Bio-Art: 'Blood Quran' Causes Controversy

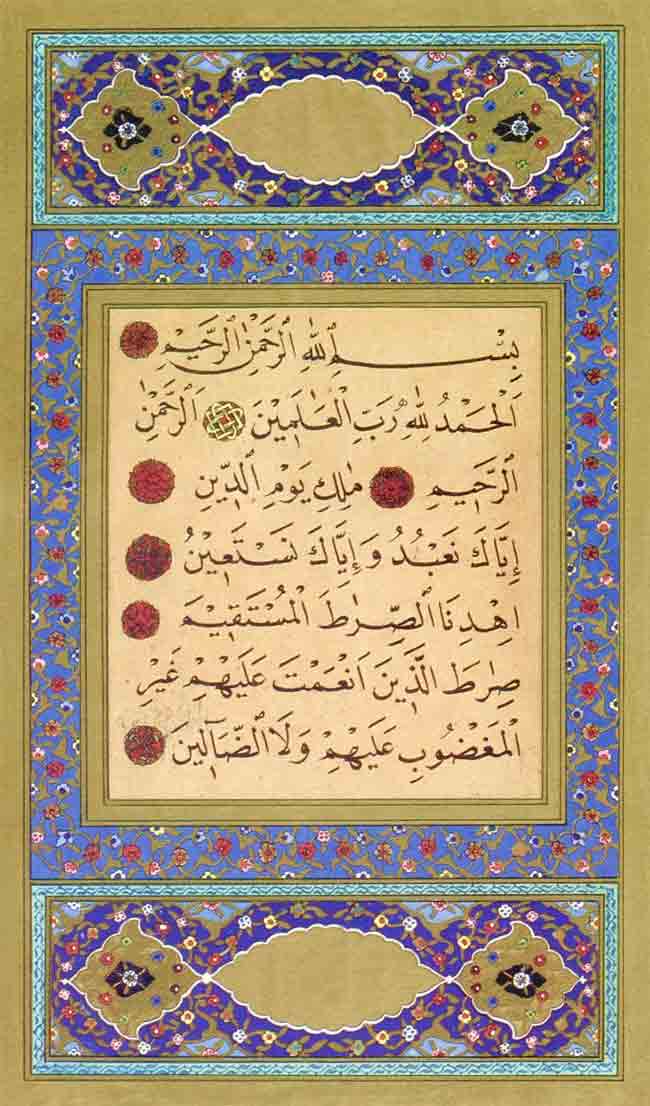

A Quran written in Saddam Hussein blood is a macabre reminder of the dictator's brutal reign. According to art experts, it's also both a continuation of — and a departure from — artistic tradition.

The "Blood Quran" is taking a toll on Islamic clerics uncertain of whether it's better to destroy the holy book or preserve it as a reminder of the dictator's brutality. Hussein likely knew the controversy his blood-inscribed Quran would create when he commission it, given common taboos surrounding human bodily fluids. But despite the shock value of a book written in human blood, animal blood has been a part of art for centuries.

"Blood is a common medium used in paint," Bruno Pouliot, an objects conservator at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware and a professor of art conservation at the University of Delaware, told LiveScience. "Ox blood is one of the oldest forms, and a very stable form, actually, of paint."

Bloody but sacred

In the late 1990s, Hussein conscripted a calligrapher to copy the Quran in his blood. In what he reportedly described at the time as a gesture of "gratitude" to God, Hussein donated seven gallons (27 liters) of blood over the course of two years to be used as ink in the macabre volume, according to an article in The Guardian on Sunday (Dec. 19).

The Quran is now kept behind locked doors in a mosque in Baghdad, and officials are uncertain how to handle an object that is simultaneously sacred and profane.

"What's different about things that involve human remains is that they are always controversial," University of Delaware professor of art conservation Vicki Cassman told LiveScience. In the case of the Quran, Cassman said, "there is that symbolism — that is, who it represents and if this person's spirit lives on in the object."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While blood art may raise a host of ethical issues, the practical concerns aren't great, Pouliot said. As blood dries, it forms a solid film — think how difficult it is to get a bloodstain out of fabric.

"You have to process it a little bit to get it to have the exact properties that you need, but it's a relatively easy process that anybody who could search online or would have access to the historical recipe for oxblood paint could do," Pouliot said, minutes before pulling up an oxblood paint recipe online involving linseed oil and lime.

Body art

Should the Iraqis choose to preserve the Quran, they likely won't have to take many extra precautions in terms of preservation, Pouliot said. Regular book preservation should do.

"Climate control is the first step," said Jim Hinz, the director of book conservation at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in Philadelphia. Humidity and temperature are key, he said, with cooler temperatures being better. Books should also be kept out of direct light, he said.

Hinz said he had not worked with any artwork made with blood, but he did have a tip for anyone who bleeds on something important: Spit.

"The enzymes [in saliva] break down and essentially bleach out the blood," he told LiveScience.

The big questions that come up with the preservation of biological art aren't technical, Pouliot said. Instead, they're ethical. Conserving art sometimes involves applying stabilizing resins.

For blood, "there could be many reasons why it would not be desirable to change the composition of that material, in case it is useful for future studies," Pouliot said. "Often the cultural aspects of that object become important."

Human hair and even human skin show up in art throughout the ages, Pouliot said, but human blood has been much more rare. More recently, some modern artists have taken to including blood in their work, including British artist Marc Quinn, who sculpts his head out of about a gallon (4.5 liters) of his own frozen blood every five years.

Risky medium

Pouliot credits the relative lack of blood-containing artwork to cultural taboos around the liquid.

"These taboos are often related to actual risks involved in using these materials," he said.

Those risks include blood-borne diseases like Ebola, hepatitis B and HIV, said Celso Bianco, the executive vice president for America's Blood Centers, a network of nonprofit community blood donation centers. Hussein's calligrapher would have been at risk for contracting disease from the fresh blood, Bianco said, but that concern is long gone.

"The pathogens that can be carried with blood are many." Bianco told LiveScience. "But in general, when it's dried in the form of the written word, they would not be dangerous. They would not be infectious."

Perhaps the biggest health risk came for Hussein himself, whose 27-liter blood donations over two years would have been roughly five times the amount of blood in his body at any given time, Bianco said.

The amount of donation allowed for a blood donor in the United States is five or six pints over the course of a year, or less than a gallon, Bianco said. At that safe rate, it should have taken Hussein nine years to donate all that blood, not two.

"It's an incredible amount, if that [number] is correct," Bianco said. "That certainly would have made him anemic."

- Gallery: Art Meets Science in Amazing Images

- Understanding the 10 Most Destructive Human Behaviors

- What Science and Art Have in Common

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus