Biden Promises to 'Cure Cancer' If Elected. Here's Why That's Laughable.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

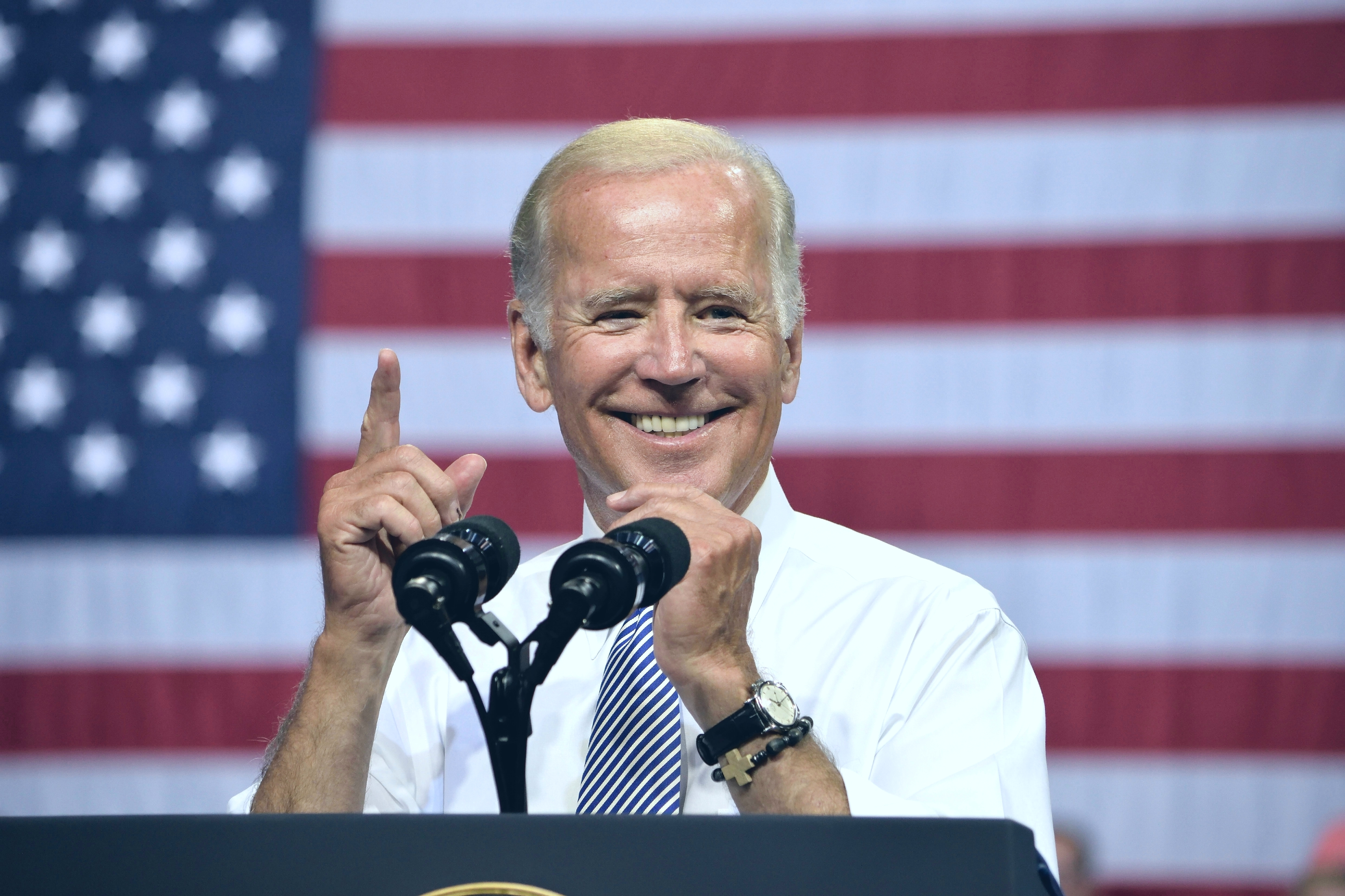

If former Vice President Joe Biden gets elected in 2020, he's curing cancer. At least that's what the presidential hopeful promised at a campaign stop in Ottumwa, Iowa, on Tuesday this week.

"I promise you if I'm elected president, you're going to see the single most important thing that changes America," Biden announced. "We're gonna cure cancer."

The crowd cheered in response. But Biden's promise made one cancer expert cringe.

"Are we going to open the news one day and hear that cancer has been cured? No," Deanna Attai, an assistant clinical professor of surgery at the University of California Los Angeles, told Live Science. "It's just not that simple," she added. This campaign promise is misleading because it suggests that cancer is one disease with one cure, which is not the case, Attai said.

More than one disease, more than one cure

There are more than 100 kinds of cancer, according to the National Institutes of Health. Each of those cancers has a different cause, from viruses to radiation. Each demands its own treatment. Developing individual treatments for each variety of cancer — from screening tools to therapies — is a piecemeal process. "It's two steps forward, one step back," Attai said.

So when Biden promises to cure cancer, he's talking about curing not just one, but many diseases. Some of those diseases, we may realistically never be able to cure. After all, cancer is characterized by cells that "take on a life of their own," she added. These cells can mutate, change and evade the drugs scientists develop.

So a single cure for all cancers? That's not going to happen, Attai said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even a single, incredibly effective cancer drug takes much more than a presidential term to develop. Before they become available to patients, treatments must go through years of animal testing and clinical trials. The whole process can take years, often longer than a single presidential term, Attai said.

Not the only way to save lives

There's another issue with the promise of a singular cure for cancer: it isn't the only way to save people from cancer. And since cancer research funding isn’t unlimited, focusing only on a cure can potentially mean spending less money on other avenues that could save just as many lives.

Since 1991, cancer death rates have dropped by 27%— 2,629,200 fewer deaths than we would have expected, according to the American Cancer Society. The main reason for this progress? People smoke less. Lung cancer, one of the top three deadliest forms of cancer, has seen some of the steepest declines over the past three decades.

Although not all cases of cancer prevention are as cut and dry as reducing smoking, many cases of cancer are likely preventable through reducing environmental harm. Other potential causes of cancer include obesity, a sedentary lifestyle and exposure to air pollution.

"Focusing on a cure doesn't address why cancer is developing in the first place," Attai said.

It also doesn't address socioeconomic disparities and the resulting gulf in access to care, she added. Overall, cancer deaths are 20% higher in the country's poorest communities compared to the richest communities, due in part to discrepancies in health care access, according to a report by the American Cancer Society. The greatest differences in cancer outcomes between these communities occur in the most preventable and treatable cancers, the report adds. For example, we know that a vaccine can prevent most cases of cervical cancer, which is the second deadliest cancer in women ages 20 to 39, according to the American Cancer Society. Twice as many women die from this cancer in lower income counties compared to the highest income counties. By eliminating this gap in access to treatment, one study estimated that 34% of these deaths could be prevented.

A cure for all cancers may not be a realistic campaign promise — but there are steps that can be taken toward reducing cancer's impact, Attai said. Those steps include funneling dollars into research, programs that provide health care to underserved communities and public health spending.

"Progress in treating cancer is incremental," Attai said, "We shouldn't be putting an artificial timeline on a cure."

Originally published on Live Science.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus