No Fair! Kids and Adults View Fairness Differently

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What we consider "fair" changes as we age, a new study finds. Young children like all things to be equal, but older adolescents are more likely to consider merit when it comes to dividing up wealth, the researchers say.

The shift from the "egalitarian" view of fairness to the more merit-based "meritocratic" view occurred largely between fifth and seventh grade, although it continued to change through high school, with seniors placing the most importance on achievement.

This transition likely results both from changes in the brain as it develops, and from exposure to new social experiences as we age, the researchers say. For instance, children might participate in more and more activities in which a greater emphasis is placed on individual achievement as they grow up.

A better understanding of what people think is fair, and how this perception develops, might lead to changes in how institutions, such as schools, are set up, said study researcher Ingvild Almas, of the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration in Bergen, Norway.

"The idea that social experiences contribute to shape our views on fairness is fundamental to how we design optimal policies and institutions in society such as the educational system," Almas told LiveScience. For example, it might be the case that schools should not give academic grades to children when they are very young if grades based on merit do not fit with the fairness views of the children, Almås said.

Previous work has shown that most adults think some inequalities are OK when it comes to divvying up income. For instance, they think that differences in what people have accomplished can justify an unequal split of money. Or a less than even distribution might be OK if it means the total income for everyone is larger. However, adults don't agree on whether differences in luck are an OK source of inequalities.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

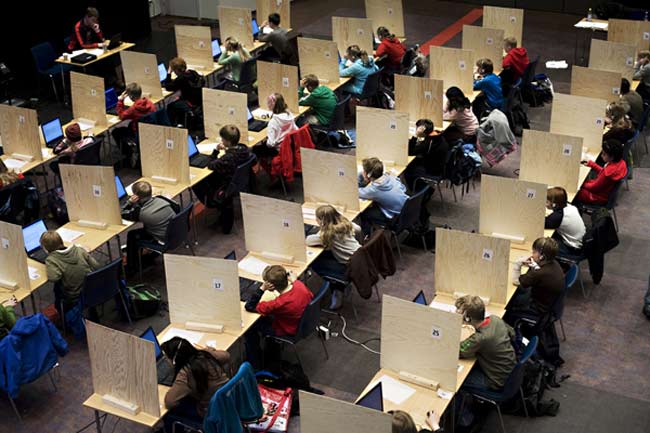

Almas and her colleagues wanted to know when exactly these views on fairness develop. They recruited 486 children from 20 schools in Norway in grades 5 through 13 (some high schools continue through grade 13 in Norway).

The children played two different games designed to tease out exactly what goes into deciding what is considered fair.

In one scenario, the kids played an online game in which they could collect points by finding certain numbers within a number sequence. They also had the option of going to a different website where they could view pictures, videos and cartoons and play games, but did not get points. This element of the experiment meant there would be differences in the children's achievement.

Their total score was then assigned a monetary value, with each point worth $0.08 (0.4 Norwegian Kroner, or NOK) or $0.03 (0.2 NOK). This added an element of luck to the game.

Then, children were paired up and asked to decide how to distribute their wealth. They were made aware of all the information about their partners’ scores, earnings and time they spent playing the points game.

The researchers looked for three types of views on fairness: egalitarianism (those who believe all inequalities are not fair), meritocratism (those who think inequalities regarding differences in achievement are OK) and libertarianism (those who think that all inequalities are OK).

Almost all the fifth graders were egalitarians, with very few meritocrats. The proportion of egalitarians fell as children got older, with most in late adolescence adopting a meritocratic point of view. The proportion of libertarians did not change much over all grade levels.

In a second game, children where simply given a certain number of points and asked to distribute them between himself or herself and a partner. However, they were told that each point they kept for would be worth $0.15 (1 NOK), while each point given away would count as $0.15 multiplied randomly by 1, 2, 3 or 4 for the other participant. This was done to look at so-called "efficiency considerations," or how to distribute something so that the total income is maximized.

Children in fifth and seventh grades didn't appear to care significantly about maximizing their total income, according to Almås. However, later in adolescence, around the age of 16, it started to matter, particularly for male students, Almås said. "So this development happens later," she said.

The older children's views on fairness match up quite well with those of adults, Almås said, making the researchers more confident that they actually have captured the progression of these views as people age. Like adults, older children give more weight to achievements and less to luck when it comes to deciding how to divide up money.

The results will be published May 28 in the journal Science.

- Top 7 Ways the Mind and Body Change With Age

- Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special

- Why We 'Play Nice' With Strangers

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus