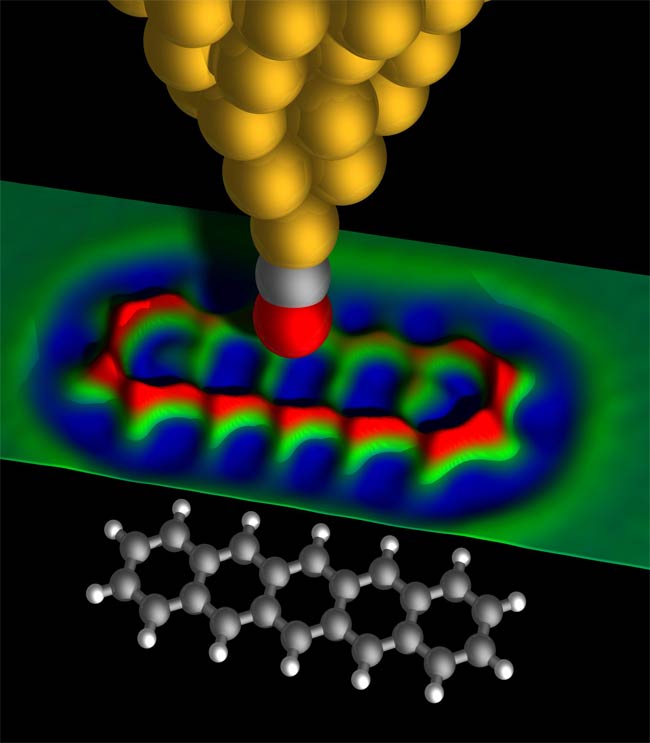

A new imaging technique has brought into focus the anatomy of a hydrocarbon molecule, revealing its tiny atoms and their bonds.

The molecule, called pentacene, is made up of five ring-like structures composed of carbon and hydrogen atoms.

"We can see all the atoms within the molecule," lead researcher Leo Gross of IBM’s Zurich Research Laboratory in Switzerland told LiveScience. "We can even see the carbon-hydrogen bonds and deduce the position of the hydrogen atoms. These are very hard to image, because they are so small."

(Each atom is about a million times smaller than a grain of sand.)

Until now, images of such molecules have been relatively blurry. In the Aug. 28 issue of the journal Science, Gross and his colleagues report the key to cutting through this blur is the probe tip of a so-called atomic force microscope.

The microscope uses a sharp-tipped probe that scans a molecule line-by-line, measuring changes in force between the tip and a spot on the molecule. Traditional metal tips, however, actually stick to the molecule they are scanning. So Gross's team used a carbon monoxide tip, which can get extremely close to the molecule (much less than a hair-width distance) without attaching to it.

The result is roughly a three-dimensional map of pentacene.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- 10 Profound Innovations Ahead

- All About Nanotechnology

- Microscopic Images as Art

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus