Why'd I Come in Here? A Brain Zap Could Boost That Fuzzy Memory

Fuzzy memories can be frustrating, whether you're at the grocery store trying to recall if you finished the last bit of milk or in court giving eye-witness testimony.

Now, a new study finds that zapping the brain might boost that memory. After receiving stimulation in a certain part of the brain, study participants were 15.4% better at recalling memories, a group of researchers reported on May 6 in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience.

Specifically, these subjects were better at recalling episodic memories, those that involve a specific time and a place. "In an episodic memory, you have contextual detail," said senior author Jesse Rissman, an assistant professor of psychology and of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles. [6 Fun Ways to Sharpen Your Memory]

Rissman and his team recruited 72 people for two consecutive days of testing. On the first day, the participants were shown 80 different words and asked to remember them in context. For example, if one of the words was "cake," the participants were asked to imagine themselves or someone else interacting with the cake. (Remembering the word "cake" isn't an episodic memory, but remembering that you ate cake yesterday on the balcony is.)

The next day, the participants took tests to measure their memory, reasoning and perception; in these evaluations, they were asked to recall if they saw certain words the day before and to organize those words into categories, among other tasks.

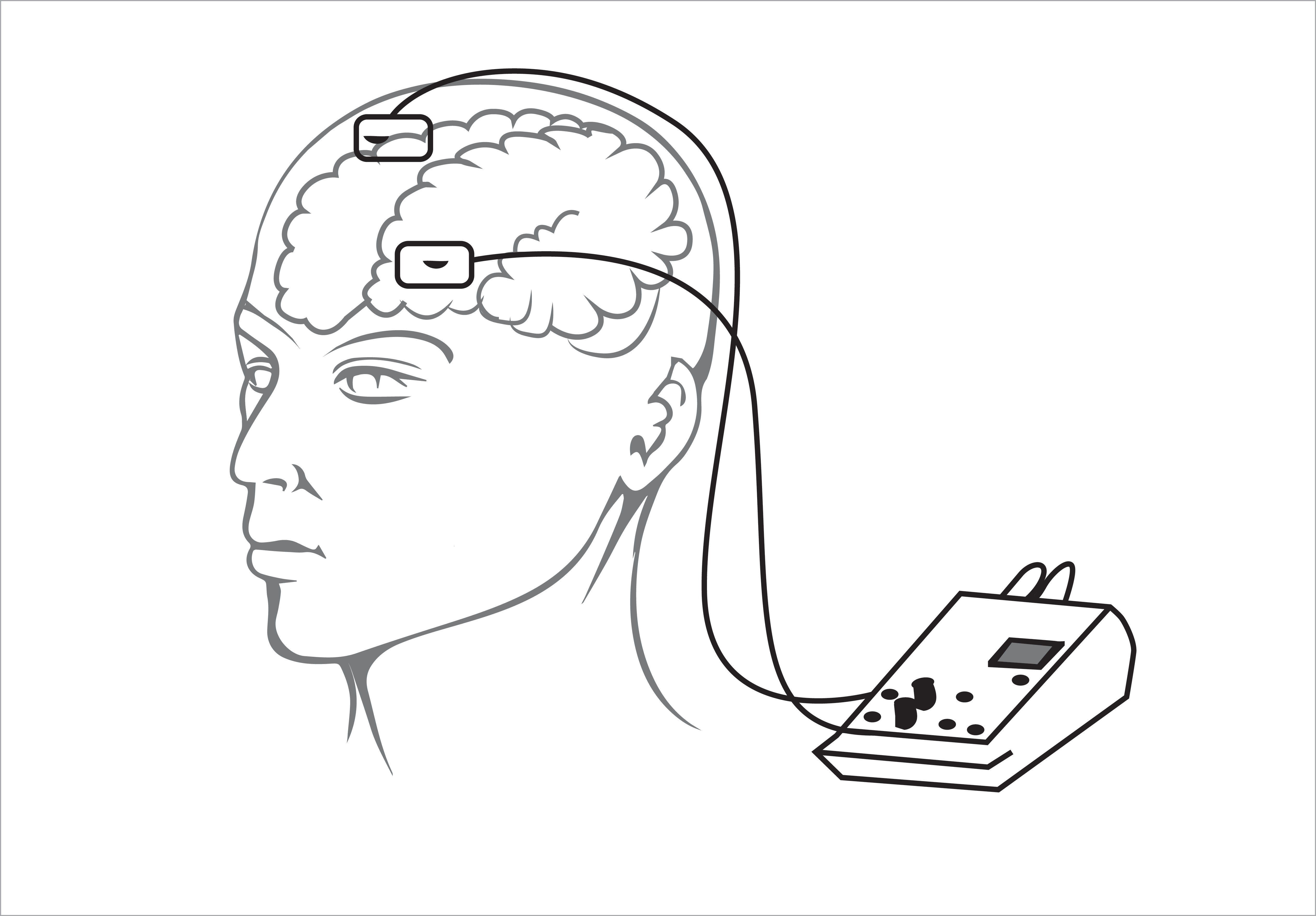

All the while, they were hooked up to two electrodes and a 9-volt battery, which zapped their brains for less than a minute. The rest of the time, there was no zapping. The setup, called a sham stimulation, was meant to suggest to the participants they were being zapped the whole time and just got used to the stimulation. (Although after the study most participants reported they could tell more or less when they received zaps)

Then, the participants were split into three groups: The first received additional brain zaps to increase the activity of a specific part of the prefrontal cortex known to be important in episodic memory recollection; the second group received a "backward" current (done by switching the polarities of the electrodes), which previous research has suggested either decreases activity of the brain cells or doesn't do anything; the third group continued to receive sham stimulations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though the participants didn't show any improvement in reasoning or perception after receiving the zaps, the people who received the actual currents had a 15.4% higher score on their memory tests than they did before being zapped. The researchers didn't see any significant improvements in the groups receiving the backward current or the sham stimulations.

But a limitation of the study is that, though the zaps were aimed at a very specific region of the brain, the researchers couldn't be sure the pulses weren't also affecting other regions.

Rissman said this is the first time that a study has tested what happens if an electrical stimulation is applied as a person tries to recall a memory. But otherwise, zapping the brain to improve memory isn't new.

Last year, for example, research funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) found that zapping the brain of a sleeping person could boost a different kind of memory, called "generalization" memory.

But brain-zapping studies, including the new one, are at a very preliminary stage. "It's a narrow scenario to have in real life," and it is not going to be very practical unless you have people walking around with this apparatus strapped to their heads, Rissman said.

"While these initial results are very encouraging, we want to do more experiments to understand how consistent this benefit is," he said. But researchers also want "to have a better handle on what types of memories are most amenable" to this type of brain zapping.

- 5 Ways to Beef Up Your Brain

- Why You Forget: 5 Strange Facts About Memory

- Mind Games: 7 Reasons You Should Meditate

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus